See 490212

Author Archives: Swany

cabbage to the vine

Among the examples of pairings whose antipathies are not as vehement as the hatred thieves have of a certain usage of Pantagruelion.

Notes

cabbage

vino adversari ut inimicam vitibus, antecedente in cibis caveri ebrietatem, postea sumpta crapulam discuti.

As cabbage is the enemy of the vine, they say that it opposes wine; that if taken in food beforehand it prevents drunkenness, taken after drinking it dispels its unpleasant effects.

cabbage

Olus caulesque,quibus nunc principatus hortorum, apud Graecos in honore fuisse non reperio, sed Cato brassicae miras canit laudes, quas in medicinae loco reddemus.

Cabbages and kales which now have preeminence in gardens, I do not find to have been held in honour among the Greeks; but Cato [R.R. CLVI. f.] sings marvellous praises of the head of cabbage, which we shall repeat when we deal with medicine.

cabbage

[Cato does sing the praises of cabbage, but he does not mention that it is inimical to the vine.]

cabbage

Silvestris sive erraticae inmenso plus effectus laudat Cato, adeo ut aridae quoque farinam in olfactorio collectam, vel odore tantum naribus rapto, vitia earum graveolentiamque sanare adfirmet. hanc alii petraeam vocant, inimicissimam vino, quam praecipue vitis fugiat aut, si non possit fugere, moriatur

Cato gives vastly higher praise to the wild, or stray, cabbage, so much so that he asserts that the mere powder of the dried vegetable, collected in a smelling-bottle, or the scent only, snuffed up the nostrils, removes nose-troubles and any offensive odour. Some call this variety rock-cabbage; it is strongly antipathetic to wine, so that the vine tries very hard to avoid it, or, if it cannot do so, dies.

cabbage

Brassicae laudes longum est exsequi, cum et Chrysippus medicus privatim volumen ei dicaverit per singula membra hominis digestum, et Dieuches, ante omnes autem Pythagoras, et Cato non parcius celebraverit, cuius sententiam vel eo diligentius persequi par est, ut noscatur qua medicina usus sit annis dc Romanus populus.

It would be a long task to make a list of all the praises of the cabbage, since not only did Chrysippus the physician devote to it a special volume, divided according to its effects on the various parts of the body, but Dieuches also, and Pythagoras above all, and Catob no less lavishly, have celebrated its virtues;

le Chou, a la Vigne:

pernicialia et brassicae cum vite odia, ipsum olus quo vitis fugatur adversum cyclamino et origano arescit.

Deadly too is the hatred between the cabbage and the vine; the very vegetable that keeps the vine at a distance itself withers away when planted opposite cyclamen or wild marjoram.

cabbage

Morbos hortensia quoque sentiunt sicut reliqua terra sata. namque et ocimum senectute degenerat in serpyllum, et sisymbrium in zmintham, et ex semine brassicae vetere rapa fiunt, atque invicem.

Garden vegetables are also liable to disease, like the rest of the plants on earth. For instance basil degenerates with old age into wild-thyme and sisymbrium into mint, and old cabbage seed produces turnip, and so on.

Le chou à la vigne

Voiez Pline, l. 17. chap. 24 & l. 24. chap. 1.

Cabbage to the Vine

Pliny xxiv. 1, § 1.

Le chou à la vigne

«Pernicialia et brassicæ cum vite odia: ipsum olus quo vitis fugatur, adversum cyclamino… arescit», dit Pline, XXIV, I. «Le chou, disent Ch. Estienne et J. Liébault, ne doit estre planté prés la vigne, ny la vigne prés du chou: car il y a si grand inimitié entre ces deux plantes que les deux plantes en un mesme terroir ayant prins quelque croissance se retournent arrière l’un de l’autre et n’en sont tant fructueuses.» (L’agriculture et maison rustique, nouvelle éd., Rouen, Laudet, 1625, in-4°, l. II. p. 155.) Cette assertion est d’ailleurs d’origine légendaire: d’après une tradition transmise par le scoliaste d’Aristophane (Les Chevaliers), Lycurgue, roi de Thrace, ayant fait détruire les vignes, un cep qu’il allait trancher l’ença tout à coup de ses sarments. Devinant la vengeance de Bacchus, le barbare se mit à pleurer; de ses larmes naquit le chou, remède traditionnel, préventif et curatif de l’ivresse. (Paul Delaunay)

cabbage to vines

(did not Lycurgus, King of Thrace, destroy the vines, when suddenly a stalk cast its twigs about him, and when from his tears, shed at Bacchus’ vengeance, was born the colewort, a traditional preventive and cure for drunkenness)

Nenuphar…

Encore une fois, la plupart de ces exemples se retrouvent dans le De latinis nominibus de Charles Estienne. Le nenufar et la semence de saule sont des antiaphrodisiaques. La ferula servait, dans l’Antiquité, à fustiger les écoliers (cf. Martial, X, 62-10).

vine

vine. Forms: vygne, vigne, vinyhe, vyny. vyne, vyn, viyn, vine, vijne; wine, wyne, vinde, vynde. [adopted from Old French vigne and vine (modern French vigne): -Latin vinea vineyard, vine, etc., formed on vin-um wine.]

The trailing or climbing plant, Vitis vini-fera, bearing the grapes from which ordinary wine is made (= grape-vine); also generally, any plant of the genus Vitis.

13.. King Alisander 5758 (Laud. MS.), In eueryche felde rype is corne; Þe grapes hongen on þe vyne.

1377 William Langland The vision of William concerning Piers Plowman xiv. 30 Þough neuere greyne growed ne grape vppon vyne.

C. 1420 Palladius on husbondrie vi. 57 Now vyne and tre that were ablaqueate, To couer hem it is conuenient.

1535 Miles Coverdale Bible Judges ix. 12 Then sayde the trees vnto the vyne; Come thou and be oure kinge.

1562 William Turner A new herball, the seconde parte ii. 168 b, [It] is lyke vnto a gumme, and waxeth thicke aboute the bodye of the vinde.

1573 Thomas Tusser Fiue hundreth pointes of good husbandrie (1878) 75 Get doong, friend mine, for stock and vine.

1598 Joshuah Sylvester, translator Du Bartas his divine weekes and workes i. iii. 586 There, th’ amorous Vine calls in a thousand sorts (With winding arms) her Spouse that her supports.

1708 John Philips Cyder i. 16 Everlasting Hate The Vine to Ivy bears.

A single plant or tree of this species or genus.

A. 1300 E.E. Psalter civ. 31 He… smate þar vinyhes and figetres in-twa.

1303 Robert Manning of Brunne Handlyng Synne 882 Euery 3ere at þe florysyngge, whan þe vynys shulde spryngge, A tempest… fordede here vynys alle.

1340 Dan Michel’s Ayenbite of Inwyt 43 Þe zenne of ham þet uor wynnynge… destrueþ þe vines oþer cornes.

1340-70 Alexander and Dindimus. 847 Ze telle vs þat 3e tende nauht to tulye þe erþe,… no plaunte winus.

1390 John Gower Confessio amantis II. 168 For he fond… how men scholden sette vines.

1422 James Yonge, translator. The gouernaunce of prynces (in Secreta Secretorum) 244 In al regions the hettes bene encreschid,… the wynes growyth, the cornes wixit rippe.

C. 1440 Promptorium parvulorum sive clericorum 510/2 Vyny, þat bryngythe forþe grete grapys, bumasta.

1590 Edmund Spenser The Færie Queene ii. xii. 54 A Porch with rare deuice, Archt ouer head with an embracing vine.

1604 Edward Grimstone, translator D’Acosta’s Naturall and morall historie of the East and West Indies iv. xxxii. 296 Peru and… Chillé, where there are vignes that yeeld excellent wine.

peaches

Among the plants that have retained the names of the regions from which they were formerly transported.

