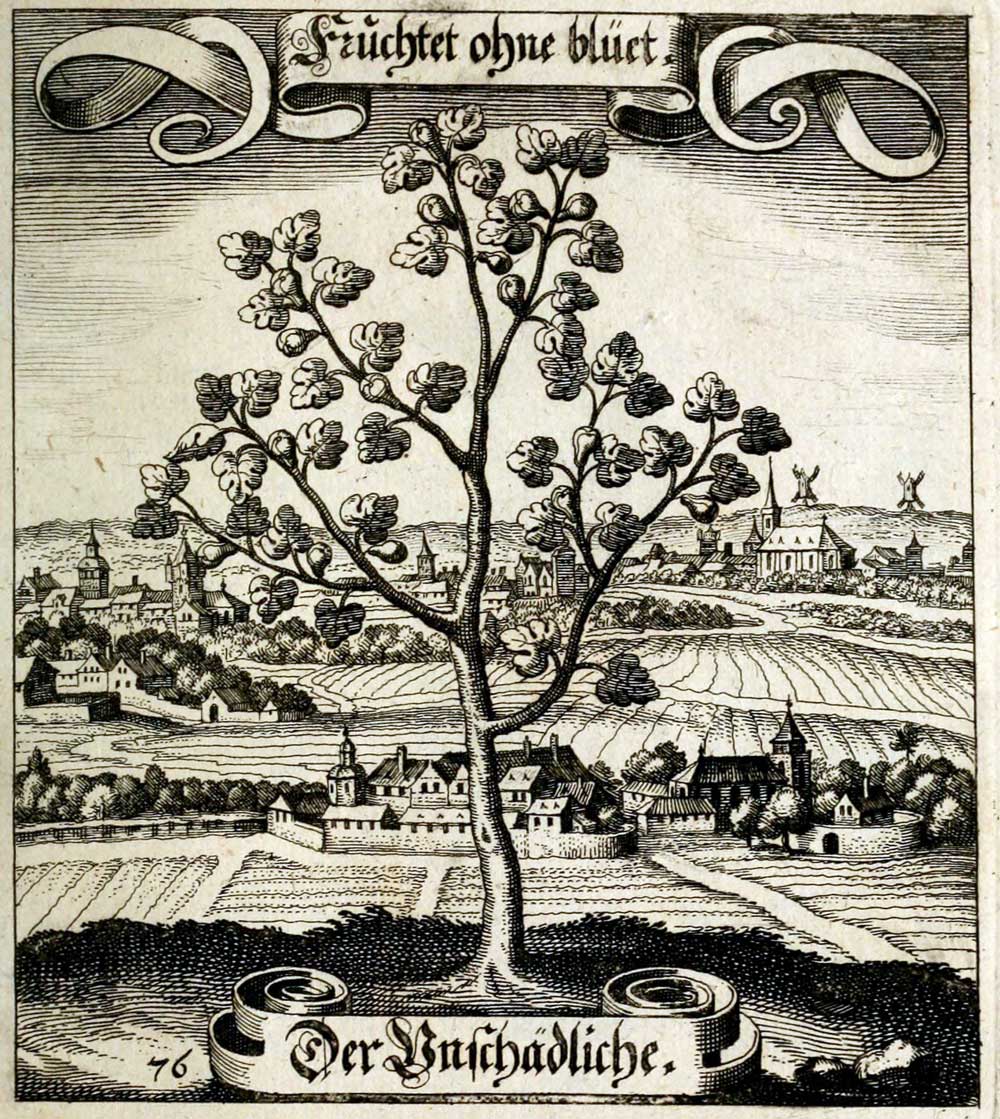

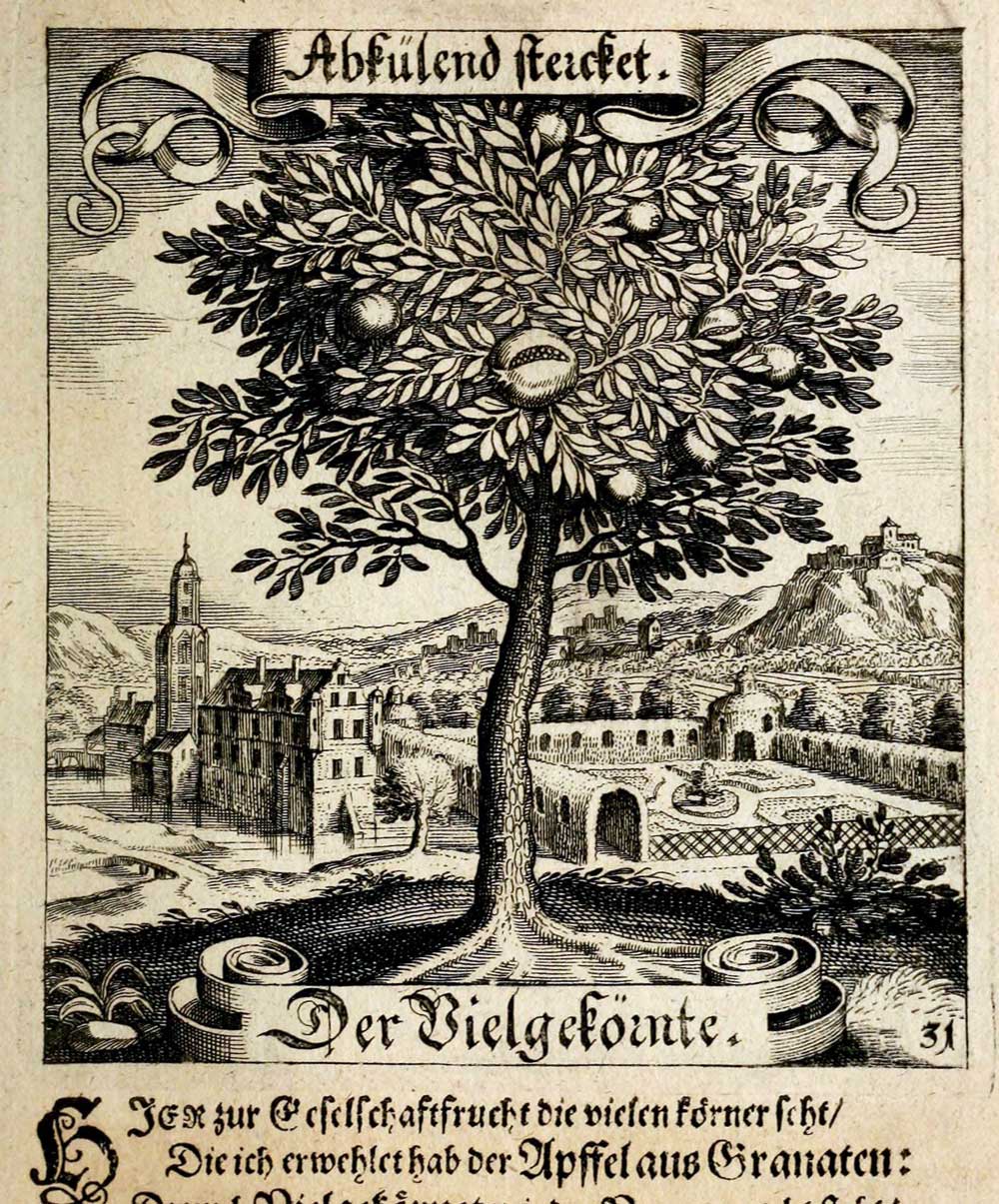

Original French: Heliotrope, c’eſt Soulcil, qui ſuyt le Soleil. Car le Soleil leuant, il s’eſpanouiſt: montant, il monte: declinant, il decline: ſoy cachant, il ſe clouſt.

