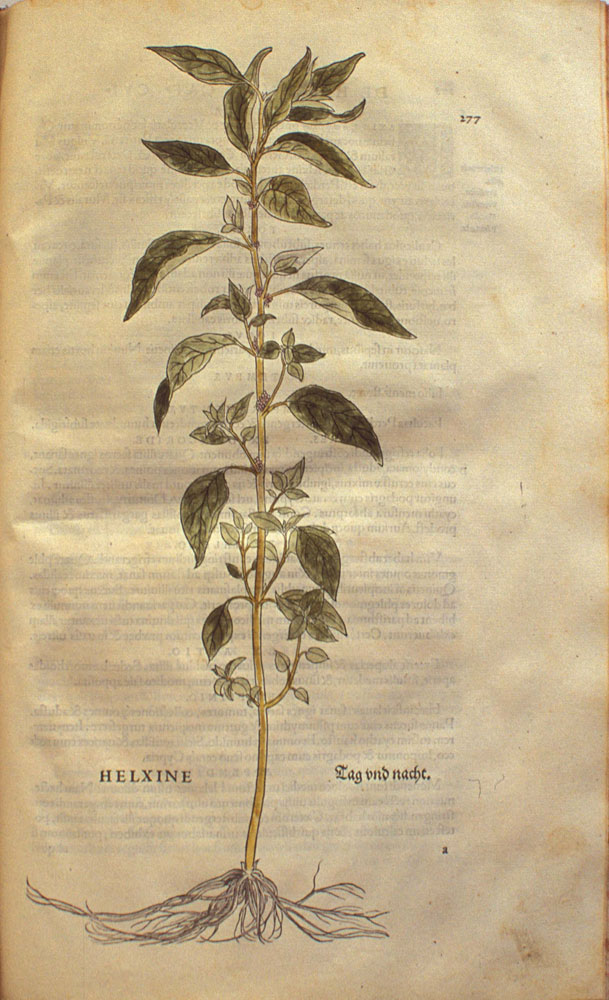

Notes

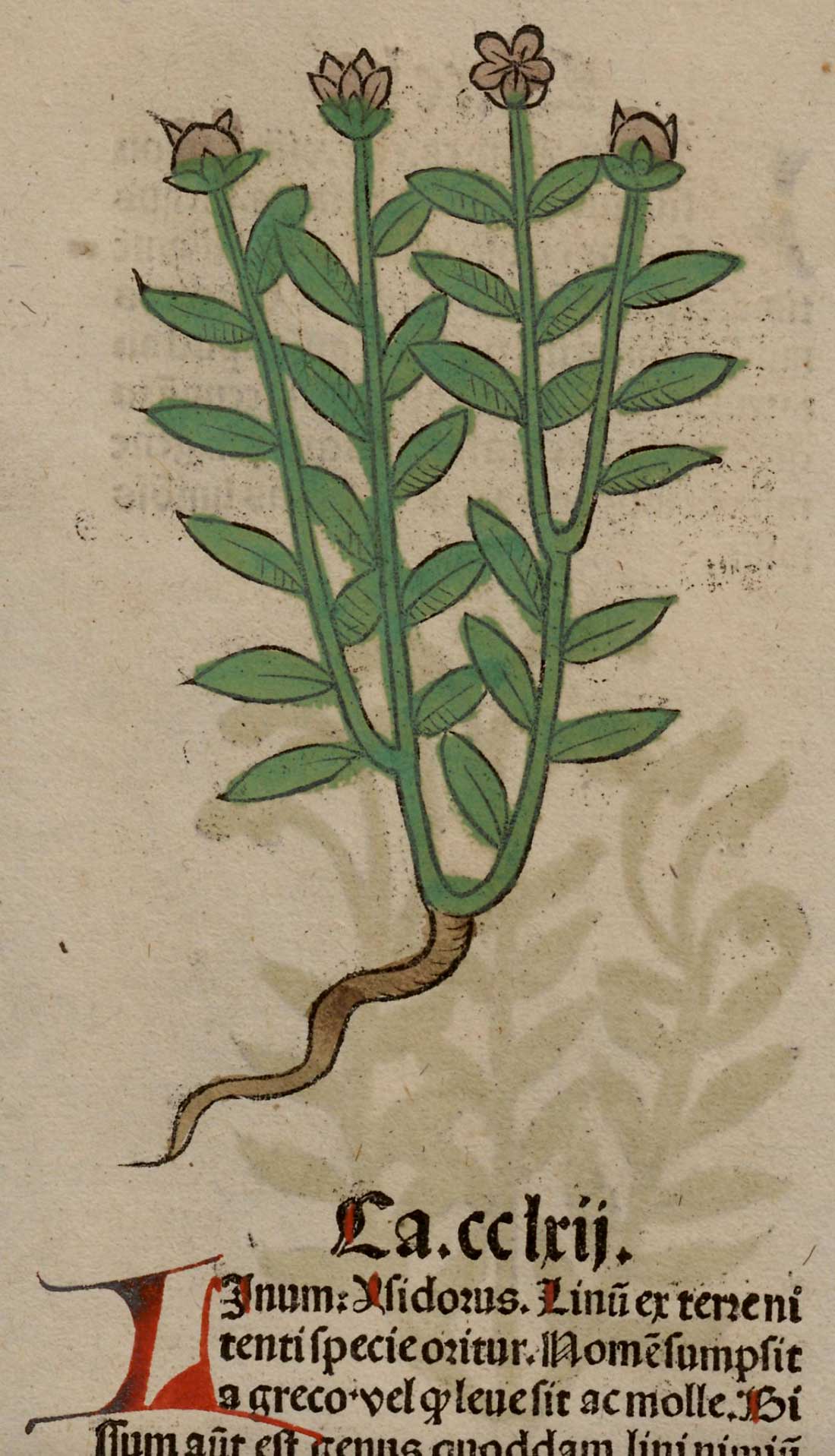

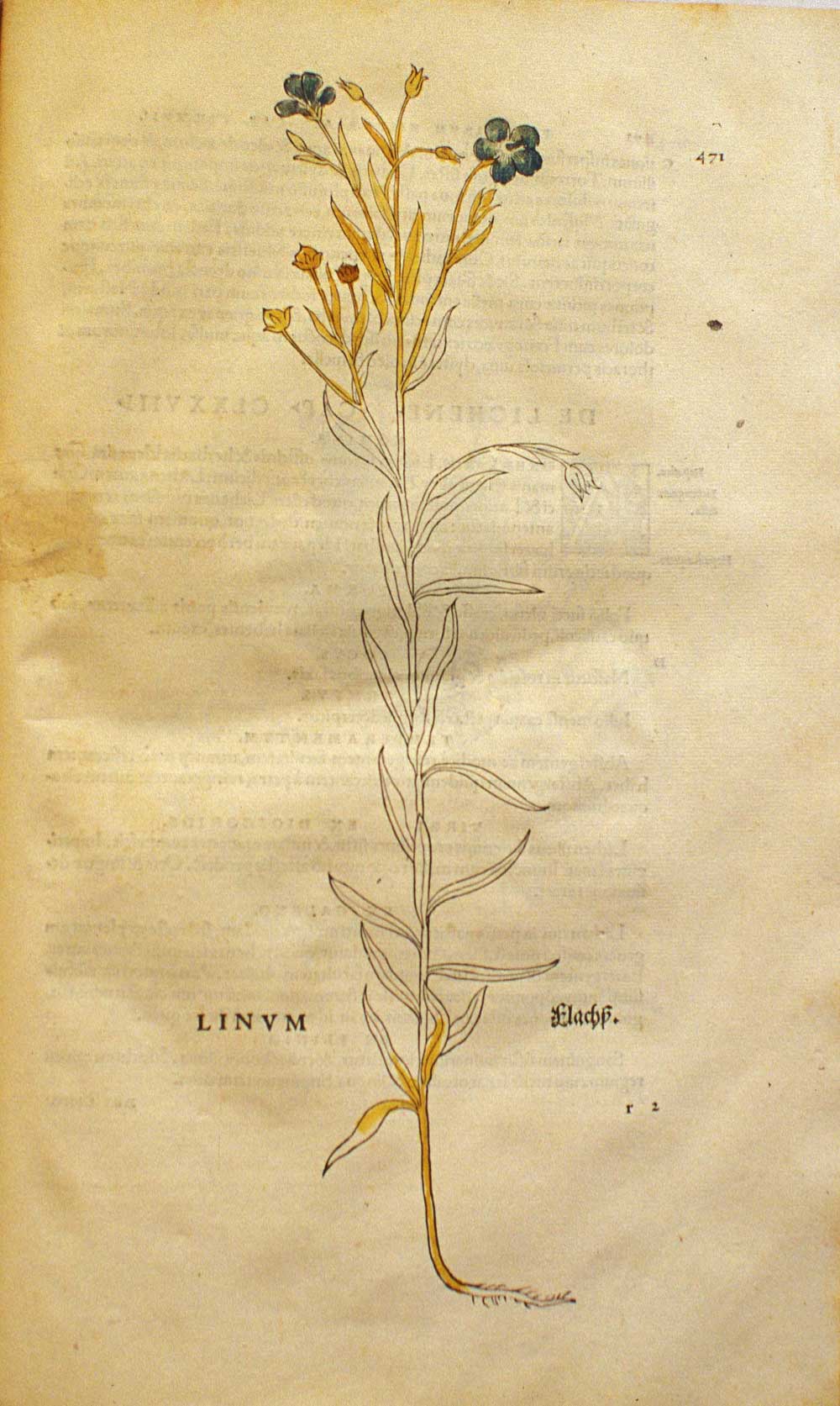

Linum

Linum usitatissimum

Linum usitatissimum L.

English: flax

Linum usitatissimum

Linum usitatissimum L.

English: flax

Linum usitatissimum

Linum usitatissimum L.