Notes

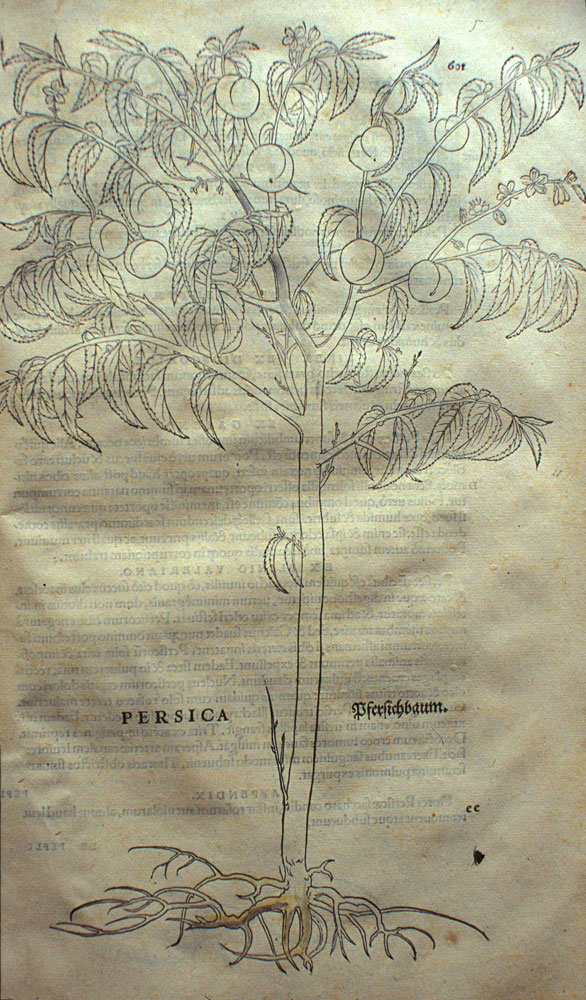

persica

Persica

Pfersichbaum

Taxon: Prunus persica (L.) Batsch

Ancient Greek: persika mela

English: peach

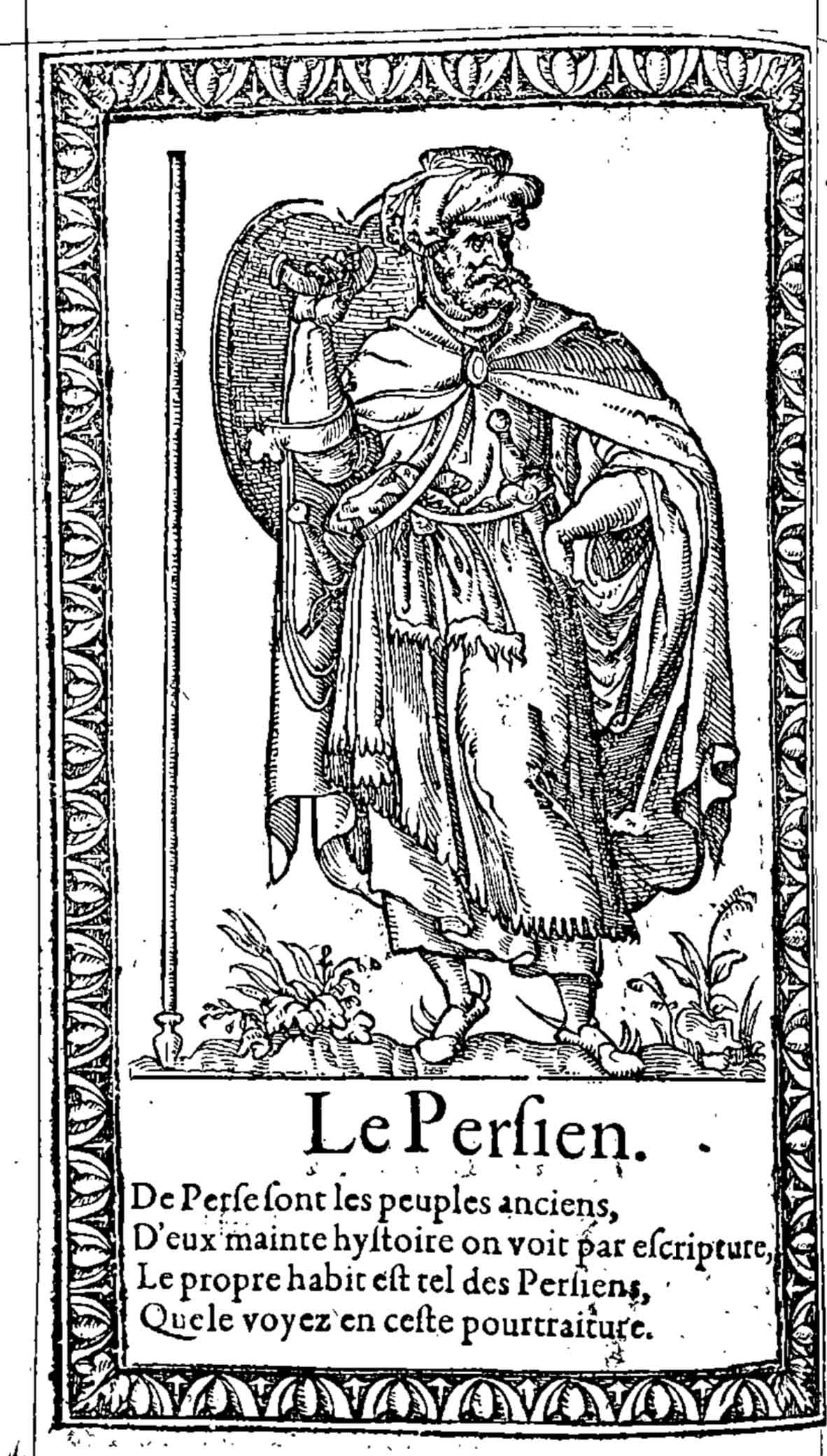

Le Persien

De Perse sont les peuples anciens,

D’eux mainte hystoire on voit par escripture,

Le propre habit est tel des Persiens,

Que le voyez en cest pourtraiture.

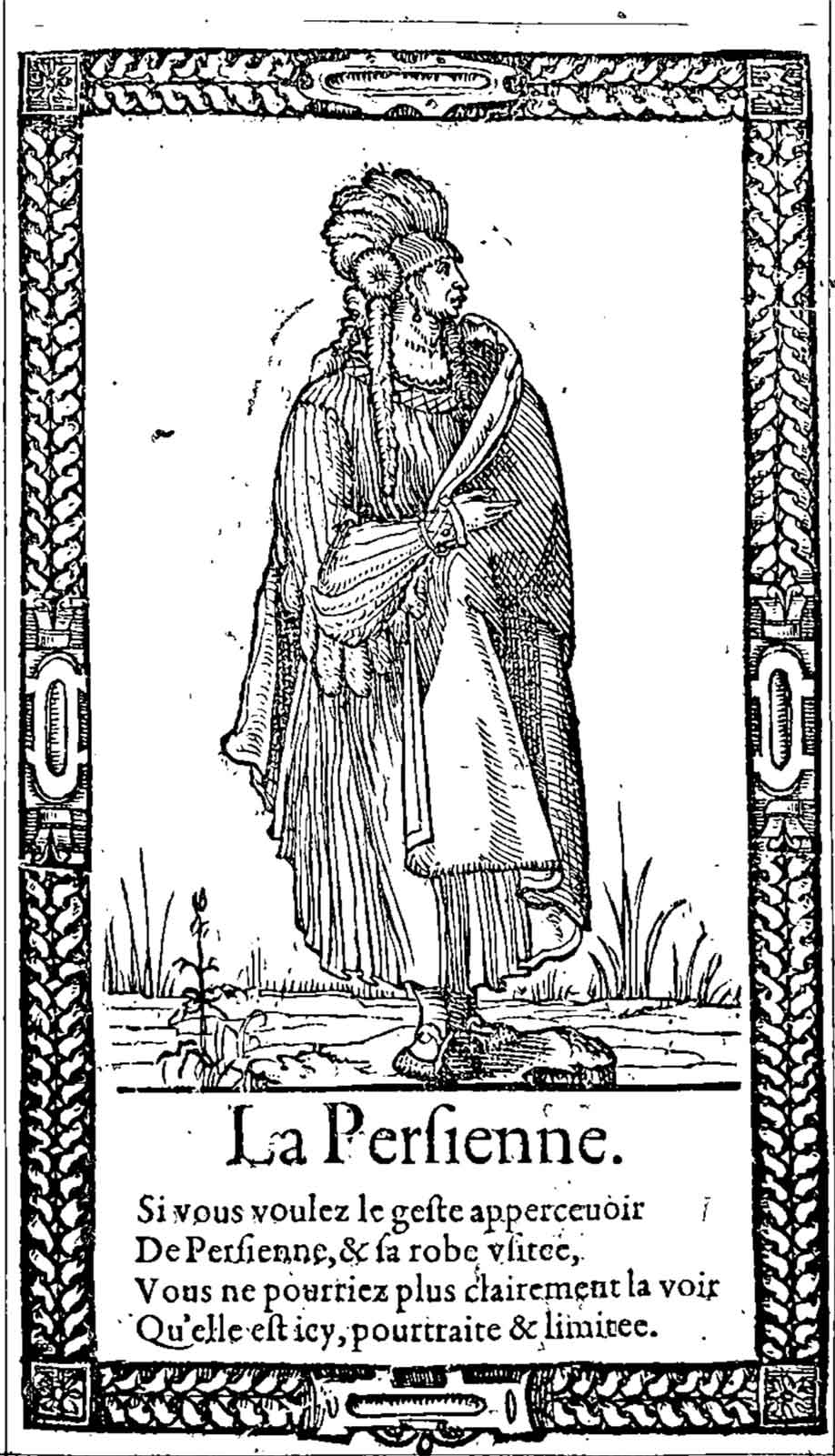

La Persienne

Si vous voulez le geste appercevoir

De Persienne, & sa robe usitee,

Vous ne pourriez plus clairement la voir

Qu’elle est ici, pourtraite & limitee.

persica

In totum quidem Persica peregrina etiam Asiae Graeciaeque esse ex nomine ipso apparet, atque ex Perside advecta. sed pruna silvestria ubique nasci certum est, quo magis miror huius pomi mentionem a Catone non habitam, praesertim cum condenda demonstraret quaedam et silvestria. nam Persicae arbores sero et cum difficultate transiere, ut quae in Rhodo nihil ferant, quod primum ab Aegypto earum fuerat hospitium. falsum est venenata cum cruciatu in Persis gigni et poenarum causa ab regibus translata in Aegyptum terra mitigata; id enim de persea diligentiores tradunt, quae in totum alia est myxis rubentibus similis nec extra orientem nasci voluit. eam quoque eruditiores negaverunt ex Perside propter supplicia translatam, sed a Perseo Memphi satam, et ob id Alexandrum illa coronari victores ibi instituisse in honorem atavi sui. semper autem folia habet et poma subnascentibus aliis. sed pruna quoque omnia post Catonem coepisse manifestum erit.