Modern French: Heliotrope, c’est Soulcil, qui suyt le Soleil. Car le Soleil levant, il s’espanouist: montant, il monte: declinant, il decline: soy cachant, il se cloust.

Notes

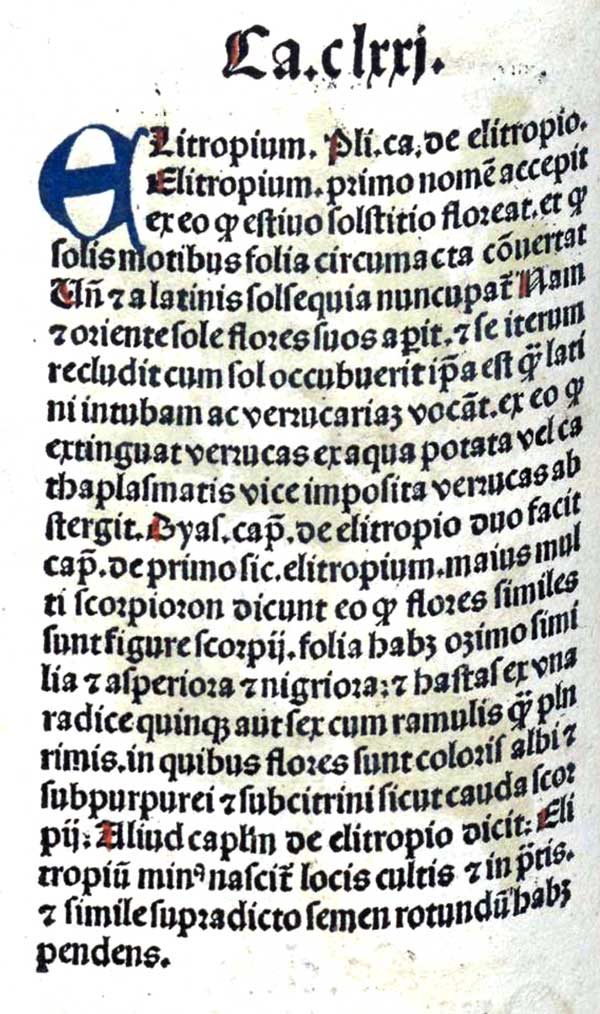

Elitropium

Elitropium (text)

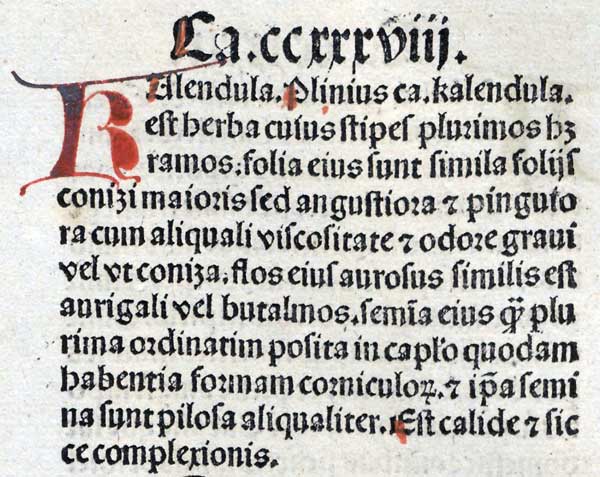

Kalendula

Kalendula (text)