Flax, Linen

Flax

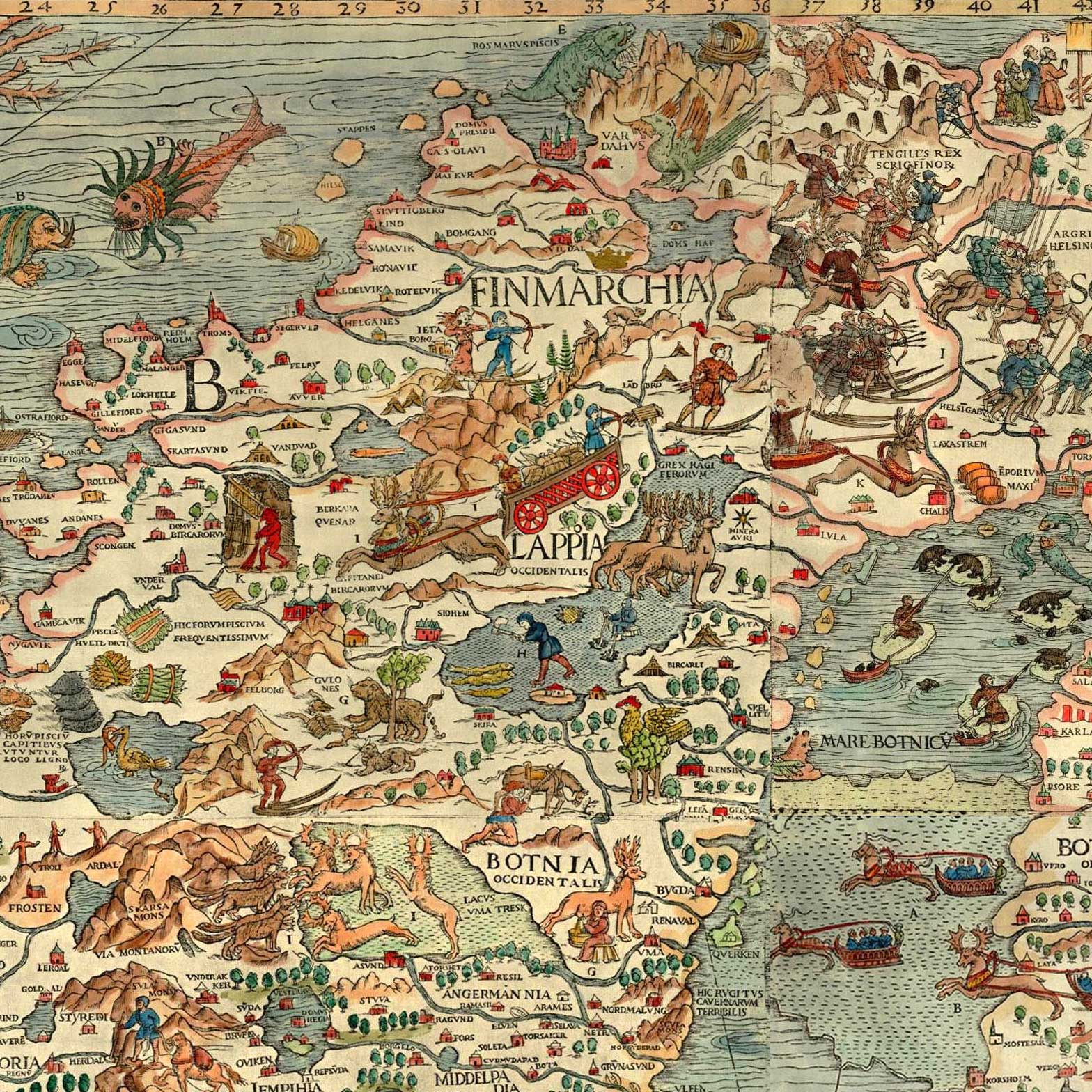

I. An account of the constellations, seasons and weather has now been given that is easy even for non-experts to understand does not leave any room for doubt; and for those who really understand the matter the countryside contributes to our knowledge of the heavens no less than astronomy contributes to agriculture. Many writers have made horticulturea the next subject; we however do not think the time has come to pass straight to those topics, and we are surprised that some persons seeking from these subjects the satisfaction of knowledge, or a reputation for learning, have passed over so many matters without making any mention of all the plants that grow of their own accord or from cultivation, especially in view of the fact that even greater importance attaches to very many of these, in point of price and of practical utility, than to the cereals. And to begin with admitted utilities and with commodities distributed not only throughout all lands but also over the seas: flax is a plant that is grown from seed and that cannot be included either among cereals or among garden plants; but in what department of life shall we not meet with it, or what is more marvellous than the fact that there is a plant which brings Egypt so close to Italy that of two governors of Egypt Galerius reached Alexandria from the Straits of Messina in seven days and Balbillus in six, and that in the summer 15 years later the praetorian senator Valerius Marianus made Alexandria from Pozzuoli in nine days with a very gentle breeze? or that there is a plant that brings Cadiz within seven days’ sail from the Straits of Gibraltar to Ostia, and Hither Spain within four days, and the Province of Narbonne within three, and Africa within two? The last record was made by Gaius Flavius, deputy of the proconsul Vibius Crispus, even with a very gentle wind blowing. How audacious is life and how full of wickedness, for a plant to be grown for the purpose of catching the winds and the storms, and for us not to be satisfied with being borne on by the waves alone, nay that by this time we are not even satisfied with sails that are larger than ships, but, although single trees are scarcely enough for the size of the yard-arms that carry the sails, nevertheless other sails are added above the yards and others besides are spread at the bows and others at the sterns, and so many methods are employed of challenging death, and finally that out of so small a seed springs a means of carrying the whole world to and fro, a plant with so slender a stalk and rising to such a small height from the ground, and that this, not after being woven into a tissue by means of its natural strength but when broken and crushed and reduced by force to the softness of wool, afterwards by this ill-treatment attains to the highest pitch of daring! No execration is adequate for an inventor in navigation (whom we mentioned above in the proper place [Daedalus. See VII. 206]), who was not content that mankind should die upon land unless he also perished where no burial awaits him. Why, in the preceding Book we were giving a warning to beware of storms of rain and wind for the sake of the crops and of our food: and behold man’s hand is engaged in growing and likewise his wits in weaving an object which when at sea is only eager for the winds to blow! And besides, to let us know how the Spirits of Retribution have favoured us, there is no plant that is grown more easily; and to show us that it is sown against the will of Nature, it scorches the land and causes the soil actually to deteriorate in quality.