The Persian plum or peach, it is true, is shown by its very name to be an exotic even in Asia Minor and in Greece, and to have been introduced from Persia. But the wild plum is known to grow everywhere, which makes it more surprising that this fruit is not mentioned by Cato, especially as he pointed out the way of storing some wild fruits also. As for the peach-tree, it was only introduced lately, and that with difficulty, inasmuch as in Rhodes, which was its first place of sojourn after leaving Egypt, it does not bear at all. It is not true that the peach grown in Persia is poisonous and causes torturing pain, and that, when it had been transplanted into Egypt by the kings to use as a punishment, the nature of the soil caused it to lose its dangerous properties; for the more careful writers relate this of the persea [The persea is the modern Mimusops Schimperi, and the myxa is the modern sebesten], which is an entirely different tree, resembling the red myxa, and which has refused to grow anywhere but in the east. The sebesten also, according to the more learned authorities, was not introduced from Persia for punitive purposes, but was planted at Memphis by Perseus, and it was for that reason that Alexander, in order to do honour to his ancestor, established the custom of using wreaths of it for crowning victors in the games [Instituted by Alexander in honour of the hero Perseus, son of Zeus, from whom he claimed descent] at Memphis. It always has leaves and fruit upon it, fresh ones sprouting immediately after the others. But it will be obvious that all our plums also have been introduced since the time of Cato.

Persicques

Urquhart translates as “Persicarie.” Ozell notes, “Rabelais says, Persique (Persica), a Peach-tree, not the herb called Persicaria, i.e. Arse smart or Cul-rage.”

Peaches

“Persica mala; ex Perside advecta” (Pliny xv. 13, § 13).

persicques

« Ex Perside advecta [persica] », dit Pline (XV, 13). C’est le pècher, Persica vulgaris, D. C. Les Grecs et les Romains le reçurent de la Perse ou de l’Asie orientale, mais de Candolle le croit originaire de la Chine. (Paul Delaunay)

Persia

Persian. Forms: Percien, -sien, -cynne, -syn, -sen; -san, -sante, Persian, ( -cian). [originally Middle English Persien, adopted from French persien: -Latin type *Persianus, formed on Persia, name of the country, in Greek Persij.]

Of or pertaining to Persia (modern Iran), or its inhabitants or language. Also, of or pertaining to a Persian cat.

A. 1400-50 Alliterative Romance of Alexander 2885 Þe pure propure name in percynne tonge.

1587 Harrison England ii. xxii. (1877) I. 338 Our men are… become..through Persian delicacie crept in among vs altogither of straw.

1605 Shakespeare King Lear iii. vi. 85, I do not like the fashion of your garments. You will say they are Persian.

Fragment 500442

similarly Lyncus king of Scythia

Original French: pareillement Lyncus roy de Scythie

Modern French: pareillement Lyncus roy de Scythie

Lyncus

Pour lynx, par le retranchement de l’l initiale, comme si c’étoit l’article le contracté avec le nom. Nous avons déja trouvé cette leçon plus haut.

Œuvres de Rabelais (Edition Variorum)

Charles Esmangart [1736-1793], editor

Paris: Chez Dalibon, 1823

Google Books

Lyncus

Sur Lyncus, Rabelais traduit Servius commentant l’Énéid, I, 323.

Le Tiers Livre

Jean Céard, editor

Librarie Général Français, 1995

Scythian

Scythian. Also 6-7 Sythian. [formed on Latin Scythia, adopted from Greek Skuqi´a]

Pertaining to Scythia, an ancient region extending over a large part of European and Asiatic Russia, or to the nomadic people by whom it was inhabited.

1567 Golding Ovid’s Metamorphoses xv. 312 Hypanis That springeth in the Scythian hilles.

1587-90 Marlowe 1st Pt. Tamburl. i. i. 44 Tamburlaine, that sturdie Scythian thiefe.

1596 Spenser State Irel. Wks, (Globe) 630/1 For though it [Nomadism] be an old Scythian use, yet it is very behoofull in that countrey of Ireland.

A. 1625 Beaum. & Fl. Four Plays in One, Tri. Death vi, What Scythian snow so white? what crystal chaster?

1776 Mickle tr. Camoens’ Lusiad Introd. 14 The irruptions of northern or Scythian barbarians.

of the nature of Vervain

Notes

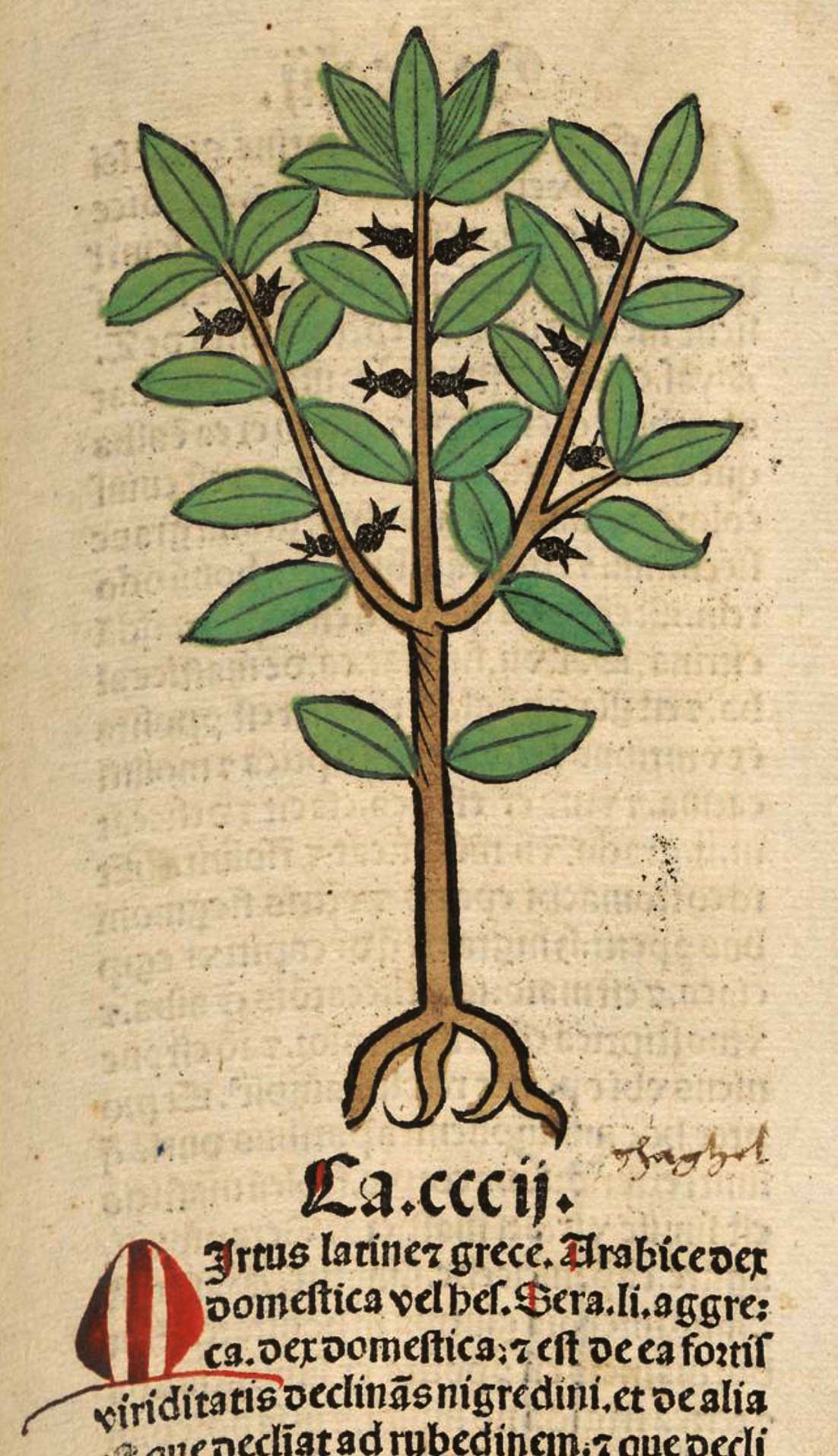

Mirtus

Verbenaca supina

Verbenaca supina sive foemina

Eisenkraut weible

Verbena officinalis L.

English: vervain

French: verveine officinale

German:Eisenkraut

Verbenaca

verbenaca

Verbena officinalis L

vervain

alii fontemque ignemque ferebant

velati limo et verbena tempora vincti.

Rutulians and Teucrians had measured the field for the combat under the great city’s walls, and in the middle were preparing hearths and grassy altars to their common deities. Others were bringing fountain water and fire, draped in aprons and their brows bound with vervain.

verbenique

De la nature de la vervenne, anciennement en usage dans les operations magiques.

verbenicque

De la nature de las verveine, anciennement en usage dans les opératons magiques.

verbenicque

Semblable à vervaine, magique.