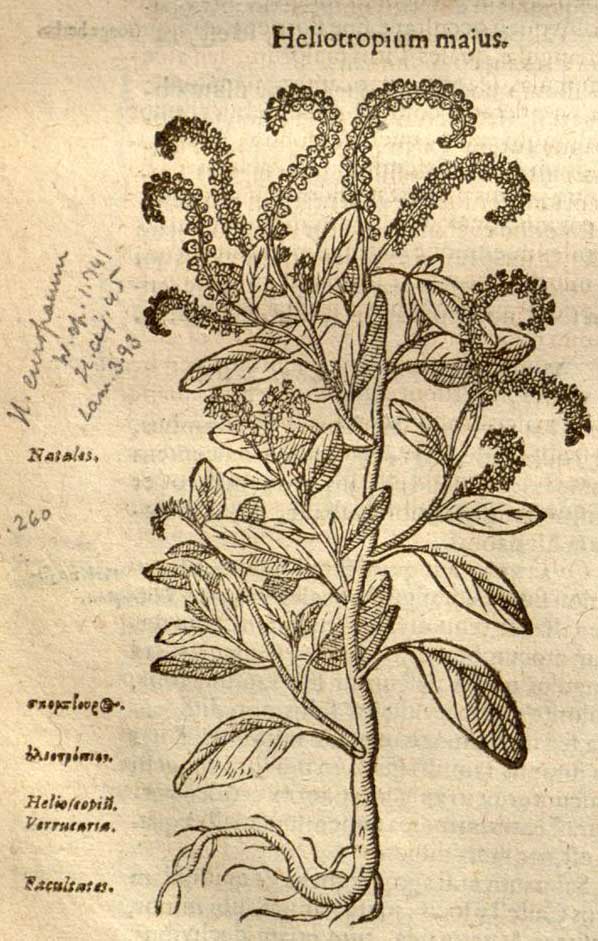

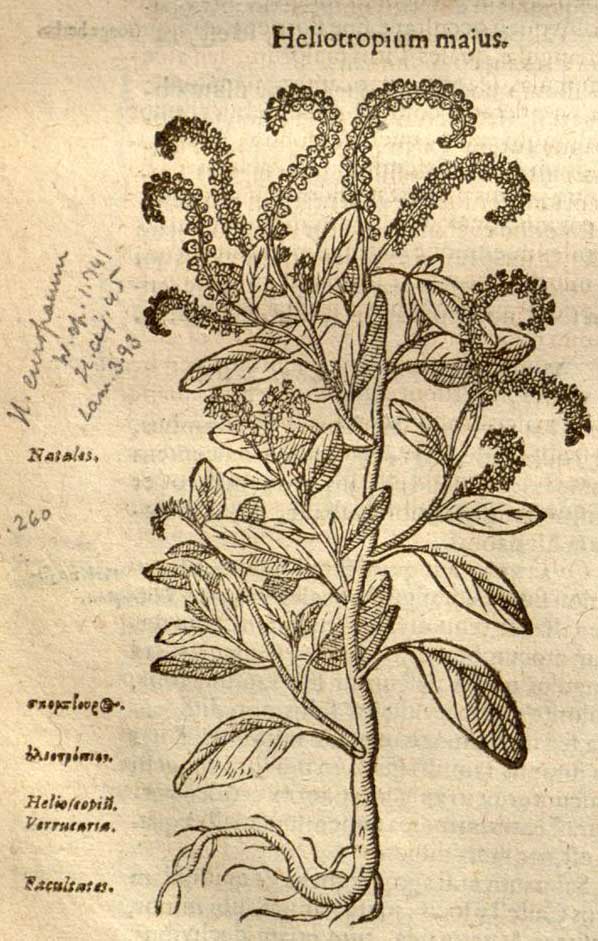

Heliotropium

Heliotropium europaeum L. [as Heliotropium majus]

Clusius, Carolus (1526-1609),

Rariorum plantarum historia vol. 1. Antverpiae: Joannem Moretum, 1601.

Plantillustrations.org

heliotrope

miretur hoc qui non observet cotidiano experimento herbam unam, quae vocatur heliotropium, abeuntem solem intueri semper omnibusque horis cum eo verti vel nubilo obumbrante.

This may surprise one who does not notice in daily experience that one plant, called heliotrope, always looks towards the sun as it passes and at every hour of the day turns with it, even when it is obscured by a cloud

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 1: Books 1 – 2. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1938. 02.41.

Loeb Classical Library

heliotrope

Iam vergilias in caelo notabiles caterva fecerat; non tamen his contenta terrestres fecit alias, veluti vociferans: ‘Cur caelum intuearis, agricola? cur sidera quaeras, rustice? iam te breviore somno fessum premunt noctes. ecce tibi inter herbas tuas spargo peculiares stellas easque vespera et ab opere disiungenti ostendo ac ne possis praeterire miraculo sollicito: videsne ut fulgor igni similis alarum conpressu obtegatur secumque lucem habeant et nocte dedi tibi herbas horarum indices et, ut ne sole quidem oculos tuos terra avoces, heliotropium ac lupinum circumaguntur cum illo. cur etiamnum altius spectes ipsumque caelum scrutere? habes ante pedes tuos ecce vergilias.’ incertis hae diebus proveniunt durantque, sed esse sideris huiusce partum eas certum est. proinde quisquis aestivos fructus ante illas severit ‘ipse frustrabitur sese.’ hoc intervallo et apicula procedens fabam florere indicat, fabaque florescens eam evocat. dabitur et aliud finiti frigoris indicium: cum germinare videris morum, iniuriam postea frigoris timere nolito.

