Original French: Telephium, de Telephus:

Modern French: Telephium, de Telephus:

Notes

Millefolium

Telephium

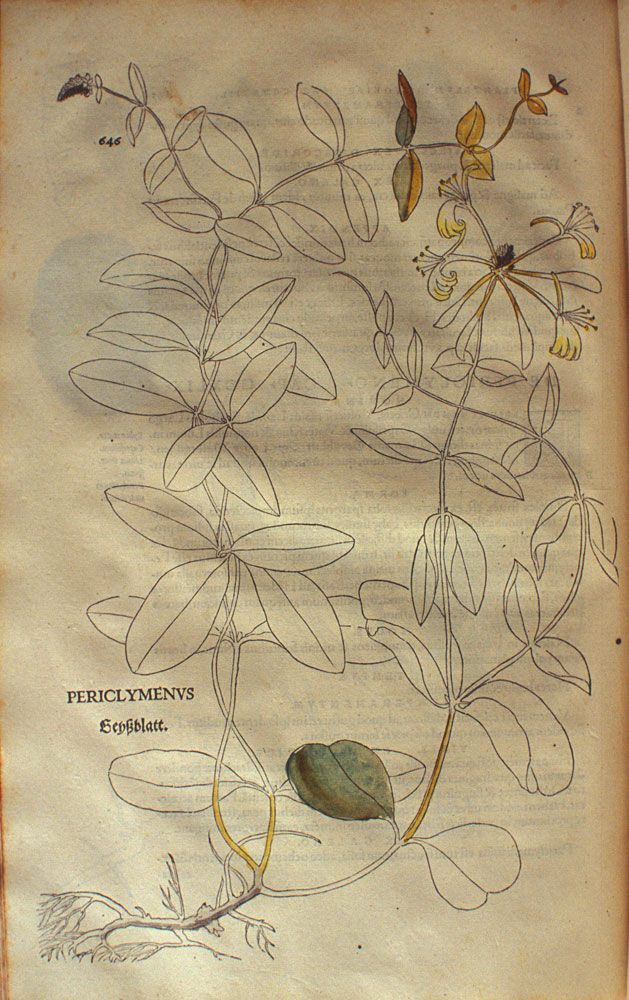

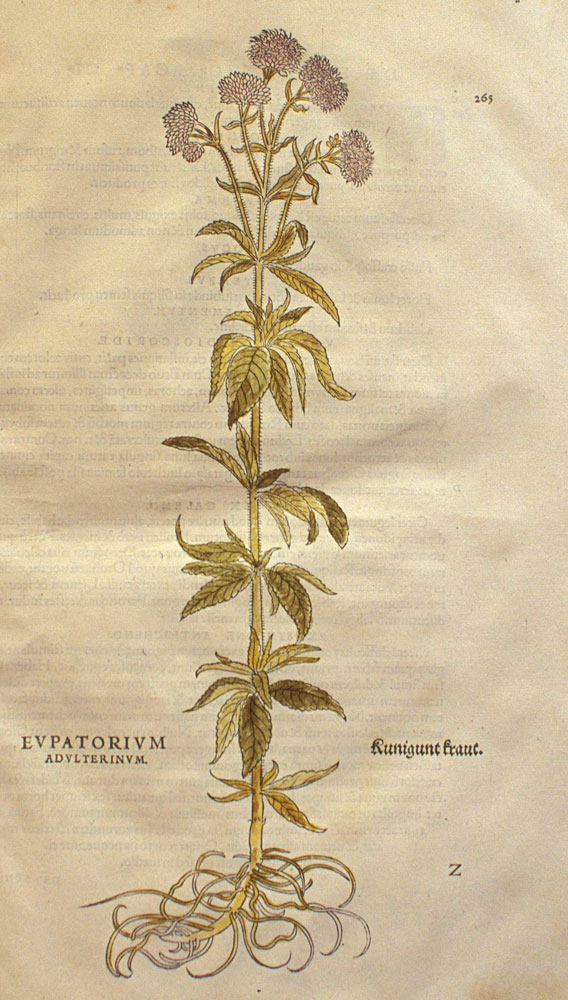

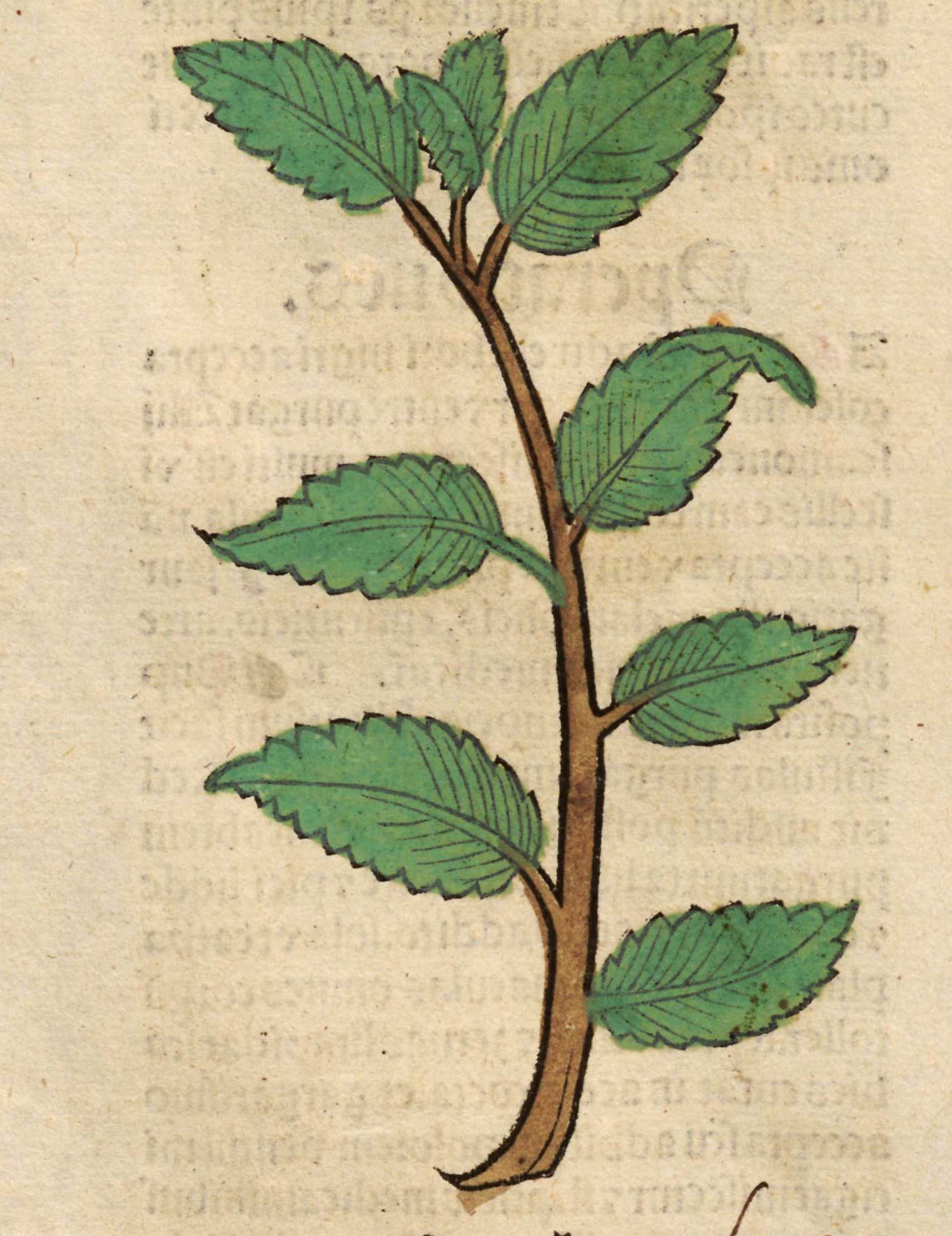

Plate caption: Telephium purpurascens

Wundkraut mennle

Sedum telephium L. ssp. telephium

English: orpine

Fuchs, Leonhart (1501 – 1566),

De historia stirpium commentarii insignes…. Basil: In Officina Isingriniana, 1542.