Vervain

Vervain (Lat. vervena), a kind of holy twigs or branches, such as myrtle, laurel, etc., which were carried or worn by the Roman Fetials, etc., on solemn or festive occasions. For most of this cf. Pliny xix §§ 2-6.

verbenicque

Ιερἀ βοτάνη, Diosc., IV, 61; verbenaca, hierabotane, peristereon, Pline XXV, 59. La verveine est une des trente-six herbes magiques énumérées au Livre Sacré d’Hermès Trismégiste; c’était également une plante sacrée chez les Gaulois; les Druides nettoyaient leurs autels avec de petits balais de verveine. La religion romaine en faisait aussi usage, au dire de Pline, et les magiciens l’employaient dans une foule de pratiques. La verveine des Anciens peut se rapporter: la mâle, à notre Verbena officinalis, L., la femelle à notre V. supina, L. Cf. J.-B. L. Bejottes, Le livre sacré d’Hermès Trismégiste et ses trente-six herbes magiques, 1911; et G. Hubert, Des Verbénacées utilisées en matiére médicale, Lechevrel, 1921. (Paul Delaunay)

herbe sacre

Cf. Virgile, Enéid, XII, 120, « Velati lino, et verbena tempora vincti » ; Servius, qui lit limo pour lino, commente ainsi le mot verbena : « Verbenas vocamus omnes frondes sacratas, ut set laurus, oliva et myrtus ».

Verbenicque

La verveine était dans l’Antiquité une plante sacrée.

verbenicque

La verveine (verbena) était, pour les Anciens, une plante sacrée. Les âmes des morts exigent que leurs corps soient ensevelis dans des linceuls de pantagruélion.

vervain

vervain. Forms: verueyn(e, -veyn(e, -ueine, verveine, vervein, vervaine, wayne (warwayn), -uaine, vervain, veruen(e -ven. [adopted from Anglo-French and Old French verveine (13th century; Old French also vervainne, modern French verveine), adaptation of Latin verbena verbena.]

The common European and British herbaceous plant, Verbena officinalis, formerly much valued for its reputed medicinal properties. Also rarely, some other species of the genus Verbena, or the genus itself.

1390 John Gower Confessio amantis II. 262 Tok sche fieldwode and verveyne, Of herbes ben noght betre tueine.

C. 1400 Lanfranc’s Science of cirurgie 243 A 3elke of an eij, & as miche of oile of rosis, & as miche of iuys of verueine.

A. 1400 Stockholm Med. MS. ii. 315 in Anglia XVIII. 315 A lytyll wyl I tellyn of verwayne, Herbe þat meche is of mayne.

A. 1425 translation Arderne’s Treatise of fistula inano Fistula, etc. 64 Vitriol… made with Iuyse of moleyn, or of plantayne, or verueyn.

1611 Randle Cotgrave, A dictionarie of the French and English tongues, Verveine, Verueine, Holie hearbe, Iunoes teares.

1533 Sir Thomas Elyot The castel of helth (1541) 9 b, Thynges good for the eyes: Eyebryght: Fenell: Vervyn.

1548 William Turner The names of herbes in Greke, Latin, Englische, Duche, and Frenche ii. 162 The second kinde of Veruine… . The leaues of thys… are good agaynst… serpentes.

1567 John Maplet A green forest or a naturall historie, wherein may be seen … the most sufferaigne vertues in all … stones and mettals … plantes, herbes … brute beastes etc. 64 Veruen, of some after their language is called Holy Herbe.

1591 Thomas Lodge Hist. Dk. Normandy B ij b, Thou art like the veruen,… poyson one wayes, and pleasure an other.

1596 Thomas Cogan The hauen of health xxi. 41 Also one olde saying I haue heard of this herbe, That whosoeuer weareth Veruin and Dill, May be bold to sleepe on euery hill.

1597 John Gerard (or Gerarde) The herball, or general historie of plants ii. ccxxxv. 580 There be two kindes of Veruaine as Pliny saith, the male, and the female; or as others affirme, vpright, and creeping.

1671 William Salmon Synopsis medicinæ iii. xxii. 439 Vervain… is good against Tertian and Quartan Agues.

1782 J. Scott Poet. Wks. 97 Vervain blue for magic rites renown’d.

1830 Lindley Nat. Syst. In botany 239 The properties formerly ascribed to the Vervain appear to have been imaginary.

the Pastaphores clad

the Pastaphores clad,

Original French: les Paſtophores reueſtuz,

Modern French: les Pastophores revestuz,

Notes

prétes d’Isis vetus de lin

ergo hic praecipuum summumque meretur honorem

qui grege linigero circumdatus et grege calvo

plangentis populi currit derisor Anubis.

Consequently, the highest, most exceptional honour is awarded to Anubis, who runs along, mocking the wailing populace, surrounded by his creatures in linen garments and with shaved heads.

[Anubis, the dog-headed god and guardian of Isis. Here a priest dressed as Anubis mocks the people for their lamentation over the “death” of Osiris, the consort of Isis.]

Certains Pastaphores

Vous leurs favorisez (dist Iuppiter) à ce que ie voy bel messer Priapus. Ainsi n’estes à tous favorable. Car veu que tant ilz couvoient perpetuer leur nom & memoire, ce seroit bien leur meilleur estre ainsi après leur vie en pierres dures & marbrines convertiz, que retourner en terre & pourriture. Icy darrière vers ceste mer Tyrrhene & lieux circumvoisins de l’Appennin voyez vo’ quelles tragedies sont excitées par certains Pastophores.

Tiers Livre Chapter 48

Comment Gargantua remonstre n’estre licite es enfans soy marier, sans le sceu et adveu de leurs peres & meres. Chapitre XLVIII

[…]

Filz trescher (dist Gargantua) je vous en croy, & loue Dieu de ce que a vostre notice ne viennent que choses bonnes & louables, & que par les fenestres de vos sens rien n’est on domicile de vostre esprit entré fors liberal sçavoir. Car de mon temps a esté par le continent trouvé pays on quel ne sçay quelz pastophores Taulpetiers autant abhorrens de nopces, comme les pontifes de Cybele en Phrygie, si chappons feussent, & non galls pleins de salacité & lascivie: les quelz ont dict loix es gens mariez sus le faict de mariage.

Tiers Livre Chapter 48

How Gargantua sheweth that it is not lawful for Children to marry without the Knowledge and Consent of their Fathers and Mothers. Chapter XLVIII.

[…]

“My very dear Son,” quoth Gargantua, “I believe you in this, and praise God in that only such things come into your Thoughts as are good and praiseworthy, and that by the Windows of your Senses nothing has entered into the Dwelling-place of your Mind save liberal Knowledge. For in my time on the Continent hath been found a Country, in which are certain pastophorian Molecatchers, as far removed from Marriage as the Priests of Cybele in Phrygia, if only they had been Capons and not Cocks full of Wantonness and Lasciviousness, who have dictated Laws to married Folk in the matter of Marriage.

Pastophores

Translated by Urquhart as “the pastophorian priests.” Ozell notes, “Only Pastophores in French. The were the pontiffs among the Egyptians, in the temple of Serapis. [greek] “pallidum sacerdotale, a cope. Pallium Veneris quod ferebant in Egypto sacerdotes cæteris honoratiores.” The place of their abode was close to the temple, and called the Pastophorium. Ruff. Eccles Hist l. ii. c. xxiii. ‘Item Hieron. in Esa. pastopho.ium, inquit, est thalamus, in que habitat præpositus templi.’”

Pastophores

Les Egyptiens firent de grands efforts poir remédier aux inconvéniens de leir façon d’écrire: leur ordre sacerdotal était partagé, sans doute dès long-temps, en deux castes dont l’une obéissait à l’autre; ils le subdivisèrent encore. La première caste forma les quatre classes, des propètes, des hiérostolites, des hiérogrammates et des horoscopairesl la seconde fut divisée en pastaphores et en néocores chacune d’elles se livra spécialement à un genre de travaux.

Pastophores

Terme d’archæologie. Prêtes qui portaient le lit de Vénus dans certaines cérémonies. Ils pratiquaient la médecine en Egypte. — Autres prêtes chargés de lever le voile qui, à la porte des tempoles égyptiens, cachait la divinité. (Du grec pastas lit ou pastos voile, et phêrd je porte.

pastophores

Ch. 48, n. 4. Chez les Egyptiens, les pastaphores (παστόψοροζ, Diodore de Sicile, I, 29) étaient des prêtes chargés de porter les statues des dieux dans les chapelles du temple. Avant R., Budé avait employé ce mot au sens général de prêtes. Cf Sainéan, t. I, p. 8 et t. II, p. 53.

pastaphores

pour les pastaphores, voir XLVIII, p. 497 et n. 2.

Isiacques and Pastaphores

Les prêtes d’Isis étaient vêtus de lin; Juvénal, Satires, VI, 532, les appelle «grex liniger»; voir aussi Ovide, Métamorphoses, I, 767. Les pastophores portaient dans les châsses les images des dieux : ils représent les prêtes, revêtus de l’aube.

pastophor

pastophor, pastophorus. [adopted from French pastophore, adaptation of Latin pastophorus, adopted from Greek pastoforoj, formed on pastoj a shrine, +roj carrying. More usually in Latin form.]

One of the order of priests who carried shrines of the gods in procession, as frequently represented in Egyptian art.

1658 Phillips, Pastophories, (Greek) the most honourable order of Priests among the Egyptians.

1706 Phillips (ed. Kersey), Pastophori, certain Priests, whose Business it was, at solemn Festivals, to carry the Shrine of the Deity.