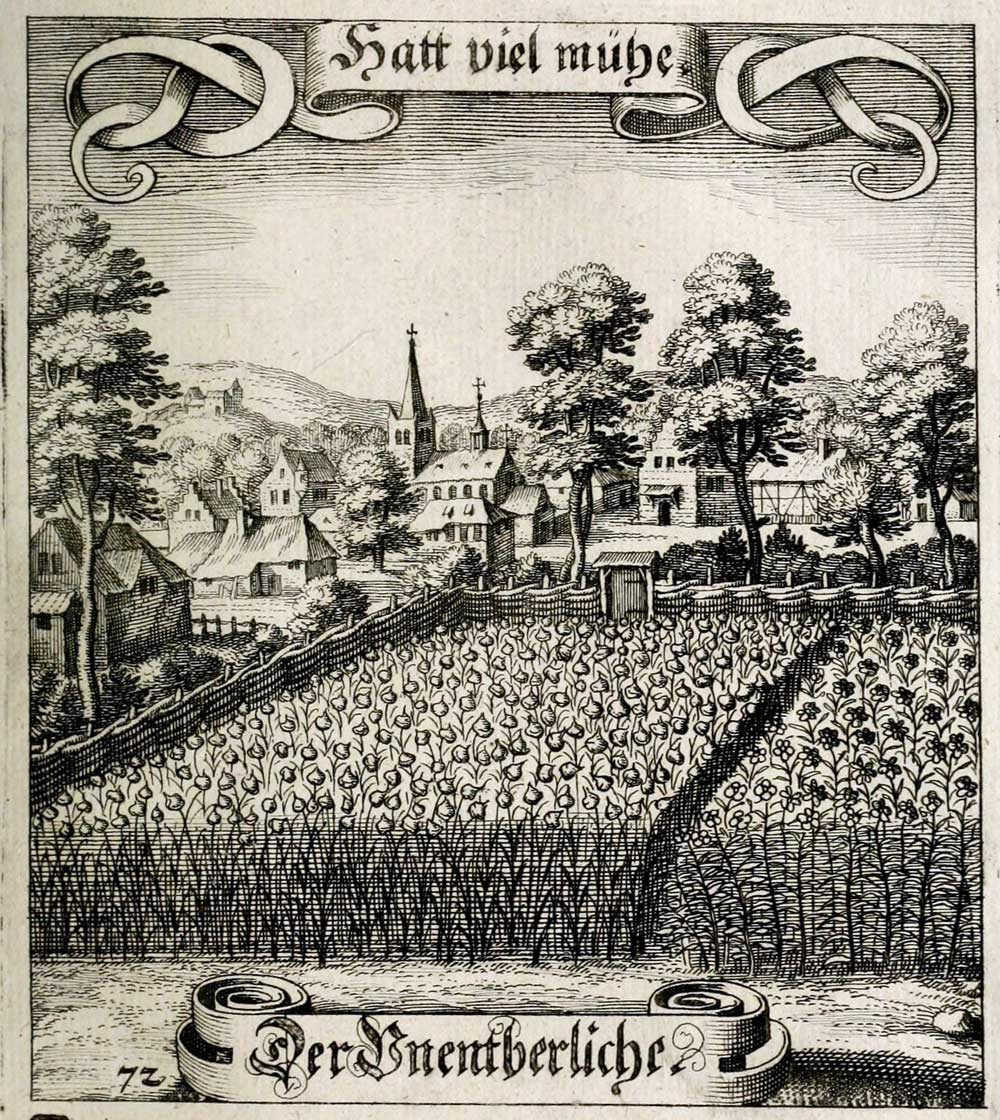

II. Flax is chiefly grown in sandy soils, and with a single ploughing. No other plant grows more quickly: it is sown in spring and plucked in summer, and owing to this also it does damage to the land. Nevertheless, one might forgive Egypt for growing it to enable her to import the merchandise of Arabia and India. Really? And are the Gallic provinces also assessed on such revenue as this? And is it not enough that they have the mountains separating them from the sea, and that on the side of the ocean they are bounded by an actual vacuum [I.e. the Atlantic ocean is mere emptiness, τὸ κενόν of the philosophers] as the term is? The Cadurci, Caleti, Ruteni, Bituriges, and the Morini who are believed to be the remotest of mankind, in fact the whole of the Gallic provinces, weave sailcloth, and indeed by this time so do even our enemies across the Rhine, and linen is the showiest dress-material known to their womankind. This reminds us of the fact recorded by Varro that it is a clan-custom in the family of the Serrani for the women not to wear linen dresses. In Germany the women carry on this manufacture in caves dug underground [The humidity was supposed to be favourable to the manufacture of the tissue]; and similarly also in the Alia district of Italy between the Po and the Ticino, where the linen wins the prize as the third best in Europe, that of Saetabis being first, as the second prize is won by the linens of Retovium near the Alia district and Faenza on the Aemilian Road. The Faenza linens are preferred for whiteness to those of Alia, which are always unbleached, but those of Retovium are supremely fine in texture and substance and are as white as the Faventia, but have no nap, which quality counts in their favour with some people but puts off others. This flax makes a tough thread having a quality almost more uniform than that of a spider’s web, and giving a twang when you choose to test it with your teeth; consequently it is twice the price of the other kinds.

