Original French: Naſturtium, qui eſt Cresson Alenoys:

Modern French: Nasturtium, qui est Cresson Alenoys:

Notes

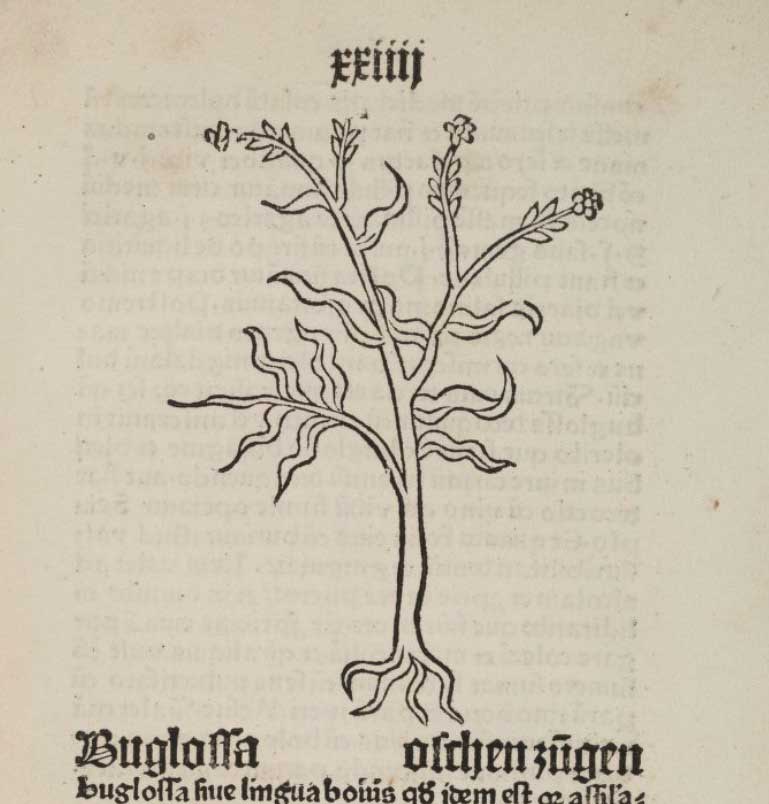

Nasturcium

Schöffer, Peter (ca. 1425–ca. 1502),

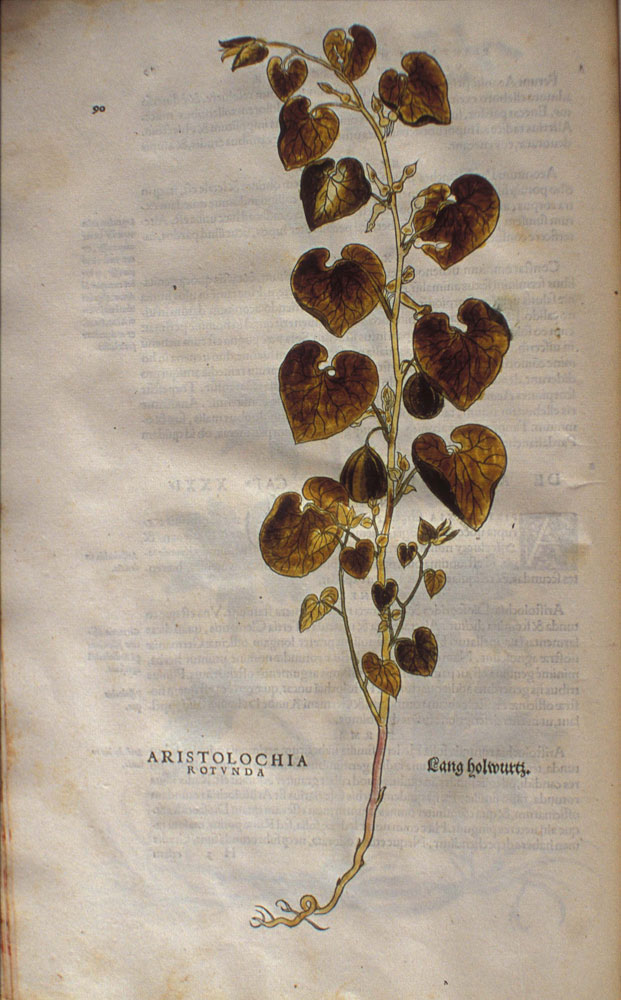