1891 translation De La Saussaye’s History of Scotch Relig. l. 437 Singers, pastophores, hierodules and others.

aconite, to leopards and wolves

aconite, to leopards and wolves;

Original French: le Aconite, aux Pards & Loups:

Modern French: le Aconite, aux Pards & Loups:

Among the examples of pairings whose antipathies are not as vehement as the hatred thieves have of a certain usage of Pantagruelion.

Notes

Pardus (leopard)

144. Pardus (leopard)

Fol. 30rb1: column miniature

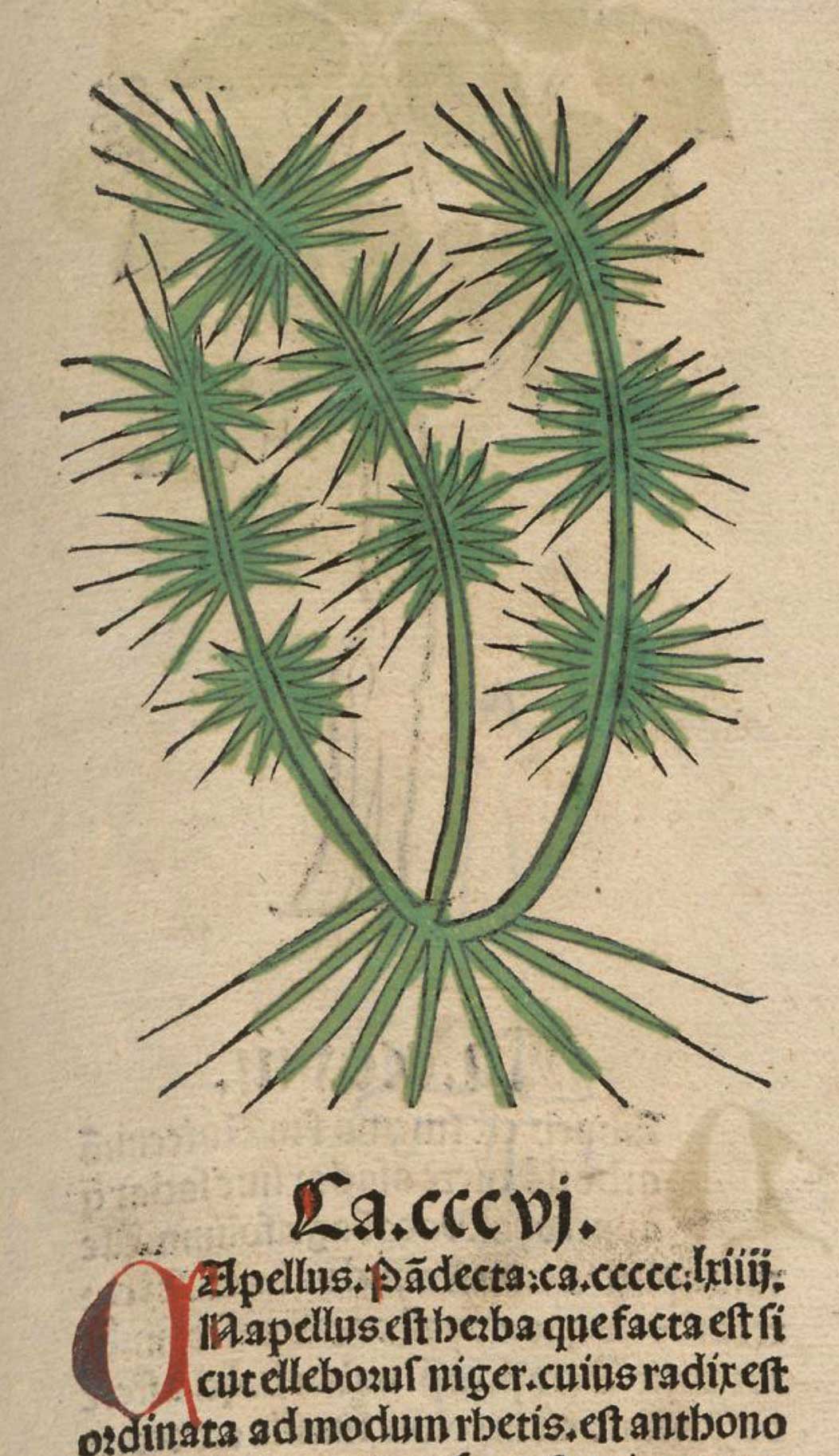

Napellus

Aconitum

Aconitum lycoctonon

Wolffswurtz

Aconitum vulparia Reichenb.

Ancient Greek:akoniton eteron

English: Badgersbane, Wolfsbane, Wolfsbane monkshood

French: Etrangle-loup, Herbe au loup, Tue-loup, Aconit étrangle-loup

German: Wolfseisenhut

Lupus

aconite

Wolf’s-bane grows in Crete and in Zakynthos, but is most abundant and best at Herakleia in Pontus. It has a leaf like chicory, a root like in shape and colour to a prawn,3 and in this root resides its deadly property, whereas they say that the leaf and the fruit produce no effects. The fruit is that of a herb,4 not that of a shrub or tree. It is a low-growing herb and shows no special feature, but is like corn, except that the seed is not in an ear. It grows everywhere and not only at Akonai,1 from whence it gets its name (this is a village of the Mariandynoi): and it specially likes rocky ground. Neither sheep nor any other animals eat it.

1. Plin. 6. 4, Portus A cone veneno aconito dirus. But in 27. 10. he apparently did not recognise Ἀκόναις as a proper name, and translates it in nudis cautibus, misled perhaps by πετρώδεις τόπους below.

Wolf’s bane

9.18.2 Wolf’s bane,1 which some call ‘scorpion-plant’ because it has a root like a scorpion, kills that animal if it is shredded over him; while if one then sprinkles him with white hellebore, they say that he comes to life again. It is also fatal to oxen sheep beasts of burden and in general to any fourfooted animal, and kills them the same day if the root or leaf is put on the genitals; and it is also useful as a draught against a scorpion’s sting.

1. Referred to by Ael. H. A. 9. 27; Apollon. Hist. Mirab. 41. cf. Plin. 25. 122 (cf. 27. 6); Diosc. 4. 76. This is evidently a different plant to the σκορπίος mentioned 9. 13. 6. See Index.

Aconite, aux Pards & Loups

pantheras perfricata carne1 aconito [venenum id est] barbari venantur; occupat ilico fauces earum angor (quare pardalianches id venenum appellavere quidam), at fera contra hoc excrementis hominis sibi medetur, et alias tam avida eorum ut a pastoribus ex industria in aliquo vase suspensa altius quam ut queat saltu attingere iaculando se appetendoque deficiat et postremo expiret, alioqui vivacitatis adeo lentae ut eiectis interaneis diu pugnet.

Barbarian hunters catch leopards by means of meat rubbed over with wolf’s-bane; their throats are at once attacked by violent pain (in consequence of which some people have given this poison a Greek name meaning choke-leopard), but to cure this the creature doses itself with human excrement, and in general it is so greedy for this that shepherds have a plan of hanging up some of it in a vessel too high for the leopard to be able to reach it by jumping up, and the animal keeps springing up and trying to get it till it is exhausted and finally dies, although otherwise its vitality is so persistent that it will go on fighting for a long time after its entrails have been torn out.

Aconite, aux Pards & Loups

Sed antiquorum curam diligentiamque quis possit satis venerari? constat omnium venenorum ocissimum esse aconitum et tactis quoque genitalibus feminini sexus animalium eodem die inferre mortem. hoc fuit venenum quo interemptas dormientes a Calpurnio Bestia uxores M. Caelius accusator obiecit. hinc illa atrox peroratio eius in digitum. ortum fabulae narravere e spumis Cerberi canis extrahente ab inferis Hercule ideoque apud Heracleam Ponticam, ubi monstratur is ad inferos aditus, gigni. hoc quoque tamen in usus humanae salutis vertere scorpionum ictibus adversari experiendo datum in vino calido. ea est natura ut hominem occidat nisi invenerit quod in homine perimat. cum eo solo conluctatur, † veluti praesentius invento.† sola haec pugna est, cum venenum in visceribus reperit, in homine conmoriuntur ut homo supersit. immo vero etiam ferarum remedia antiqui prodiderunt demonstrando quomodo venenata quoque ipsa sanarentur. torpescunt scorpiones aconiti tactu stupentque pallentes et vinci se confitentur. auxiliatur his helleborum album tactu resolvente, ceditque aconitum duobus malis, suo et omnium. quae si quis ulla forte ab homine excogitari potuisse credit, ingrate deorum munera intellegit. tangunt carnes aconito necantque gustatu earum pantheras, nisi hoc fieret, repleturas illos situs. ob id quidam pardalianches appellavere. at illas statim liberari morte excrementorum hominis gustu demonstratum. quod certe casu repertum quis dubitet et quotiens fiat etiam nunc ut novum nasci, quoniam feris ratio et usus inter se tradi non possit? hic ergo casus, hic est ille qui plurima in vita invenit deus, hoc habet nomen per quem intellegitur eadem et parens rerum omnium et magistra, utraque coniectura pari, sive ista cotidie feras invenire sive semper scire iudicemus. pudendumque rursus omnia animalia quae sint salutaria ipsis nosse praeter hominem. sed maiores oculorum quoque medicamentis aconitum misceri saluberrime promulgavere aperta professione malum quidem nullum esse sine aliquo bono. fas ergo nobis erit qui nulla diximus venena monstrare quale sit aconitum, vel deprehendendi gratia. folia habet cyclamini aut cucumeris non plura quattuor, ab radice, leniter hirsuta, radicem modicam cammaro similem marino, quare quidam cammaron appellavere, alii thelyphonon, ex qua diximus causa. cauda radicis incurvatur paulum scorpionum modo, quare et scorpion aliqui vocavere. nec defuere qui myoctonon appellare mallent, quoniam procul et e longinquo odore mures necat. nascitur in nudis cautibus quas aconas nominant, et ideo aconitum aliqui dixere, nullo iuxta ne pulvere quidem nutriente. hanc aliqui rationem nominis adtulere, alii, quoniam vis eadem esset in morte quae cotibus in ferri acie deterenda, statimque admota velocitas sentiretur.