And after these it is Hither Spain that has a linen of special lustre, due to the outstanding quality of a stream that washes the city of Tarragon, in the waters of which it is dressed; also its fineness is marvellous, Tarragon being the place where cambrics were first invented. From the same province of Spain Zoëla flax has recently been imported into Italy, a flax specially useful for hunting-nets; Zoëla is a city of Gallaecia near the Atlantic coast. The flax of Cumae in Campania also has a reputation of its own for nets for fishing and fowling, and it is also used as a material for making hunting-nets: in fact we use flax to lay no less insidious snares for the whole of the animal kingdom than for ourselves! But the Cumae nets will cut the bristles of a boar and even turn the edge of a steel knife; and we have seen before now netting of such fine texture that it could be passed through a man’s ring, with running tackle and all, a single person carrying an amount of net sufficient to encircle a wood! Nor is this the most remarkable thing about it, but the fact that each string of these nettings consists of 150 threads, as recently made for Fulvius Lupus who died in the office of governor of Egypt. This may surprise people who do not know that in a breastplate that belonged to a former king of Egypt named Amasis, preserved in the temple of Minerva at Lindus on the island of Rhodes, each thread consisted of 365 separate threads, a fact which Mucianus, who held the consulship three times quite lately, stated that he had proved to be true by investigation, adding that only small remnants of the breastplate now survive owing to the damage done by persons examining this quality. Italy also values the Pelignian flax as well, but only in its employment by fullers—no flax is more brilliantly white or more closely resembles wool; and similarly the flax grown at Cahors has a special reputation for mattresses: this use of it is an invention of the provinces of Gaul, as likewise is flock. As for Italy, the custom even now survives in the word used for bedding. Egyptian flax is not at all strong, but it sells at a very good price. There are four kinds in that country, Tanitic, Pelusiac, Butic and Tentyritic, named from the districts where they grow. The upper part of Egypt, lying in the direction of Arabia, grows a bush which some people call cotton, but more often it is called by a Greek work meaning ‘wood’: hence the name xylina given to linens made of it. It is a small shrub, and from it hangs a fruit resembling a bearded nut, with an inner silky fibre from the down of which thread is spun. No kinds of thread are more brilliantly white or make a smoother fabric than this. Garments made of it are very popular with the priests of Egypt. A fourth kind is called othoninum; it is made from a sort of reed growing in marshes, but only from its tuft. Asia makes a thread out of broom, of which specially durable fishing-nets are made, the plant being soaked in water for ten days; the Ethiopians and Indians make thread from apples, and the Arabians from gourds that grow on trees, as we said.

III. With us the ripeness of flax is ascertained by two indications, the swelling of the seed or its assuming a yellowish colour. It is then plucked up and tied together in little bundles each about the size of a handful, hung up in the sun to dry for one day with the roots turned upward, and then for five more days with the heads of the bundles turned inward towards each other so that the seed may fall into the middle. Linseed makes a potent medicine; it is also popular in a rustic porridge with an extremely sweet taste, made in Italy north of the Po, but now for a long time only used for sacrifices. When the wheat-harvest is over the actual stalks of the flax are plunged in water that has been left to get warm in the sun, and a weight is put on them to press them down, as flax floats very readily. The outer coat becoming looser is a sign that they are completely soaked, and they are again dried in the sun, turned head downwards as before, and afterwards when thoroughly dry they are pounded on a stone with a tow-hammer. The part that was nearest the skin is called oakum—it is flax of an inferior quality, and mostly more fit for lampwicks; nevertheless this too is combed with iron spikes until all the outer skin is scraped off. The pith has several grades of whiteness and softness, and the discarded skin is useful for heating ovens and furnaces. There is an art of combing out and separating flax: it is a fair amount for fifteen . . [The text seems defective, a plural noun having been lost] to be carded out from fifty pounds’ weight of bundles; and spinning flax is a respectable occupation even for men. Then it is polished in the thread a second time, after being soaked in water and repeatedly beaten out against a stone, and it is woven into a fabric and then again beaten with clubs, as it is always better for rough treatment.

IV. Also a linen has now been invented that is incombustible. It is called ‘live’ linen, and I have seen napkins made of it glowing on the hearth at banquets and burnt more brilliantly clean by the fire than they could be by being washed in water. This linen is used for making shrouds for royalty which keep the ashes of the corpse separate from the rest of the pyre. The plant [It is really the mineral asbestos] grows in the deserts and sun-scorched regions of India where no rain falls, the haunts of deadly snakes, and it is habituated to living in burning heat; it is rarely found, and is difficult to weave into cloth because of its shortness; its colour is normally red but turns white by the action of fire. When any of it is found, it rivals the prices of exceptionally fine pearls. The Greek name for it is asbestinon [‘Inextinguishable’], derived from its peculiar property. Anaxilaus states that if this linen is wrapped round a tree it can be felled without the blows being heard, as it deadens their sound. Consequently this kind of linen holds the highest rank in the whole of the world. The next place belongs to a fabric made of fine flax grown in the neighbourhood of Elis in Achaia, and chiefly used for women’s finery; I find that it formerly changed hands at the price of gold, four denarii for one twenty-fourth of an ounce. The nap of linen cloths, principally that obtained from the sails of sea-going ships, is much used as a medicine, and its ash has the efficacy of metal dross. Among the poppies also there is a kind from which an outstanding material for bleaching linen is extracted.

V. An attempt has been made to dye even linen so as to adapt it for our mad extravagance in clothes. This was first done in the fleets of Alexander the Great when he was voyaging on the river Indus, his generals and captains having held a sort of competition even in the various colours of the ensigns of their ships; and the river banks gazed in astonishment as the breeze filled out the bunting with its shifting hues. Cleopatra had a purple sail when she came with Mark Antony to Actium, and with the same sail she fled. A purple sail was subsequently the distinguishing mark of the emperor’s ship.

VI. Linen cloths were used in the theatres as awnings, a plan first invented by Quintus Catulus when dedicating the Capitol. Next Lentulus Spinther is recorded to have been the first to stretch awnings of cambric in the theatre, at the games of Apollo. Soon afterwards Caesar when dictator stretched awnings [49–44 b.c.] over the whole of the Roman Forum, as well as the Sacred Way from his mansion, and the slope right up to the Capitol, a display recorded to have been thought more wonderful even than the show of gladiators which he gave. Next even when there was no display of games Marcellus the son of Augustus’s sister Octavia, during his period of office as aedile, in the eleventh consulship of his uncle, from the first of [23 b.c.] August onward fixed awnings of sailcloth over the forum, so that those engaged in lawsuits might resort there under healthier conditions: what a change this was from the stern manners of Cato the ex-censor, who had expressed the view that even the forum ought to be paved with sharp pointed stones [In order to discourage loitering there]! Recently awnings actually of sky blue and spangled with stars have been stretched with ropes even in the emperor Nero’s amphitheatres. Red awnings are used in the inner courts of houses and keep the sun off the moss growing there; but for other purposes white has remained persistently in favour. Moreover as early as the Trojan war linen already held a place of honour—for why should it not be present even in battles as it is in shipwrecks? Homer [Il. II. 529, 830] testifies that warriors, though only a few, fought in linen corslets. This material was also used for rigging ships, according to the same author as interpreted by the more learned scholars, who say that the word sparta used by Homer means ‘sown’.

linen

linen [Old English línen, linnen formed on *lIînom flax.]