She [Nature] had already formed the remarkable group of the Pleiads in the sky; yet not content with these she has made other stars on the earth, as though crying aloud: ‘Why gaze at the heavens, husbandman? Why, rustic, search for the stars? Already the slumber laid on you by the nights in your fatigue is shorter. Lo and behold, I scatter special stars for you among your plants, and I display them to you in the evening and as you unyoke to leave off work, and I stimulate your attention by a marvel so that you may not be able to pass them by: do you see how their fire-like brilliance is screened by their folded wings, and how they carry daylight with them even in the night? I have given you plants that mark the hours, and in order that you may not even have to avert your eyes from the earth to look at the sun, the heliotrope and the lupine revolve keeping time with him. Why then do you still look higher and scan the heavens themselves? Lo! you have Pleiads at your very feet.’ Glow-worms do not make their appearance on fixed days or last a definite period, but certain it is that they are the offspring of this particular constellation. Consequently anybody who does his summer sowing before they appear ‘will have himself to thank for labour wasted’. In this interval also the little bee comes forth and announces that the bean is flowering, and the bean begins to flower to tempt her out. We will also give another sign of cold weather being ended: when you see the mulberry budding, after that you need not fear damage from cold.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 18.252.

Loeb Classical Library

heliotrope

Heliotropi miraculum saepius diximus cum sole se circumagentis etiam nubilo die, tantus sideris amor est. noctu velut desiderio contrahit caeruleum florem.

I have spoken more than once [See II. § 109, XVIII. § 252] of the marvel of heliotropium, which turns round with the sun even on a cloudy day, so great a love it has for that luminary. At night it closes its blue flower as though it mourned [Or, “were afflicted with longing”].

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 6: Books 20–23. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1951. 22.29.

Loeb Classical Library

Espanir

To blow, or spread, as a blooming Rose, or any other flower, in the height of it flourishing; also, to display, stretch, or spread out.

Cotgrave, Randle (–1634?),

A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongue. London: Adam Islip, 1611.

PBM

Solsy

Soulcy ou souci: du latin solsequium, mot composé de sol et sequi, qui suit le soleil; comme heliotrope vient du grec λιοζ[?], sol, et τρίπσ[?], verto, flos ad solem se convertens.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Œuvres de Rabelais (Edition Variorum). Tome Cinquième. Charles Esmangart (1736–1793), editor. Paris: Chez Dalibon, 1823. p. 269.

Google Books

Espanir

Espanir, espennir, verbe. Refl., s’ouvrir, s’épanouir, se dilater, eclater:

Ce fu en jung, par un lundi

Qi le solaus clers s’espani.

— Parton., 2361, Crapelet

La rose espanissoit chacun jor devant sa fenestre. (Lancelot, ms Fribourg, fo. 59)

Godefroy, Frédéric (1826–97),

Dictionaire de l’ancienne langue Française. Et du tous ses dialectes du IXe au XVe Siècle. Paris: Vieweg, Libraire-Éditeur, 1881-1902.

Lexilogos – Dictionnaire ancien français

Heliotrope

Pliny ii. 41, § 41; Ov. Met. iv. 256-270.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

heliotrope

“But Clytie, though love could excuse her grief, and grief her tattling, was sought no more by the great light-giver, nor did he find aught to love in her. Thereafter she pined away, her love turned to madness. Unable to endure her sister nymphs, beneath the open sky, by night and day, she sat upon the bare ground, naked, bareheaded, unkempt. For nine whole days she sat, tasting neither drink nor food, her hunger fed by naught save pure dew and tears, and moved not from the ground. Only she gazed on the face of her god as he went his way, and turned her face towards him. They say that her limbs grew fast to the soil and her deathly pallor changed in part to a bloodless plant; but in part ’twas red, and a flower, much like a violet, came where her face had been. Still, though roots hold her fast, she turns ever towards the sun and, though changed herself, preserves her love unchanged.” The story-teller ceased; the wonderful tale had held their ears. Some of the sisters say that such things could not happen; others declare that true gods can do anything. But Bacchus is not one of these.

Alcithoë is next called for when the sisters have become silent again. Running her shuttle swiftly through the threads of her loom, she said: “I will pass by the well-known love of Daphnis, the shepherd-boy of Ida, whom a nymph, in anger at her rival, changed to stone: so great is the burning smart which jealous lovers feel. Nor will I tell how once Sithon, the natural laws reversed, lived of changing sex, now woman and now man. How you also, Celmis, now adamant, were once most faithful friend of little Jove; how the Curetes sprang from copious showers; how Crocus and his beloved Smilax were changed into tiny flowers. All these stories I will pass by and will charm your minds with a tale that is pleasing because new.

“How the fountain of Salmacis is of ill-repute, how it enervates with its enfeebling waters and renders soft and weak all men who bathe therein, you shall now hear. The cause is hidden; but the enfeebling power of the fountain is well known. A little son of Hermes and of the goddess of Cythera the naiads nursed within Ida’s caves. In his fair face mother and father could be clearly seen; his name also he took from them. When fifteen years had passed, he left his native mountains and abandoned his foster-mother, Ida, delighting to wander in unknown lands and to see strange rivers, his eagerness making light of toil. He came even to the Lycian cities and to the Carians, who dwell hard by the land of Lycia. Here he saw a pool of water crystal clear to the very bottom. No marshy reeds grew there, no unfruitful swamp-grass, nor spiky rushes; it is clear water. But the edges of the pool are bordered with fresh grass, and herbage ever green. A nymph dwells in the pool, one that loves not hunting, nor is wont to bend the bow or strive with speed of foot. She only of the naiads follows not in swift Diana’s train. Often, ’tis said, her sisters would chide her: ‘Salmacis, take now either hunting-spear or painted quiver, and vary your ease with the hardships of the hunt.’ But she takes no hunting-spear, no painted quiver, nor does she vary her ease with the hardships of the hunt; but at times she bathes her shapely limbs in her own pool; often combs her hair with a boxwood comb, often looks in the mirror-like waters to see what best becomes her. Now, wrapped in a transparent robe, she lies down to rest on the soft grass or the soft herbage. Often she gathers flowers; and on this occasion, too, she chanced to be gathering flowers when she saw the boy and longed to possess what she saw.