But who could revere enough the diligent research of the ancients? It is established that of all poisons the quickest to act is aconite, and that death occurs on the same day if the genitals of a female creature are but touched by it. This was the poison that Marcus Caelius accused Calpurnius Bestia of using to kill his wives in their sleep. Hence the damning peroration of the prosecutor’s speech accusing the defendant’s finger. Fable has it that aconite sprang out of the foam of the dog Cerberus when Hercules dragged him from the underworld, and that this is why it grows around Heraclea in Pontus, where is pointed out the entrance to the underworld used by Hercules. Yet even aconite the ancients have turned to the benefit of human health, by finding out by experience that administered in warm wine it neutralizes the stings of scorpions. It is its nature to kill a human being unless in that being it finds something else to destroy. Against this alone it struggles, †regarding it as more pressing than the find.† [This is the only fight, when the aconite discovers a poison in the viscera.] What a marvel! Although by themselves both are deadly, yet the two poisons in a human being perish together so that the human survives. Moreover even remedies used by wild beasts have been handed down by the ancients, who have shown how venomous creatures also by themselves obtain healing. Scorpions, touched by aconite, become numbed, and are pale and stupefied, acknowledging their defeat. They find a help in white hellebore, its touch dispelling the torpor; the aconite yields to two evil foes, one peculiar to itself and one common to all creatures. If anyone believes that these discoveries could, by any chance, have been made by a man, he shows himself ungrateful for the gods’ gifts. They touch flesh with aconite, and kill panthers by a mere taste of it, otherwise panthers would overrun the regions where they are found. For this reason some have called aconite pardalianches, that is panther-strangler. But it has been proved that panthers are at once saved from this death by tasting human excrement; surely nobody doubts that this remedy has been found by Chance, and that on every occasion it is even today a new find, since wild animals have neither reason nor experience for results to be passed from one to another. This Chance therefore, this is that great deity who has made most of the discoveries that enrich our life, this is the name of him by whom is meant she who is at once the Mother and the Mistress of all creation. Either guess is equally likely, whether we judge that wild animals make these discoveries every day or that they possess a never-failing instinct. Again it is shameful that all animals except man know what is health-giving for themselves. Our ancestors however advertised the view that aconite is also a very health-giving ingredient of preparations for the eyes, openly declaring their belief that no evil at all is without some admixture of good. It will therefore be right for me, who have described no poisons, to point out the nature of aconite, if only for the purpose of detecting it. It has leaves like those of cyclamen or of cucumber, not more than four, rising from the root and slightly hairy, and a root of moderate size, like a crayfish (cammarus), whence some have called it cammaron, and others thelyphonon, for the reason I have given already. The end of the root curves up a little like a scorpion’s tail, whence some have called it also scorpion. There have been some who would prefer to call it myoctonos, [I.e. “mouse-killer”] since at a distance, even a long distance, its smell kills rats and mice. The plant grows on bare crags which are called aconae, and for that reason some have given it the name of aconite, there being nothing near, not even dust, to give it nourishment. This then is the reason for its name given by some; others have thought it was so named because it had the same power to cause rapid death as whetstones had to give an edge to an iron blade; no sooner was the stone applied than its rapid action was noticeable. [It is interesting to compare Pliny’s account of aconite with Dioscorides IV 76 (Wellmann). In the latter is given the effect of aconite on scorpions with its antidote in the touch of white hellebore. The preceding sentence is: ῥίζα ὁμοία σκορπίου οὐρᾷ, στίλβουσα ἀλαβαστροειδῶς. For this last Pliny has only: cauda radicis incurvatur paulum scorpionum modo. The phrase cauda radicis is peculiar, and suggests that Pliny had a Greek text before him in which ῥίζα and οὐρὰ (or some case of it) were side by side. There is nothing in Dioscorides corresponding to arida, which appears to have arisen from its partial likeness to cauda.]

Wolf’s-bane to Panthers and Wolves

Pliny viii. 27 § 41.

aconite

Aconitum (Jean Lemaire, Ill. des Gaules, I, 20): Aconite (d’Aubigné, IV, 74; Ronsard); Aconit (A. Paré). — Aconitum, genre de Renonculacées qui renferme divers principes toxiques, parmi lesquels des alcaloïdes, aconitine, napelline, etc. L’aconit à fleurs jaunes des Alpes, A. lycoctonum, L. (de λνχοζ, loup, χτείνω, je tue), ou tue-loup, contient un alcaloïde particulier que Goris distingue de l’aconitine sous le nom de lycoctonine. On le mêlait, haché, à une pâtée de viande pour empoisonner les loups et autres animaux maalfaisants: «Pantheras perfricatâ carne aconito, venenum id est, barbari venantur», dit Pline, VIII, 41, et XXVII, 2: «Tangunt carnes aconito, necantque gustatu earum pantheras». (Paul Delaunay)

pards

Léopard d’Afrique ou panthère (Felis pardus L.) pardalis d’Aristote, pardus de Lucain et de Pline, cf. H.N. VIII, 23: «Pardos, qui mares [pantheræ] sunt, appellant». (Paul Delaunay)

aconite

Plant vénéneuse utilisée dans des pâtées de viande pour tuer les nuisibles.

pard

pard. Also parde, perde. [adopted from Old French pard, part, parde, adaptation of Latin pardus panther, adopted from Greek pardoj, panther, leopard, or ounce, an Eastern word; compare Persian pars panther.]

A panther or leopard. (Now only an archaic or poetic name.)

A. 1300 Cursur Mundi (The Cursur of the World) 11629 Leon yode þam als Imid, And pardes als þe dragons did.

1382 John Wyclif Bible Jeremiah v. 6 A parde wakynge on the citees of hem.

1398 John de Trevisa Bartholomeus De proprietatibus rerus xviii. lxxxiii. (1495) 834 The perde varieth not fro the pantera, but the pantera hath moo white speckes.

1600 William Shakespeare As You Like It ii. vii. 150 Then, a Soldier, Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the Pard.

1657 W. Morice Coena quasi Koinhé Def. xxiv. 240 As mute..as a..Dogg bitten by a Pard.

1725 Alexander Pope, translator Odyssey iv. 616 Sudden, our band a spotted pard restrain.

1817 J. F. Pennie Royal Minstrel ii. 409 Has the fierce mountain pard assail’d the flock?

1820 John Keats Ode Nightingale iv, I will fly to thee, Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards.

aconite

aconite. [adopted from French aconit, adaptation of Latin aconit-um, adaptation of Greek a’ko´niton of uncertain etymology. The Latin form aconitum is also used unchanged.]

A genus of poisonous plants, belonging to the order Ranunculaceae. especially the common European species Aconitum Napellus, called also Monk’s-hood and Wolf’s-bane. Also applied loosely or erroneously to other poisonous plants

1578 Henry Lyte, translator Dodoens’ Niewe herball or historie of plantes 426 Aconit is of two sortes… the one is named Aconit that baneth, or killeth Panthers. The other… Aconit that killeth Woolfs.

1598 Sylvester Du Bartas i. iii. (1641) 27/1 Onely the touch of Choak-pard Aconite Bereaves the Scorpion both of sense and might.

1601 Philemon Holland, translator Pliny’s History of the world, commonly called the Natural historie II. 271 (1634) It groweth naturally vpon bare and naked rocks, which the Greeks cal Aconas: which is the reason (as some haue said) why it was named Aconitum.

1697 John Dryden, translator Virgil’s Georgicsii. 209 Nor pois’nous Aconite is here produc’d, Or grows unknown, or is, when known, refus’d.

An extract or preparation of this plant, used as a poison and in pharmacy. Poetic: Deadly poison.

1597 William Shakespeare 2 Henry IV, iv. iv. 48 Though it doe worke as strong As Aconitum, or rash Gun-powder.

1606 Thomas Dekker Newes from hell; brought by the diuells carrier (1842) 87 note, Ingenious, fluent, facetious T. Nash, from whose abundant pen hony flow’d to thy friends, and mortall aconite to thy enemies.