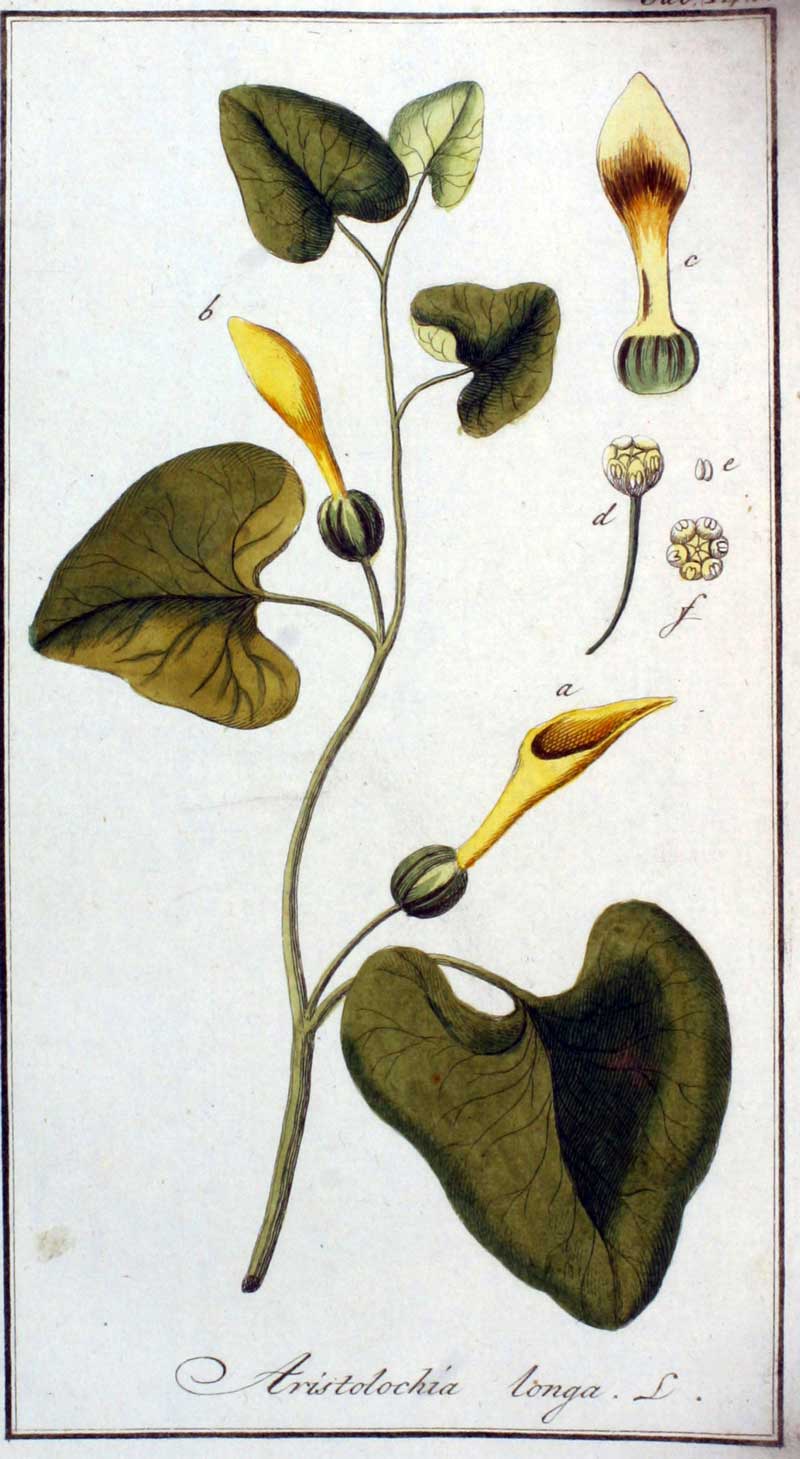

[R]ogatu plurimo[rum] inopu[m] num[m]o[rum] egentiu[m] appotecas refuta[n]tiu[m] occasione illa, q[uia] necessaria ibide[m] ad corp[us] egru[m] specta[n]tia su[n]t cara simplicia et composita. Mainz: 1484.