Ovid (43 BC-AD 17/18),

Metamorphoses. Volume I: Books 1–8. Frank Justus Miller (1858–1938), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1916. 4.256 f.

Loeb Classical Library

heliotrope

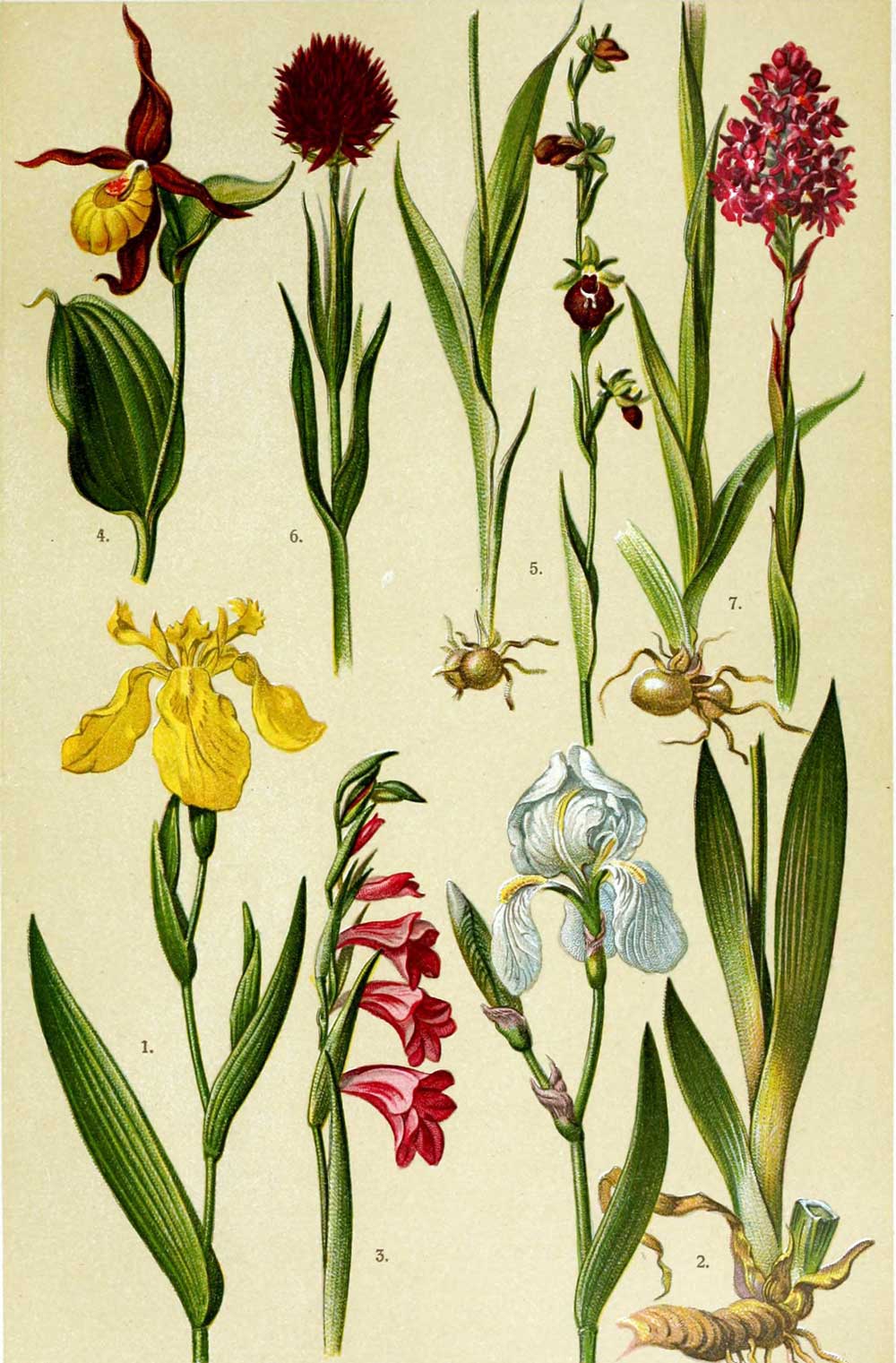

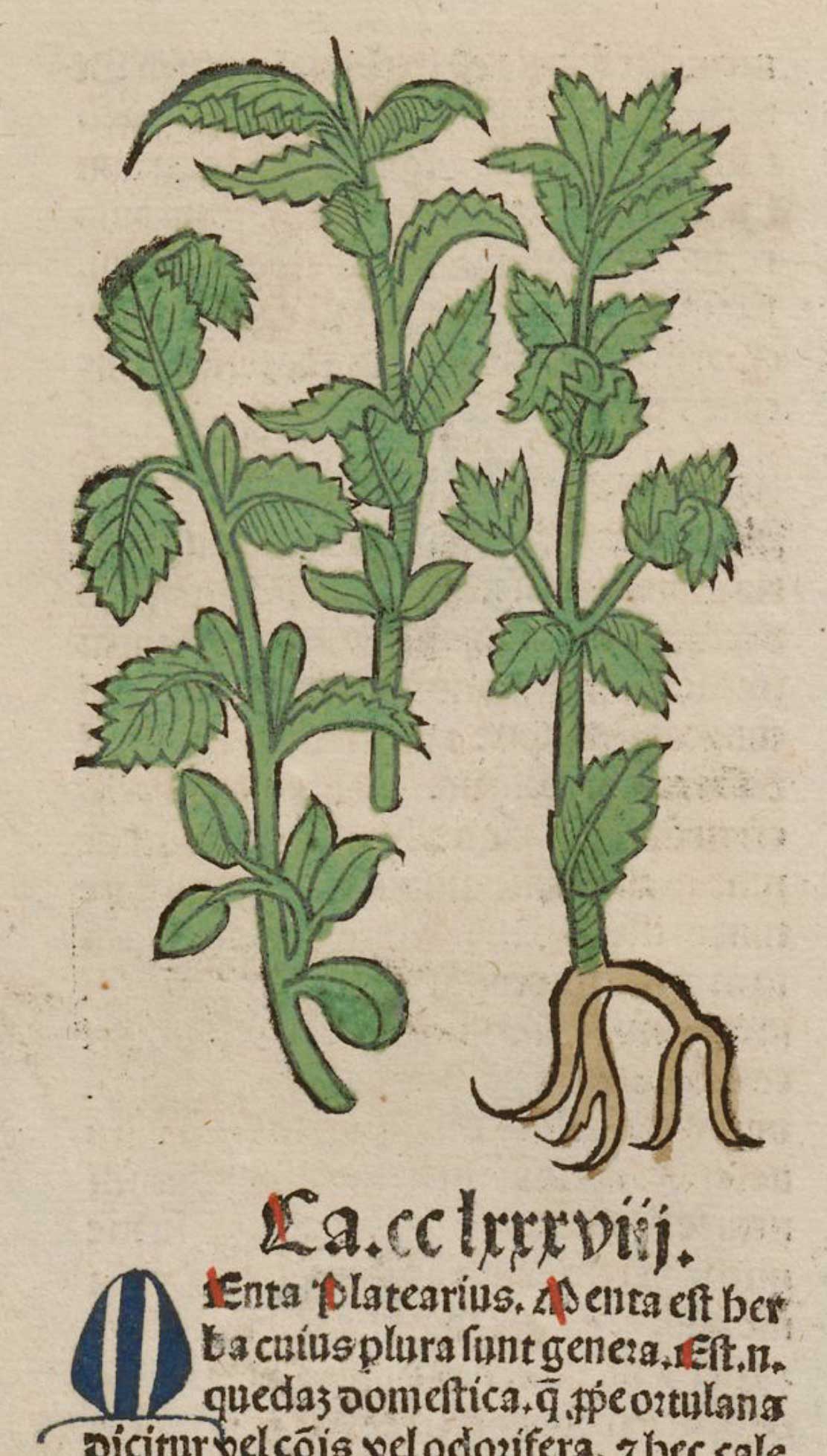

«Heliotropii miraculum sæpius diximus, cum sole se circumagentis, etiam nubilo die». Pline, XXII, 29. Pline en distingue deux espèces: l’helioscopium ou verrucaria qui est, pour Fée, notre herbe aux verrues, Heliotropium europæum, L.; et le tricoccum qui est, pour Fée. le tournesol, Croton tinctorium, L. Crozophora tinctoria Neck. L’héliotrope est trop diversement décrit par les anciens pour que ces identifications soient certaines: Hœfer veut voir dans le Soleil (Helianthus annuus, L.) l’heliotropium de Dioscorde et Pline, oubliant que c’est une plante du Pérou. Reutter dit que l’Heliotropium des contemporains de Théophraste et d’Horace est la plante dite Sponsa solis, solsequium, notre chicorée sauvage, Cichorium intybus, L. Quant à Rabelais, il se soucie assez peu de préciser des plantes qu’il ne cite que par parade d’érudition: H. Sainéan (H. N. R., p. 120) pense que son Héliotrope est H. europæum; mais je ne sache pas que celui-ci ait jamais porté le nom de Souci. On lit dans Matthiole que le nom d’heliotropium fut parfois appliqué a un Catha: or, le Catha poetarum de Pene et Lobel est bien notre Calendula arvensis, L., ou souci. (Paul Delaunay).

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 352.

Internet Archive

par les admirables qualitez

Cf. encore, De latinis nominibus pour tous ces détails. Le seule exemple qui ne s’explique pas de soi-même est hieracia; «Hieracum nomen ex eo venit quod [l’epevier] succo hujus herbae oculorum obscuritatem discutiant». Eryngion (« barbe à bouc ») serait un contrepoison. Que-fait-il dans cette liste?

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Le Tiers Livre. Edition critique. Michael A. Screech (b. 1926), editor. Paris-Genève: Librarie Droz, 1964.

Heliotrope

Pline, XXII, xxix.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Œuvres complètes. Mireille Huchon, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1994. p. 504, n. 18.