Made of flax. †linen wings = sails.

C. 700 The Epinal Glossay Latin and Old English. 1081 Linnin ryhae.

C. 897 K. Ælfred, translator Gregory’s pastoral care xiv. 82 Ðæt hræ&asg.l wæs beboden ðæt sceolde bion &asg.eworht of… twispunnenum twine linenum. C.

1160 Hatton Gospel John xix. 40 Hyo… be-wunden hine mid linene claðe.

A. 1225 Ancren riwle 418 Nexst fleshe ne schal mon werien no linene cloð.

1297 R. Glouc. (Rolls) 8962 Þis gode mold… gurde aboute hire middel a uair linne [v.r. linnene] ssete.

1340 Ayenb. 236 Linene kertel erþan hi by huyte ueleziþe him be-houeþ þet he by ybeate and y-wesse.

1375 Barbour Bruce xiii. 422 Thai… lynyng clothis had, but mair.

C. 1375 Scotch Leg. Saints vii. (Jacobus Minor) 59 Lenyne clath he oysit ay.

1413 Pilgr. Sowle (Caxton) i. i. (1859) 1 She kevered it lappyng [it] in a clene lynnen clothe.

1466 Paston Lett. II. 270 For grey lynen cloth and sylk frenge for the hers.

1508 Dunbar Flyting w. Kennedie 224, I se him want ane sark, I reid 3ow, cummer, tak in your lynning clais.

1535 Coverdale Ezek. xliv. 18 They shal haue fayre lynnynge bonettes vpon their heades.

1571 Grindal Injunc. at York B iij, A comely and decent table,… with a faire linen clothe to lay vpon the same.

C. 1620 Fletcher & Massinger Trag. Barnavelt v. iii, Who Unbard the Havens that the floating Merchant, Might clap his lynnen wings up to the windes.

Cloth woven from flax. The explanation `cloth woven from flax or hemp’, given by Johnson and copied in most subsequent Dicts., appears to be a mere blunder, founded on occasional loose uses.

1362 William Langland The vision of William concerning Piers Plowman A. i. 3 A louely ladi on leor In linnene I-cloþed.

1377 William Langland The vision of William concerning Piers PlowmanB. Prol. 219 Wollewebsteres and weueres of lynnen.

C. 1450 Capgrave Chron. (Rolls) 62 In this same tyme was Linus Pope, whech ordeyned that women schuld with lynand cure her heer.

C. 1460 J. Russell Bk. Nurture 935 Looke þer be blanket cotyn or lynyn to wipe þe neþur ende.

1513 Bradshaw St. Werburge i. 2540 She neuer ware lynon by day or by nyght.

1535 Coverdale 1 Sam. ii. 18 The childe was gyrded with an ouer body cote of lynnen.

1557 New Testament (Geneva) Luke xvi. 19 There was a certayne ryche man we was clothed in purple and fyne lynnen.

1596 Dalrymple tr. Leslie’s Hist. Scot. i. 93 Of linnine lykwyse thay maid wyd sarkis.

1695 Lond. Gaz. No. 3099/2 An Act for Burying in Scotch Linnen.

1747 Wesley Prim. Physic (1762) 69 Apply a Suppository of Linnen.

fossil linen

fossil linen: a kind of asbestos. Obsolete

1797 Encyclopædia Britannica (ed. 3) X. 83/2 Fossile Linen is a kind of amianthus, which consists of flexible, parallel, soft fibres,… celebrated for the uses to which it has been applied, of being woven, and forming an incombustible… .

flax

flax. sb. Forms: flæx, fleax, flex, vlexe, flexe, flaxe, flacks, flax.

[Latin plectere, Greek plekein. Some think however that the root is flah- (:-Old Aryan *plak-) as in flay v., the etymological notion being connected with the process of `stripping’, by which the fibre is prepared.]