Botanicus

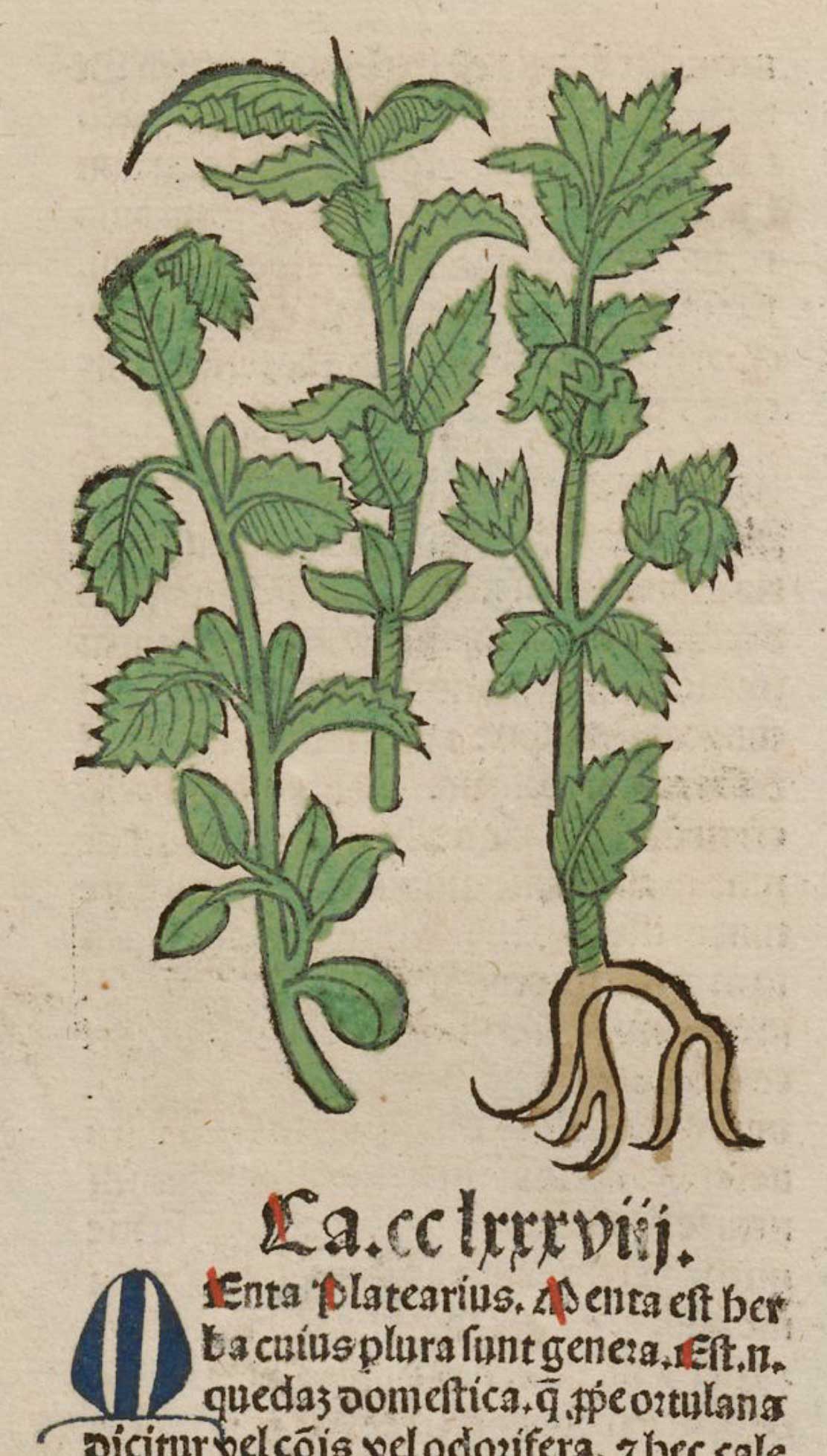

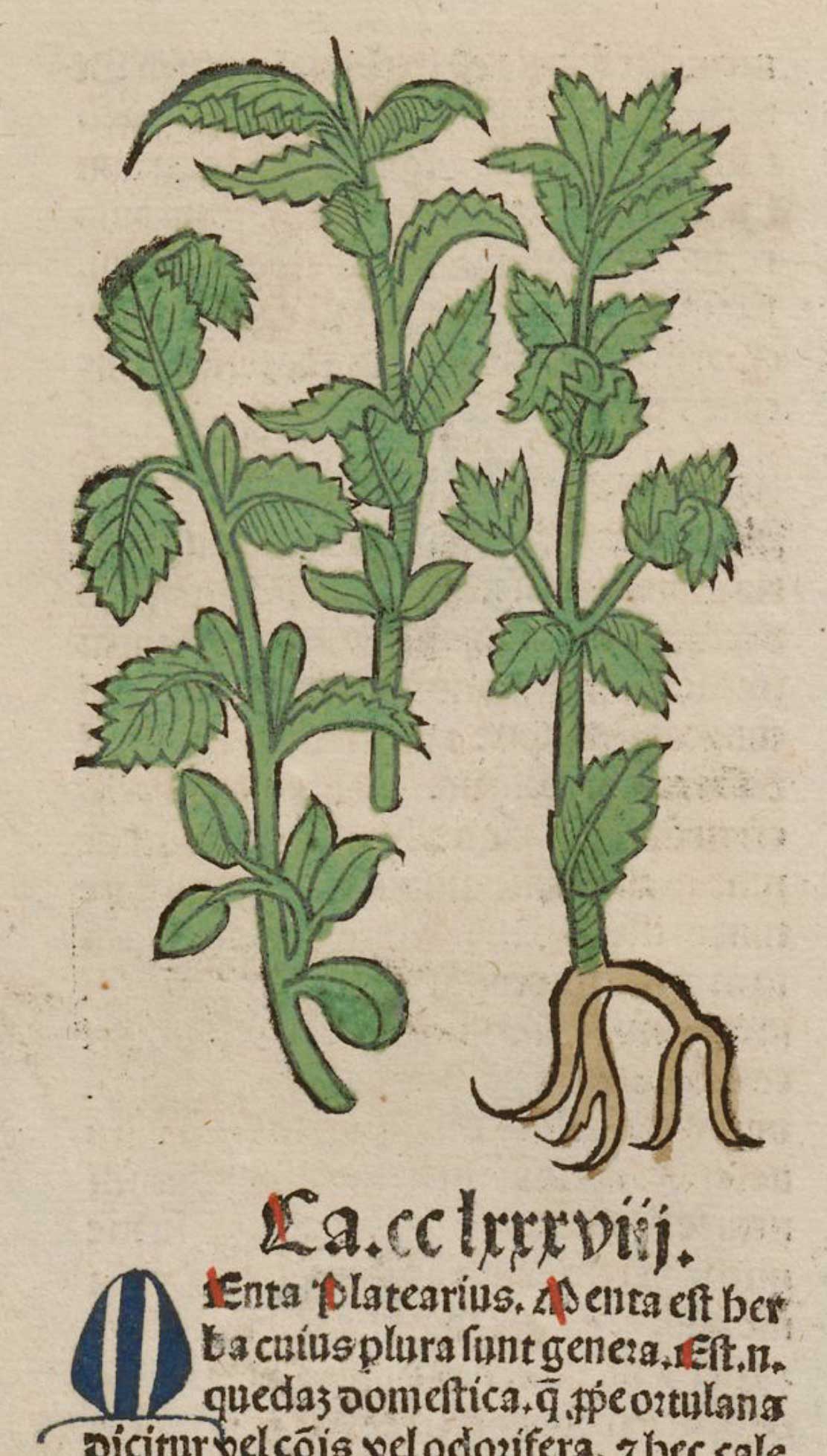