1656 Abraham Cowley Extracts from Anacreontiques i. (1669) 41 All the World’s Mortal to ‘em then, And Wine is Aconite to men.

aconite

In De Materia Medica (“The Materials of Medicine”), Dioscorides describes two different plants, the first Akoniton lycoctonum (IV.77), which was used as an anodyne (pain reliever) in eye medications, and to kill panthers, wolves, and other wild beasts. In the next chapter (IV.78), he describes “the other aconitum,” Aconitum napellus (monkshood), which also is poisonous and used to kill wolves. Aconitum napellus is so named, says Theophrastus (IX.16.4-5), because the tuberous root of the plant was thought to resemble a small turnip (napus) and “in this root resides its deadly property” (the alkaloid aconitine). He goes on to say that, depending upon how it is compounded, the effect of the poison can be immediate or fatal in several months or even a year or two—the longer the time, the more painful the death. In general, it was deadly to any four-footed animal and “kills them the same day if the root or leaf is put on the genitals” (IX.18.2).

pentaphyllon, which has five leaves

pentaphyllon, which has five leaves;

Original French: Pentaphyllon, qui ha cinq feueilles:

Modern French: Pentaphyllon, qui a cinq feueilles:

Among the plants named for their forms. The plants in this group also appear in Charles Estienne’s De Latinis et Graecis nominibus…[1], published in Paris in 1544, two years before the first edition of the Le Tiers Livre[2].

1. Estienne, Charles (1504–1564), De Latinis et Graecis nominibus arborum, fruticum, herbarum, piscium & avium liber : ex Aristotele, Theophrasto, Dioscoride, Galeno, Nicandro, Athenaeo, Oppiano, Aeliano, Plinio, Hermolao Barbaro, et Joanne Ruellio : cum Gallica eorum nominum appellatione. Paris: 1544. Bibliothèque nationale de France

2. Rabelais, François (1494?–1553), Le Tiers Livre des faictz et dictz Heroïques du noble Pantagruel: composez par M. François Rabelais docteur en Medicine, & Calloïer des Isles Hieres. L’auteur susdict supplie les Lecteurs benevoles, soy reserver a rire au soixante & dixhuytiesme livre. Paris: Chrestien Wechel, 1546. Gallica

Notes

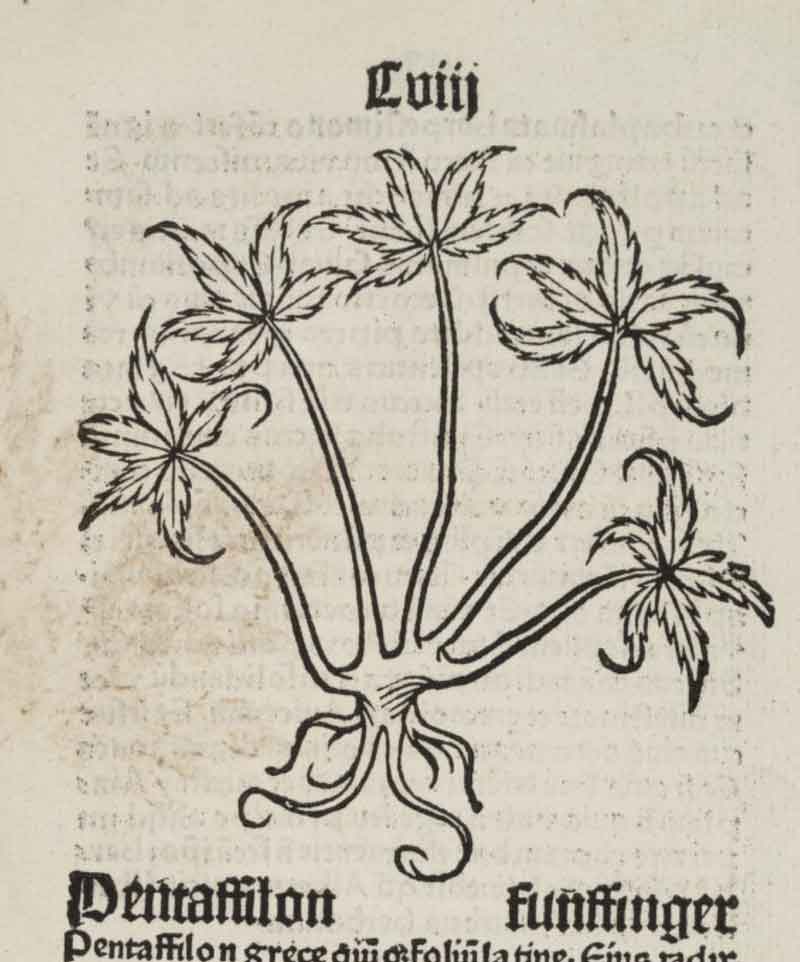

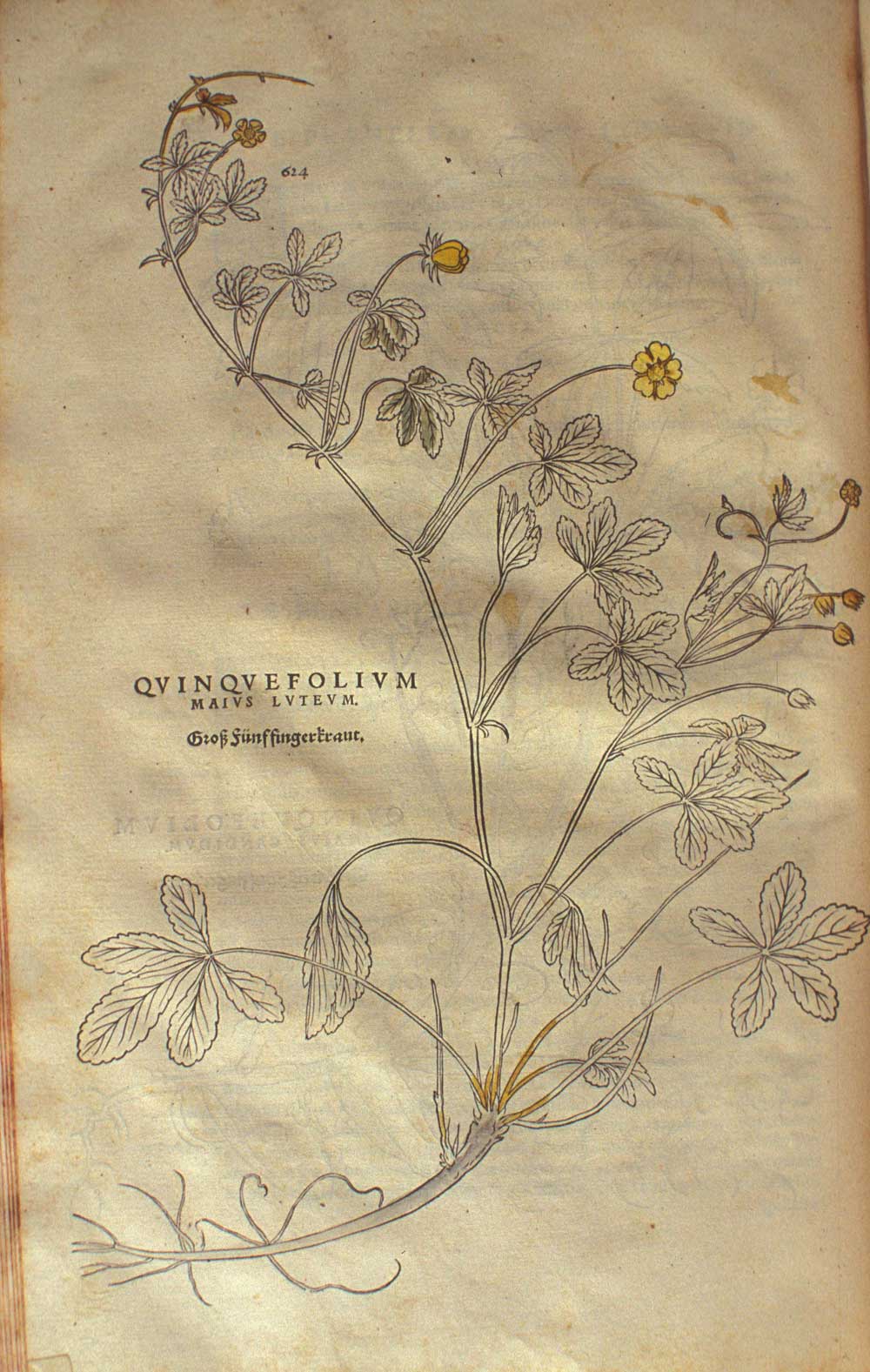

Pentassilon

Pentaphyllon

Quinquefolium

maius luteum

Gross funffingerkraut

Taxon: Potentilla reptans L.

Modern names:

English: creeping cinquefoil

French: quintefeuille

German: Fuenffingerkraut

pentaphyllon

Quinquefolium nulli ignotum est, cum etiam fraga gignendo commendetur, Graeci pentapetes aut pentaphyllon aut chamaezelon vocant. cum effoditur, rubram habet radicem. haec inarescens nigrescit et angulosa fit. nomen a numero foliorum. et ipsa herba incipit et desinit cum vite. adhibetur et purgandis domibus.

Cinquefoil is known to everyone, being popular for its actually producing strawberries. The Greeks call it pentapetes, pentaphyllon, or chamaezelon. When it is dug up it has a red root, which as it dries becomes black and angular. The name is derived from the number of the leaves. The plant itself buds and sheds its leaves with the vine. It is also used in purifying houses.

Pentaphyllon

Pliny xxv. 9, § 62.