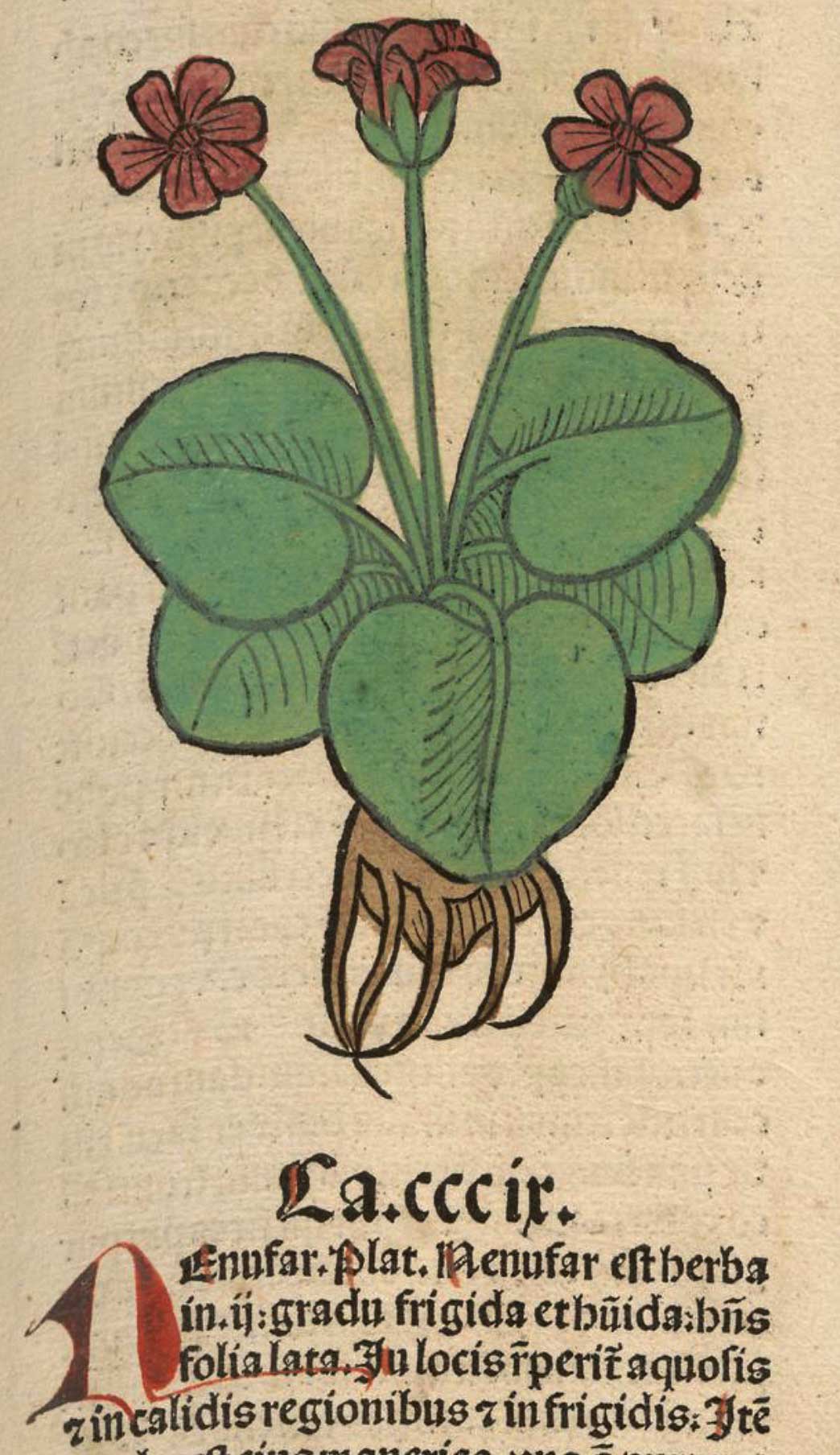

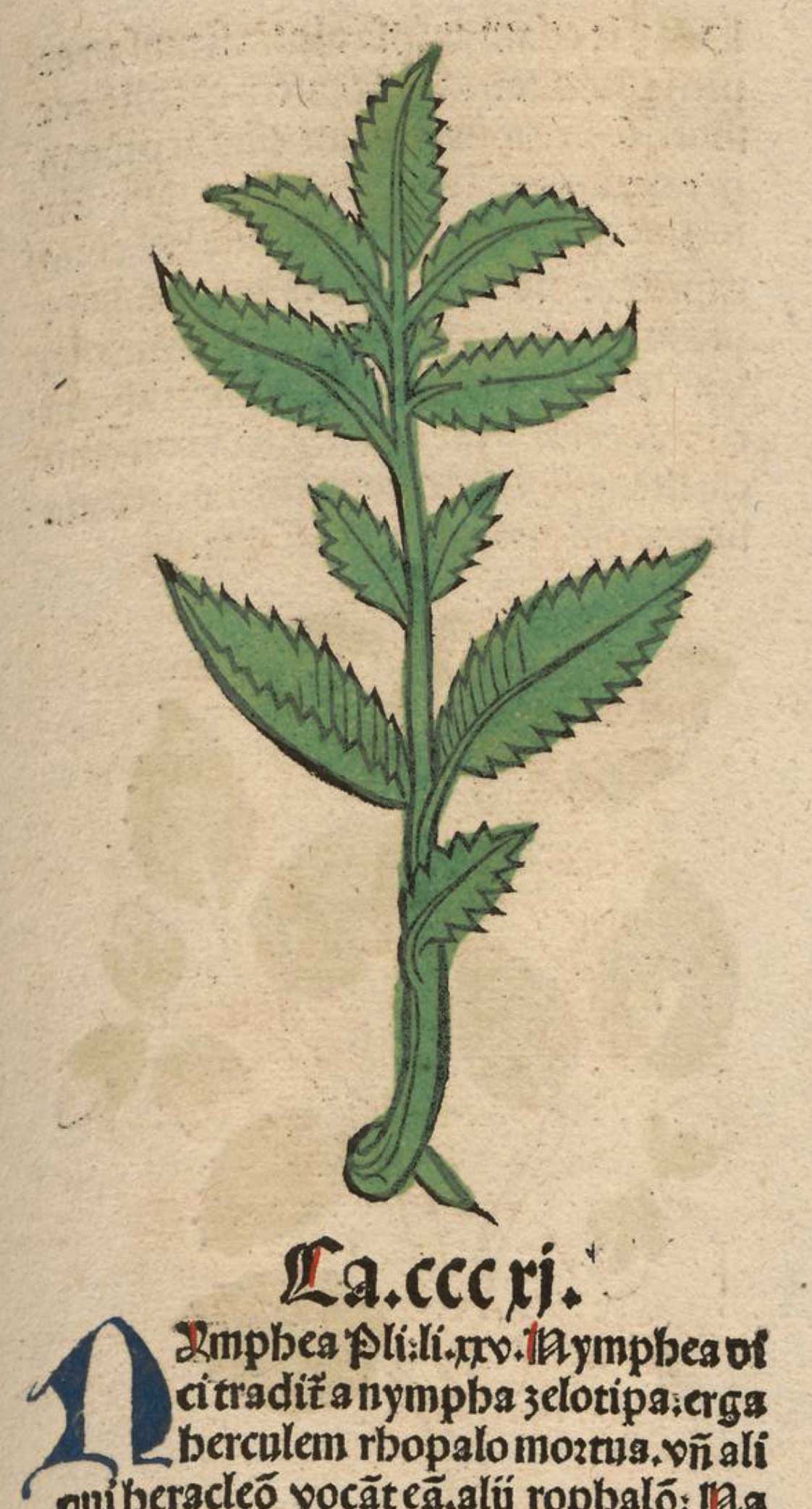

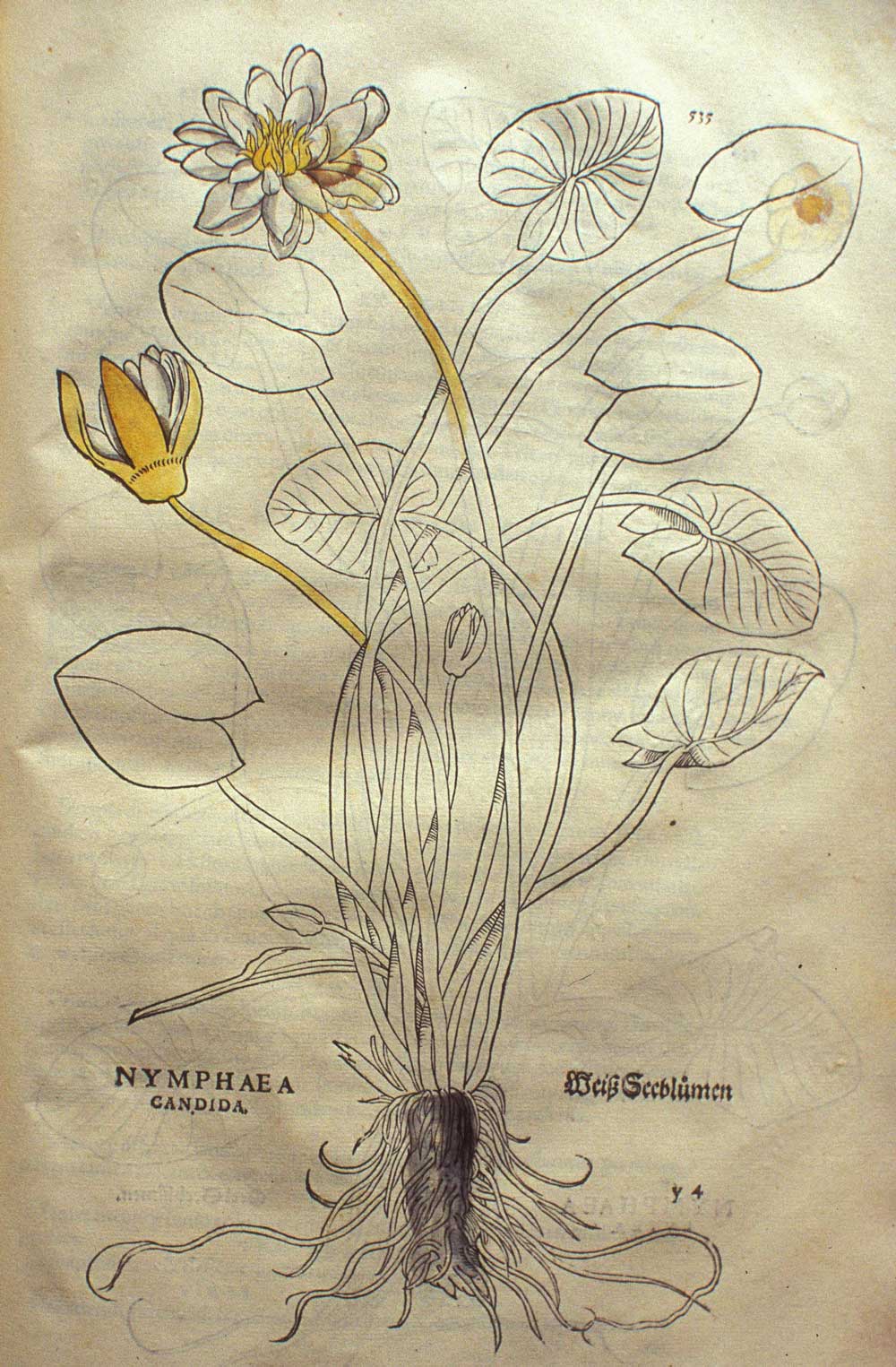

The plant Linum usitatissimum bearing blue flowers which are succeeded by pods containing the seeds commonly known as linseed. It is cultivated for its textile fibre and for its seeds.

C. 1000 Ælfric Exodus. ix. 31 Witodlice eall hira flex and hira bernas wæron fordone.

1398 John de Trevisa Bartholomeus De proprietatibus rerus xvii. xcvii. (Tollem. MS.), Flexe groweþ in euen stalkes, and bereþ 3elow floures or blewe.

1484 William Caxton Fables of Æsop i. xx. Whanne the flaxe was growen and pulled vp.

1562 William Turner A new herball, the seconde parte ii. 39 b, Flax… is called of the Northen men lynt.

1677 Yarranton Engl. Improv. 47 The Land there for Flax is very good, being rich and dry.