Menta platearius

Nasturcium

nasturtium

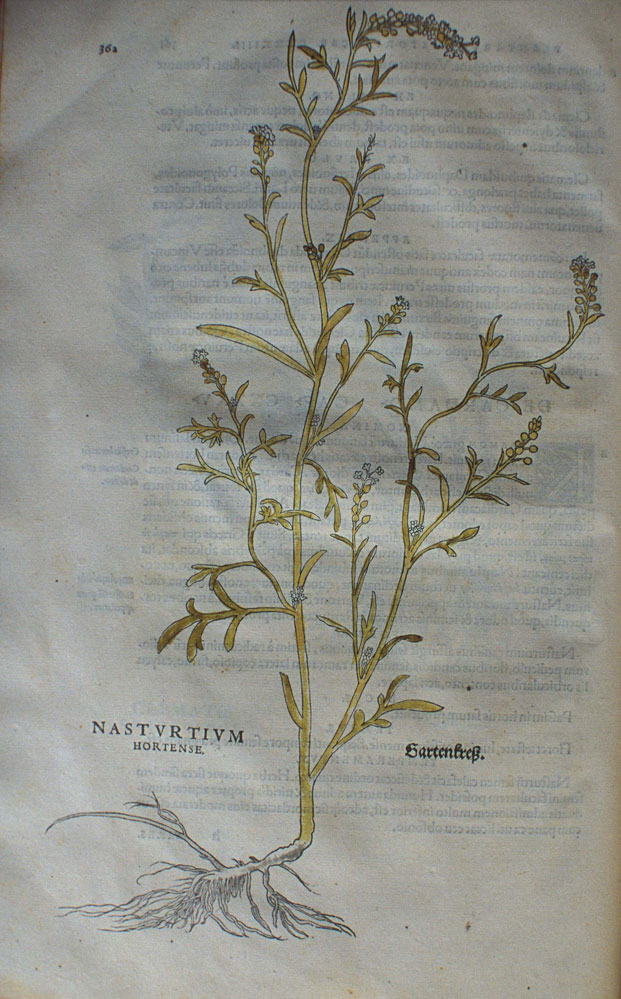