Pentaphyllon

Pentaphyllon, quintefeuille, allusion aux feuilles digitées, à cinq foliole, del la plante. «Quinquefolium… Græci… pentaphyllon… vocant». (Pline, XXV, 62). C’est Potentilla reptans, L. (Rosacée.) (Paul Delaunay)

Les aultres de leurs formes

Encore une fois, tout cela se retrouve dans le petit livre de Charles Estienne, De latinis nominibus.

Pentaphyllon

Agrippa, De occulta philosophia, II, iii, précise que l’on voit dans les propriétes du pentaphyllon, appelé quintefeuille, les vertus du nombre quinaire.

cinquefoil

cinquefoil, cinqfoil. Forms: sinkfoil, (qwynfoile), synkfoil(e, cinkfoly, -ie, cinfoly, cinkfoile, (cinkefield), cinqfile, cinquefole, (cintfoyle), sinke-, synke-, sinckefoyle, cinke-, cinquefoile, -foyle, cinkfoil, sinkefoile, (sinkfield), cinqfoil, cinquefoil. [formed on Old French type *cinkfoil, modern French quintefeuille (quintefoil in Alphita, 15th c.), corresponding to Latin quinquefolium, formed on quinque five + folium leaf.]

The plant Potentilla reptans (N. O. Rosaceæ), with compound leaves each of five leaflets. Also used of other species with similar leaves, and as a book-name for the whole genus.

1545 Thomas Raynalde, The byrth of mankynde, otherwyse named the womans booke. 81 Take of cinkefoyle the leues and rotes.

1562 William Turner A new herball, the seconde parte (1568) ii. 110 b, Quinquefolium is named in English Cinkfoly, or fyvefyngred grasse, or herb fyvelefe.

1573 Thomas Tusser Fiue hundreth pointes of good husbandrie (1878) 97 Necessarie herbes to growe in the garden for Physick… Cinqfile.

1580 Hollyband Treas. French Tong., Quintefueille… an Hearbe called Cinkefield.

1589 Greene Menaphon (Arb.) 36 There growes the cintfoyle, and the hyacinth.

1676 Hobbes Iliad (1677) 33 Upon lote and cinquefoil feeding.

the long excuse of Penelope

and of the long excuse of Penelope towards her amorous suitors, during the absence of her husband Ulysses.

Original French: & de la longue excuſe de Penelope enuers ſes muguetz amoureux, pendant l’abſence de ſon mary Vlyxes.

Modern French: & de la longue excuse de Penelope envers ses muguetz amoureux, pendant l’absence de son mary Ulyxes.

Notes

Penelope weaving

The painting represents a scene from the Odyssey in an early Renaissance setting

Penelope

Therefore I pay no heed to strangers or to suppliants or at all to heralds, whose trade is a public one; instead, in longing for Odysseus I waste my heart away. So these men urge on my marriage, and I wind a skein of wiles. First some god breathed the thought in my heart to set up a great web in my halls and fall to weaving a robe—fine of thread was the web and very wide; and I at once spoke among them:

“‘Young men, my suitors, since noble Odysseus is dead, be patient, though eager for my marriage, until I finish this robe—I would not have my spinning come to nothing—a shroud for the hero Laertes against the time when the cruel fate of pitiless death shall strike him down; for fear anyone of the Achaean women in the land should cast blame upon me, if he were to lie without a shroud, who had won great possessions.’

“So I spoke, and their proud hearts consented. Then day by day I would weave at the great web, but by night would unravel it, when I had had torches placed beside me.

Pan

Now the Dionysus who was called the son of Semele, daughter of Cadmus, was about sixteen hundred years before my time, and Heracles son of Alcmene about nine hundred years; and Pan the son of Penelope (for according to the Greeks Penelope and Hermes were the parents of Pan) was about eight hundred years before me, and thus of a later date than the Trojan war.

146. With regard to these two, Pan and Dionysus, a man may follow whatsoever story he deems most credible; but I here declare my own opinion concerning them:—Had Dionysus son of Semele and Pan son of Penelope been made manifest in Hellas and lived there to old age, like Heracles the son of Amphitryon, it might have been said that they too (like Heracles) were but men, named after the older Pan and Dionysus, the gods of antiquity; but as it is, the Greek story has it that no sooner was Dionysus born than Zeus sewed him up in his thigh and carried him away to Nysa in Ethiopia beyond Egypt; and as for Pan, the Greeks know not what became of him after his birth. It is therefore plain to me that the Greeks learnt the names of these two gods later than the names of all the others, and trace the birth of both to the time when they gained the knowledge.

Pan

As for death among such beings [gods and demigods], I have heard the words of a man who was not a fool nor an impostor. The father of Aemilianus the orator, to whom some of you have listened, was Epitherses, who lived in our town and was my teacher in grammar. He said that once upon a time in making a voyage to Italy he embarked on a ship carrying freight and many passengers. It was already evening when, near the Echinades Islands, the wind dropped, and the ship drifted near Paxi. Almost everybody was awake, and a good many had not finished their after-dinner wine. Suddenly from the island of Paxi was heard the voice of someone loudly calling Thamus, so that all were amazed. Thamus was an Egyptian pilot, not known by name even to many on board. Twice he was called and made no reply, but the third time he answered; and the caller, raising his voice, said, ‘When you come opposite to Palodes,a announce that Great Pan is dead.’ On hearing this, all, said Epitherses, were astounded and reasoned among themselves whether it were better to carry out the order or to refuse to meddle and let the matter go. Under the circumstances Thamus made up his mind that if there should be a breeze, he would sail past and keep quiet, but with no wind and a smooth sea about the place he would announce what he had heard. So, when he came opposite Palodes, and there was neither wind nor wave, Thamus from the stern, looking toward the land, said the words as he had heard them: ‘Great Pan is dead.’ Even before he had finished there was a great cry of lamentation, not of one person, but of many, mingled with exclamations of amazement. As many persons were on the vessel, the story was soon spread abroad in Rome, and Thamus was sent for by Tiberius Caesar. Tiberius became so convinced of the truth of the story that he caused an inquiry and investigation to be made about Pan; and the scholars, who were numerous at his court, conjectured that he was the son born of Hermes and Penelopê.

muguet

A fond woer, or courter of wenches; an effiminate youngster, a spruce Carpet-knight; also, a curiously-dressed babie of clowts.

Muguets amoureux

Muguets amoureux] Plus bas encore, l. 4 chap 43., le vent de la chemise pour les muguets & amoureux. Muguet, amoureux qui se parfume de musc.

Muguets amoureux

Plus bas encore, livre IV, chapitre xliii, le vent de la chemise pour les muguets et amoureux. Un muguet ici n’est pas tant un amoureux qui sent le musc, qu’un amant qui juge de sa maîtresse, comme si le musc et l’ambre lui sortoient de par-tout. (L.)

Penelope

Homer Od. xix. 138-150.

Penelope

Cf. Homère, Odyssée, XIX, v. 138-150

Penelope’s excuse

In other words, they prefer to spin or weave.

Penelope

Pénélope, symbole de la fidélité conjugale, tissait une tapisserie pendant le jour et la défaisait la nuit pour lasser les prétendants à qui elle avait promis de choisir un mari quand la tapisserie serait terminée (Odyssée, xix).

la longue excuse de Penelope

Homère, Odyssée, XIX,v. 138; toutes ces figures féminines ont un rapport avec le fil : les Parques filaient la vie des hommes; Virgile nous montre Circé occupée à tisser pendant la nuit; Pénélope tissait en attendant le retour d’Ulysse.

Fragment 510885

Wouldn’t perish the toll-rates and rent-rolls?

Original French: Ne periroient les Pantarques & papiers rantiers?

Modern French: Ne periroient les Pantarques & papiers rantiers?

pancarte

A paper containing the particular rates of Tolls, or Customes due unto the King, &c; thus tearmed, because, commonly, hung up in some publicke plase either single, or within a frame.

pantarques

Les pancartes, dont pantarques est une métathèse.

Œuvres de Rabelais (Edition Variorum)

p. 280

Charles Esmangart [1736-1793], editor

Paris: Chez Dalibon, 1823

Google Books

pantarche

(Glossary) pantarque, pancarte, paperasses.

Œuvres

L. Jacob (pseud. of Paul Lacroix) [1806–1884], editor

Paris: Charpentier, 1857

Google Books

pantarques

Pancartes. Cf. l. I, ch VIII, n. 3.

Oeuvres. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre

p. 366

Abel Lefranc [1863-1952], editor

Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931

Archive.org

pantarques

Les titres de rent.

Le Tiers Livre

P. 464

Jean Céard, editor

Librarie Général Français, 1995

pantarch

pantarch. Obsolete rare. [adopted from French pantarche, -arque (Rabelais), erron. form of pancarte pancart.]

A paper; a general chart.

1694 Motteux Rabelais, Pantagueline Prognostications To Rdr., I have tumbled over and over all the Pantarchs of the Heavens, calculated the Quadrates of the Moon.

panchart

panchart. Obsolete [adaptation of medieval Latin pancharta (-carta), formed on Greek pan- all + Latin charta leaf, paper, in medieval Latin `charter’.]

A charter, originally apparently one of a general character, or that confirmed all special grants, but in later use applied to almost any written record.

1621 John Molle, translator Camerarius’ Living Library v. xi. 361 The Constitutions of the Emperor Charles the fourth, gathered together in the Panchart, commonly called the Golden Bull.