heliotrope

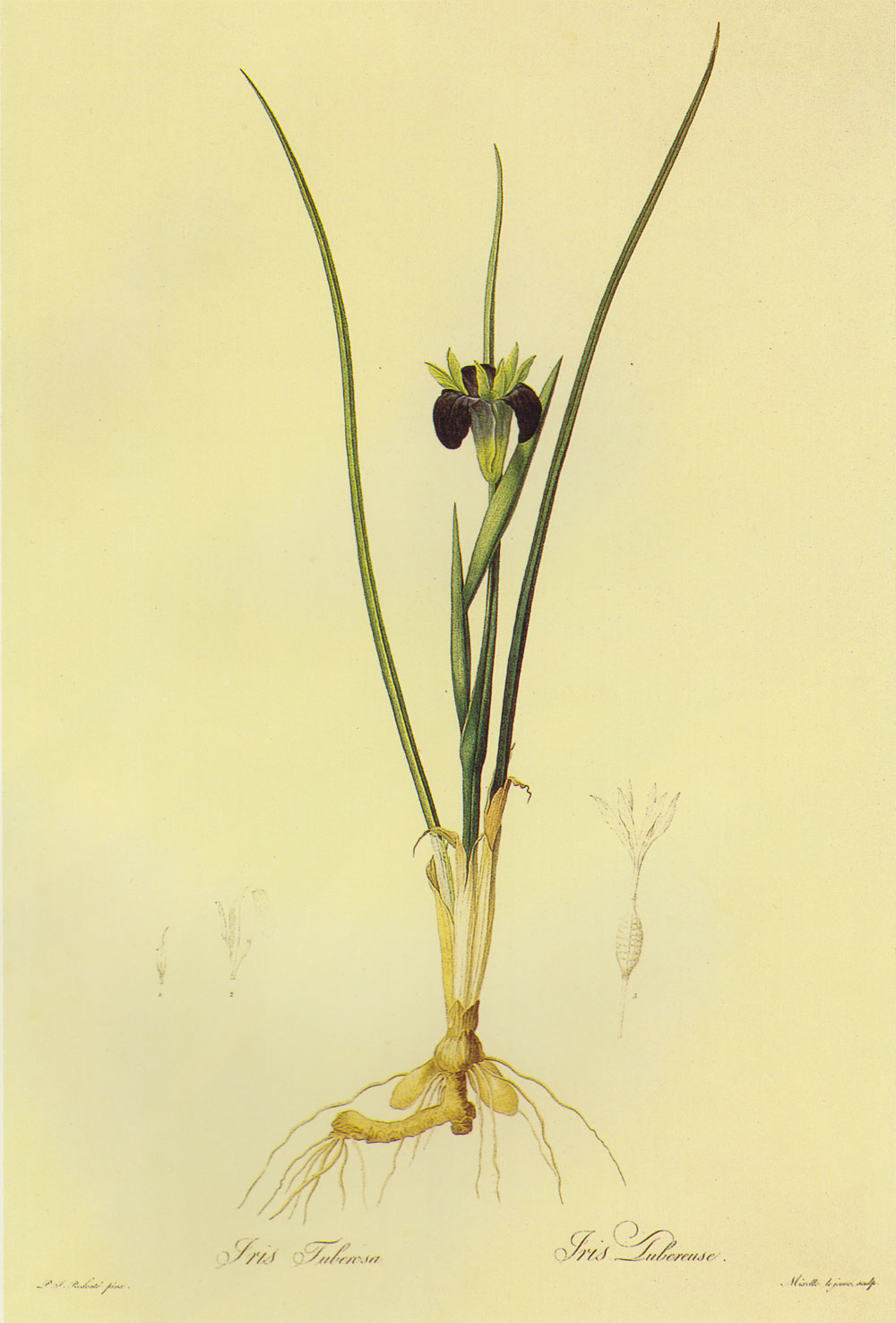

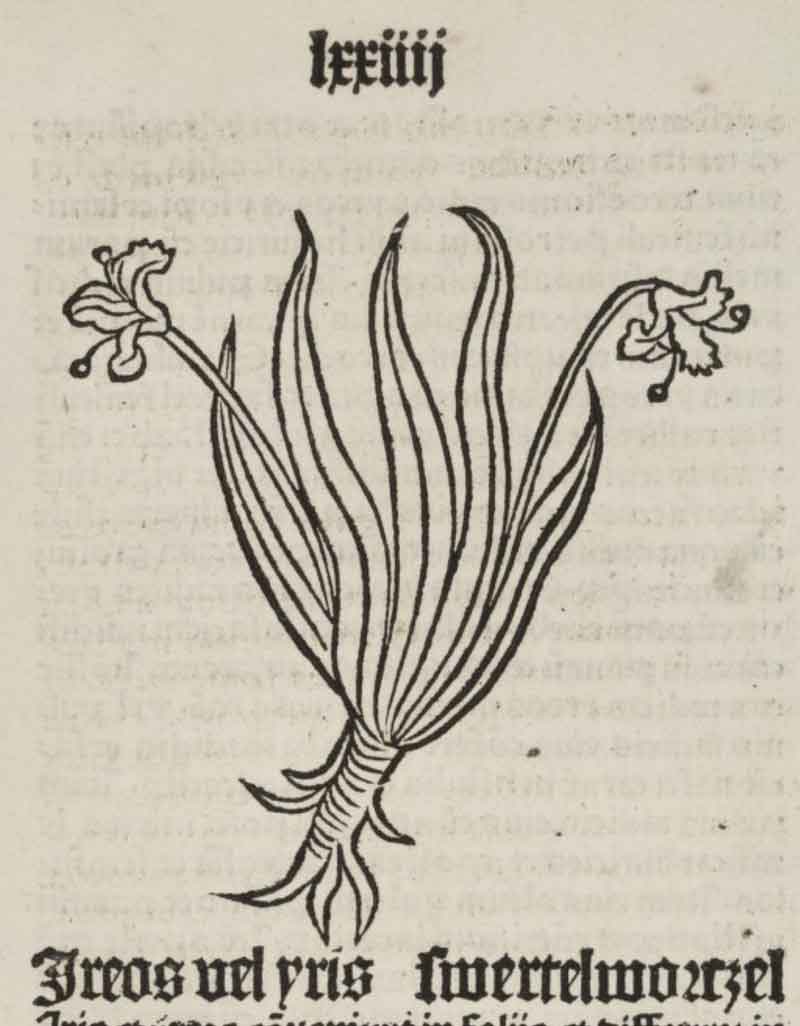

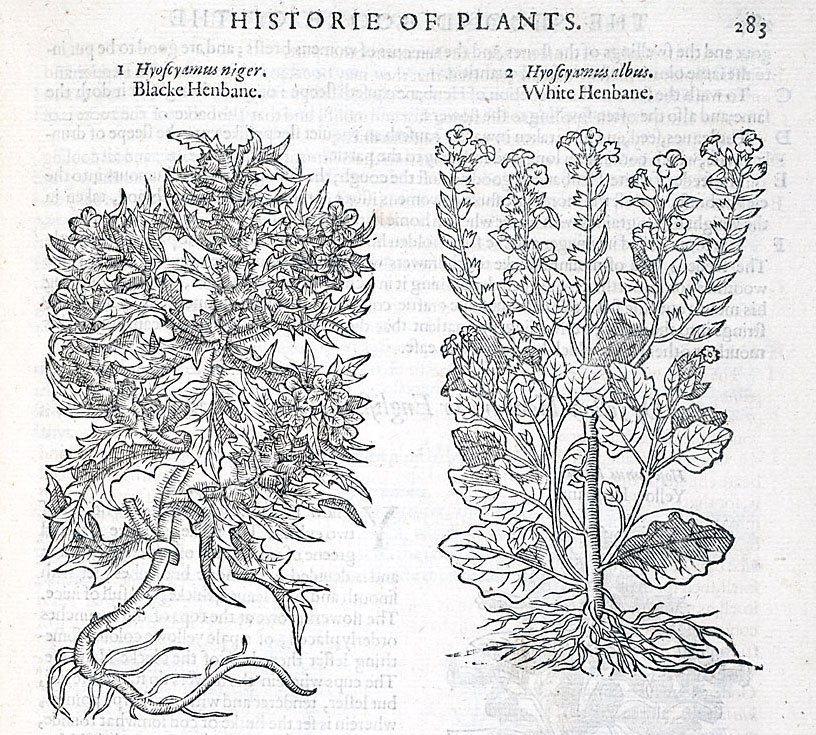

heliotrope. Forms: eliotropus, elitropium, -ius, eliotropia, helytropium, heliotropion. [Formerly in Lat. form heliotropium, etc., adopted from Greek heliotropion, a plant which turns its flowers and leaves to the sun, heliotrope; also a green stone streaked with red, bloodstone, and a kind of sundial; formed on helioj sun + –tropoj turning, trepein to turn. In current form, adopted from French héliotrope (16th century in Hatzfeld and Darmesteter, Dictionnaire général de la langue française).]

A name given to plants of which the flowers turn so as to follow the sun; in early times applied to the sunflower, marigold, etc.; now, a plant of the genus Heliotropium (N.O. Ehretiaceæ or Boraginaceæ), comprising herbs or shrubs with small clustered purple flowers.

AC. 1000 Saxon Leechdoms, Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England I. 254 Ðeos wyrt þe man eliotropus and oðrum naman si&asg.ilhweorfa nemneð.

1398 John de Trevisa Bartholomeus De proprietatibus rerus xvii. liv. (1495) 635 Elitropium is a drye herbe and… it beeryth and tornyth the leyf abowte wyth the meuynge of the sonne.

1549 Complaynt of Scotlande vi. 57 Siklyik, ther is ane eirb callit helytropium, the quhilk the vulgaris callis soucye; it hes the leyuis appin as lang as the soune is in our hemispere, and it closis the leyuis, quhen the soune passis vndir our orizon.

C. 1590 Robert Greene French Bacon xvi. 58 Apollo’s heliotropion then shall stoop And Venus hyacinth shall vail her top.