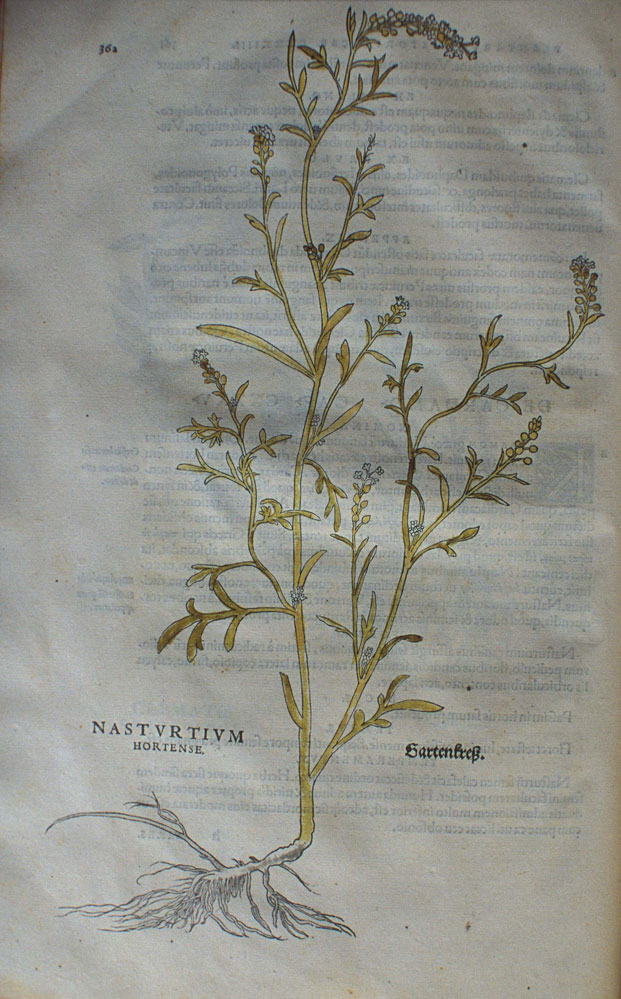

Nasturtium hortense

Gartenkress

Taxon: Lepidium sativum L.