Smithsonian Library

telephium

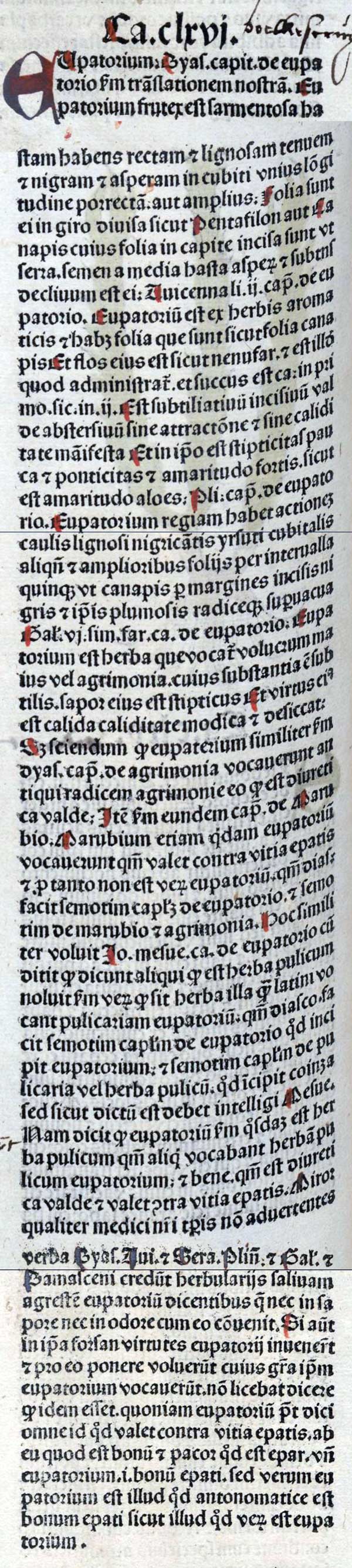

Invenit et Achilles discipulus Chironis qua volneribus mederetur. quae ob id achilleos vocatur. hac sanasse Telephum dicitur. alii primum aeruginem invenisse utilissimam emplastris, ideoque pingitur ex cuspide decutiens eam gladio in volnus Telephi, alii utroque usum medicamento volunt. aliqui et hanc panacem Heracliam, alii sideriten et apud nos millefoliam vocant, cubitali scapo, ramosam, minutioribus quam feniculi foliis vestitam ab imo. alii fatentur quidem illam vulneribus utilem, sed veram achilleon esse scapo caeruleo pedali, sine ramis, ex omni parte singulis foliis rotundis eleganter vestitam; alii quadrato caule, capitulis marrubii, foliis quercus, hac etiam praecisos nervos glutinari. faciunt alii et sideritim in maceriis nascentem, cum teratur, foedi odoris, etiamnum aliam similem huic sed candidioribus foliis et pinguioribus, teneriorem cauliculis, in vineis nascentem; aliam vero binum cubitorum, ramulis exilibus, triangulis, folio filicis, pediculo longo, betae semine; omnes volneribus praecipuas. nostri eam quae est latissimo folio scopas regias vocant. medetur anginis suum.

Achilles too, the pupil of Chiron, discovered [By “discovering” a plant Pliny seems to mean discovering its value in medicine] a plant to heal wounds, which is therefore called achilleos, and by it he is said to have cured Telephus. Some have it that he was the first to find out that copper-rust is a most useful ingredient of plasters, for which reason he is represented in paintings as scraping it with his sword from his spear on to the wound of Telephus, while others hold that he used both remedies. This plant is also called by some Heraclean panaces, by others siderites, and by us millefolia; the stalk is a cubit high, and the plant branchy, covered from the bottom with leaves smaller than those of fennel. Others admit that this plant is good for wounds, but say that the real achilleos has a blue stalk a foot long and without branches, gracefully covered all over with separate, rounded leaves. Others describe achilleos as having a square stem, heads like those of horehound, and leaves like those of the oak; they claim that it even unites severed sinews. Some give the name sideritis to another plant, which grows on boundary walls and has a foul smell when crushed, and also to yet another, like this but with paler and more fleshy leaves, and with more tender stalks, growing in vineyards; finally to a third, two cubits high, with thin, triangular twigs, leaves like those of the fern, a long foot-stalk and seed like that of beet. All are said to be excellent for wounds. Roman authorities call the one with the broadest leaf royal broom; it cures quinsy in pigs.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 7: Books 24–27. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1956. 25.019.

Loeb Classical Library

telephium

Telephion porcilacae similis est et caule et foliis. rami a radice septeni octonique fruticant foliis crassis, carnosis. nascitur in cultis et maxime inter vites. inlinitur lentigini et, cum inaruit, deteritur. inlinitur et vitiligini ternis fere mensibus, senis horis noctis aut diei, postea farina hordeacia inlinatur. medetur et vulneribus et fistulis.

Telephion resembles purslane in both stem and leaves. Seven or eight branches from the root make a bushy plant with coarse, fleshy leaves. It grows on cultivated ground, especially among vines. It is used as liniment for freckles and rubbed off when dry; it makes liniment also for psoriasis, to be applied for about three months, six hours each night or day; afterwards barley meal should be applied. It is also good treatment for wounds and fistulas.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 7: Books 24–27. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1956. 27.110.

Loeb Classical Library

Telephium

Pliny xxv 5, § 19. Achilleos, with which Achilles is said to have healed Telephus.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

telephium

Télèphe, fils d’Hercule, fut blessé et guéri par Achille au siège de Troie. « Telephion porcilacæ similis est et caule et foliis », dit Pline, XXVII, 110. Probablement Sedum telephium, L. (Crassulacée). Columna a voulu y voir Zygophyllum fabago, L.; d’autres disent le Cochlearia. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 347.

Internet Archive

telephium

Named for Telephus, son of Hercules, wounded and healed by Achilles at the siege of Troy.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Complete works of Rabelais. Jacques LeClercq (1891–1971), translator. New York: Modern Library, 1936.

Telephium

Fils d’Hercule, blessé et guéri par Achille au siège de Troie.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Œuvres complètes. Mireille Huchon, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1994. p. 503, n. 9.