1603 Ben Jonson King’s Coronation Entertain. Wks. (Rtldg.) 528/2 Her chaplet [was] of Heliotropium, or turnsole.

1664 John Evelyn Kalendarium hortense (1729) 215 Star-wort, Heliotrop, French Marigold.

1676 Marvell Mr. Smirke I bis, As the Heliotrope Flower that keeps its ground, but wrests its Neck in turning after the warm Sun.

Mineralogy. A green variety of quartz, with spots or veins of red jasper; also called bloodstone; anciently credited with various `virtues’, as that of stanching blood, rendering the wearer invisible, etc. (As to the origin of the name see quot. 1601.)

A1390 John Gower Confessio amantis III. 112 There sitten five stones mo… Jaspis and elitropius.

1398 John de Trevisa Bartholomeus De proprietatibus rerus xvi. xl. (1495) 566 Eliotropia is a precyous stone and is grene and spronge wyth red dropes and veynes of colour of blood.

1601 Philemon Holland, translator Pliny’s History of the world, commonly called the Natural historie II. 627 The pretious stone Heliotropium… is a deepe green in maner of a leeke… garnished with veins of bloud: the reason of the name Heliotropium is this, For that if it be throwne into a pale of water, it changeth the raies of the Sun by way of reuerberation into a bloudie colour… Magitians… say, that if a man carrie it about him… he shall goe inuisible.

1587 Golding translator Solinus’ Polyhistor (1590) S ij b (Stanf.), The precious stone called Heliotrope.

1814 Cary Dante’s Inferno xxiv. 91 Nor hope had they of crevice where to hide, Or heliotrope to charm them out of view.

![Hermodattulus. Peter Schöffer, <em>[R]ogatu plurimo[rum]</em>, 1484 Hermodattulus](/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/schoffer-hermodattulus.jpg)