Ancient Greek: kardamon

English: garden cress

Fuchs, Leonhart (1501 – 1566),

De historia stirpium commentarii insignes…. Basil: In Officina Isingriniana, 1542.

Smithsonian Library

nasturtium

nasturtium nomen accepit a narium tormento, et inde vigoris significatio proverbio usurpavit id vocabulum veluti torporem excitantis. in Arabia mirae amplitudinis dicitur gigni.

Cress has got its Latin name [Nasturtium = ‘nostril-tormenter’, from naris and torqueo] from the pain that it gives to the nostrils, and owing to this the sense of vigorousness has attached itself to that word in the current expression [Ἔσθιε κάρδαμον, ‘eat some Cress’, said to sluggish people], as denoting a stimulant. It is said to grow to a remarkably large size in Arabia.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.44.

Loeb Classical Library

nasturtium

E contrario nasturtium venerem inhibet, animum exacuit, ut diximus. duo eius genera. album alvum purgat, detrahit bilem potum X pondere in aquae vii. strumis cum lomento inlitum opertumque brassica praeclare medetur. alterum est nigrius, quod capitis vitia purgat, visum compurgat, commotas mentes sedat ex aceto sumptum, lienem ex vino potum vel cum fico sumptum, tussim ex melle. si cotidie ieiuni sumant. semen ex vino omnia intestinorum animalia pellit, efficacius addito mentastro. prodest et contra suspiria et tussim cum origano et vino dulci, pectoris doloribus decoctum in lacte caprino. panos discutit cum pice extrahitque corpori aculeos et maculas inlitum ex aceto, contra carcinomata adicitur ovorum album. et lienibus inlinitur ex aceto, infantibus vero e melle utilissime. Sextius adicit ustum serpentes fugare, scorpionibus resistere, capitis dolores contrito, alopecias emendari addito sinapi, gravitatem aurium trito inposito auribus cum fico, dentium dolores infuso in aures suco, porriginem concoquit cum fermento. carbunculos ad suppurationem perducit et rumpit, phagedaenas ulcerum expurgat cum melle. coxendicibus et lumbis cum polenta ex aceto inlinitur, item licheni, unguibus scabris, quippe natura eius caustica est. optimum autem Babylonium, silvestri ad omnia ea effectus maior.

On the other hand cress is antaphrodisiac, but as we have already said sharpens the senses. There are two varieties of it. The white acts as a purge, and carries bile away if one denarius by weight of it be taken in seven of water. It is an excellent cure for scrofula if applied with bean meal and covered with a cabbage leaf. The other kind, which is darker, purges away peccant humours of the head, clears the vision, calms if taken in vinegar troubled minds, and benefits the spleen when drunk in wine or eaten with a fig, or a cough if taken in honey, provided that the dose be repeated daily and administered on an empty stomach. The seed in wine expels all parasites of the intestines, more effectively however if there be added wild mint. Taken with wild marjoram and sweet wine it is good for asthma and cough, and a decoction in goat’s milk relieves pains in the chest. Applied with pitch it disperses superficial abscesses; applied in vinegar it extracts thorns from the body and removes spots. When used for carcinoma white of egg is added. It is applied in vinegar to the spleen, but with babies it is best applied in honey. Sextius adds that burnt cress keeps away serpents, and neutralizes scorpion stings; that the pounded plant relieves head-ache, and mange, if mustard be added; that pounded and placed with fig on the ears it relieves hardness of hearing, and toothache if its juice be poured into the ears; and that dandruff and sores on the head are removed if the juice be applied with goose grease. Boils it brings to a head if applied with leaven. It makes carbuncles suppurate and break, and with honey it cleanses phagedaenic ulcers. With pearl barley it is applied in vinegar for sciatica and lumbago, likewise for lichen and rough nails, because its nature is caustic. The best kind, however, is the Babylonian; the wild variety for all the purposes mentioned is the more efficacious.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 6: Books 20–23. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1951. 20.50.

Loeb Classical Library

Alenois

Alenois. Cresson Alenois. Kers, garden cresses, town kars, towne cresses.

Cotgrave, Randle (–1634?),

A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongue. London: Adam Islip, 1611.

PBM

Cresson Alenois

Parmi les Cris de Paris, mis en rime par Guillaume de la Villeneuve, qui est le 117. des Poëtes François mentionnez dans le Recuil de Fauchet, on lit: voez cy Creſſon Orlenois; & dans Froiſſart, vol. 2. chap. 161 l’Orléanois eſt appelé Orlenois.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Œuvres de Maitre François Rabelais. Publiées sous le titre de : Faits et dits du géant Gargantua et de son fils Pantagruel, avec la Prognostication pantagrueline, l’épître de Limosin, la Crême philosophale et deux épîtres à deux vieilles de moeurs et d’humeurs différentes. Nouvelle édition, où l’on a ajouté des remarques historiques et critiques. Tome Troisieme. Jacob Le Duchat (1658–1735), editor. Amsterdam: Henri Bordesius, 1711. p. 258.

Google Books

cresson alenois

Parmi les Cris de Paris, mis en rime par Guillaume de La Villeneuve, qui est le cent-dix-septième des poëts françois mentionnez dans la recueil de Fauchet, on lit veez cy cresson orlenois; et dans Froissart, vol. II, chap. CLXI, l’Orléanois est appelé Orlénois. (L.)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Œuvres de Rabelais (Edition Variorum). Tome Cinquième. Charles Esmangart (1736–1793), editor. Paris: Chez Dalibon, 1823. p. 269.

Google Books

Alenoir

Alenoir, allée, passage, chemin, galerie crénelée.

Godefroy, Frédéric (1826–97),

Dictionaire de l’ancienne langue Française. Et du tous ses dialectes du IXe au XVe Siècle. Paris: Vieweg, Libraire-Éditeur, 1881-1902.

Lexilogos – Dictionnaire ancien français

Nasturtium

“Nomen accipit a narium tormento” (Pliny xix. 8, § 44).

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

nasturtium

Nasturtium, de nasus torsus, parce que sa saveur âcre fait froncer les ailes du nez. «Nomen accepit a narium tormento,» dit Pline, XIX, 44, qui parle encore du nasturtium au l. XX, ch. 50. — En langue d’oc, nasitord (Duschesne, 1544) ou, par corruption, nasicord (1536). Le cresson alénois est Lepidium sativum, L. Le nom de nasturtium a été transféré par la nomenclature moderne au cresson de fontaine, Nasturtium officinale, R. Br. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 352.

Internet Archive

nasturtium

thus nasturtium, derived from nasus torsus or twisted nose, because its scent causes nasal gymnastics (in France it is called nostrilcress)…

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Complete works of Rabelais. Jacques LeClercq (1891–1971), translator. New York: Modern Library, 1936.

nommés pas leurs vertus et operations

Sauf pour le lichen, tous les détails sont dans De latinis nominibus («Alysson … dicitur (ut ait Galenus) quod mirifice morsus a cane rabido curet. [gk] enim rabiem significat. Ephemerium… quo die sumptum fuerit (ut nominis ipsa ratio ostendit) intermit. Bechion autem appellatum est, quod [gk], id es tusses … juvet. Nasturtium, cresson alenois … dicitur a torquendis naribus. Hyoscame, faba suis, vulgo hannebane, … dicitur … quot pastu ejus convellantur sues ». R. a mal lu ses notes, faisant de hanebanes une plante différente de l’hyoscame.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Le Tiers Livre. Edition critique. Michael A. Screech (b. 1926), editor. Paris-Genève: Librarie Droz, 1964.

Nasturtium

Nasitord, qui fait froncer le nez par son odeur (Pline, XIX, xliv, et XX, l).

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Œuvres complètes. Mireille Huchon, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1994. p. 504, n. 16.

cress

cress. Forms: cresse, cerse, cærse, kerse, arse, crasse, kers, cres, cresse, kars, karsse, cress [OE. cresse, cerse = OLG. *kressa fem., MDutch, MLG. kerse, Dutch kers (also MLG. karse, LG. (Bremen) kasse), Old High German chressa formed on (chresso m.), Middle High German and modern German kresse, apparently of native origin: -Old Teutonic *krasjôn, from root of Old High German chresan to creep, as if `creeper’. The Danish karse, Swedish krasse, Norweigan kars, Lettish kresse, Russian kress, appear to be adopted from German. The synonymous Romanic words, Italian crescione, French cresson, Picard kerson, Catalan crexen, medieval Latin crissonus (9th century Littré) are generally held to be from German, though popularly associated with Latin crescere to grow (as if from a Latin type crescion-em) with reference to the rapid growth of the plant.]

The common name of various cruciferous plants, having mostly edible leaves of a pungent flavour. (Until 19th c. almost always in pleural; sometimes construed with a verb in the singular.) Specifically garden cress, Lepidium sativum, or watercress, Nasturtium officinale.

C. 1000 Saxon Leechdoms, Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England I. 116 Ðeos wyrt… þe man nasturcium, & oðrum naman cærse nemneð.

C. 1000 Saxon Leechdoms. II. 68 Do earban to and cersan and smale netelan and beowyrt.

1393 William Langland The vision of William concerning Piers Plowman ix. 322 With carses [v.r. crasses, cresses] and oþer herbes.

C. 1420 Palladius on husbondrie ii. 218 Now cresses sowe.

C. 1450 Alphita (Anecd. Oxon.) 39 Cressiones, gall. cressouns, anglice cressen.

1533 Sir Thomas Elyot The castel of helth (1541) 9 b, Onyons, Rokat, Karses [1561 Kersis].

1548 William Turner The names of herbes in Greke, Latin, Englische, Duche, and Frenche 55 Nasturtium is called… in englishe Cresse or Kerse.

1578 Henry Lyte, translator Dodoens’ Niewe herball or historie of plantes v. lix. 623 Cresses are commonly sowen in all gardens.

1664 John Evelyn Kalendarium hortense> (1729) 195 Sow also Carrots, Cabbages, Cresses, Nasturtium.

With defining words, applied to many different cruciferous plants, and occasionally to plants of other Natural Orders resembling cress in flavour or appearance

1578 Henry Lyte, translator Dodoens’ Niewe herball or historie of plantes v. lix. 623 This herbe is called… in English, Cresses, Towne Kars, or Towne Cresses.

1578 Lyte Dodoens v. lxii. 627 There be foure kindes of wilde Cresse, or Thlaspi, the which are not… vnlyke cresse in taste.

1597 John Gerard (or Gerarde) The herball, or general historie of plants, ii. xiv. (1623) 253 Banke Cresses is found in stonie places.

1620 Venner Via Recta vii. 158 Water-Cresse, or Karsse, is… of like nature… as Towne-Karsse is.

nasturtium

nasturtium [adopted from Latin nasturtium, so named, according to Pliny, from its pungency (`nomen accepit a narium tormento’): compare French nasitort.]

A genus of cruciferous plants having a pungent taste, of which the best-known representative is the Watercress (N. officinale); also, a plant belonging to this genus.

1570 John Foxe, Acts and monuments of these latter and perillous dayes 1156/2 This was some mery deuill, or els had eaten with his teeth some Nasturcium before.

1602 R. T. Five Godlie Sermons 101 The Nasturcium of the Persians… I take to be a more precious and soueraigne plant than our common Cresses, although it be vulgarly deemed the same.

1664 John Evelyn Kalendarium hortense (1729) 195 Sow also… Cabbages, Cresses, Nasturtium, Fennel [etc.].

1696 Edward Phillips The new world of English words (ed. 5), Nasturtium, the name of a Plant, otherwise called Nosesmart, or Cresses.

1837 Wheelwright, translator Aristophanes II. 261 What prat’st thou of nasturtiums?