Author Archives: Swany

pine, from Pitys

Among plants named by metamorphosis of men or women.

In the lore of ancient Greece, Pitys was a nymph. Pitys is mentioned in Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe (ii.7 and 39) and by Lucian of Samosata[1]. Pitys is remembered for her pursuit by Pan, the god of nature and, the folks say, the source of panic. According to a passage in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca (ii.108) she was changed into a pine tree by the gods in order to escape him[2].

1. Lucian (c. AD 125-after 180), Dialogues of the Gods. Thomas Francklin, translator. London: T. Cadell, 1780. 22: Pan and Hermes. Google Books

2. Wikipedia. Wikipedia

Notes

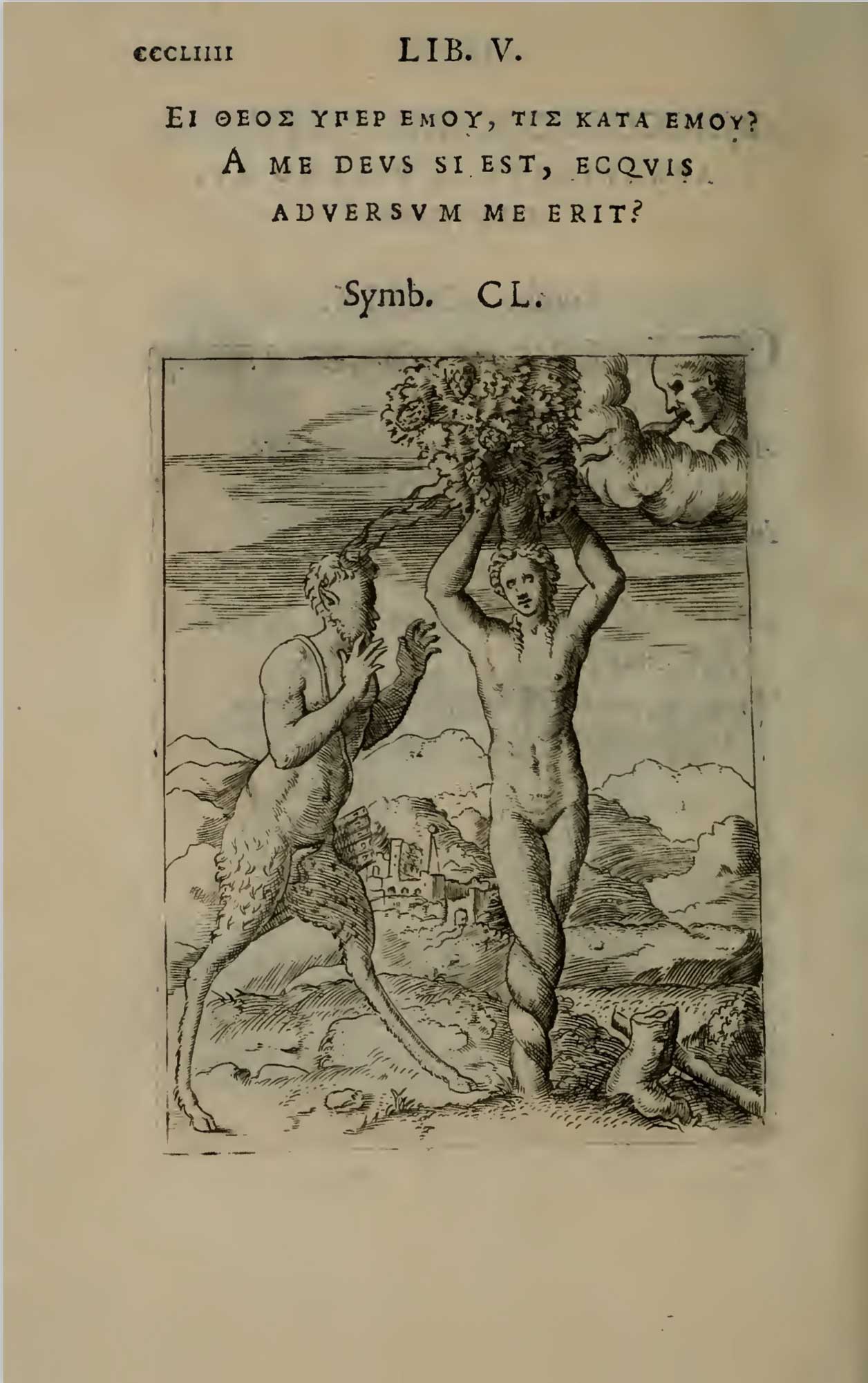

Pan et Pitys

Pan discovering Pitys changed by Boreas into a pine tree

Pitys

10. Baptistae pignae philosopho ferrariensi. Fabella bella pinvs ex pavsania

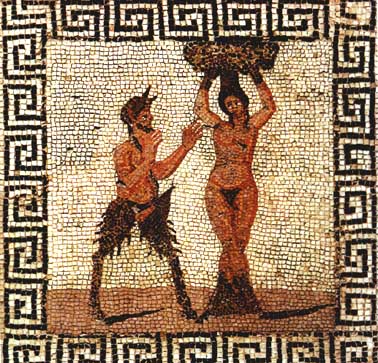

Pan and the nymph Pitys

Il quadretto di Pan e la ninfa Pitys (oppure di Pan e Hamadryade) è un mosaico falso settecentesco (cm 25 x 27), proveniente dalla Collezione napoletana del Duca Carafa di Noja. Si trova attualmente a Napoli nel Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 27708), associato al Gabinetto Segreto. Che si tratti di un falso che non può provenire da una delle antiche città vesuviane lo attesta un’ incisione di Giulio Bonasone (1510-1574) che lo ritrae seppure con qualche semplificazione, e che è conservata al British Museum.

pine

coniferous tree, Old English pin (in compounds), from Old French pin and directly from Latin pinus “pine, pine-tree, fir-tree,” perhaps in reference to the sap or pitch, from PIE *peie– “to be fat, swell” . Compare Sanskrit pituh “juice, sap, resin,” pitudaruh “pine tree,” Greek pitys “pine tree.”

pine (v.)

Old English pinian “to torture, torment, afflict, cause to suffer,” from *pine “pain, torture, punishment,” possibly ultimately from Latin poena “punishment, penalty,” from Greek poine. A Latin word borrowed into Germanic with Christianity. Intransitive sense of “to languish, waste away,” the main modern meaning, is first recorded early 14c.

Pitys

Hermes: Tell me, are you married yet, Pan? Pan’s the name they give you, isn’t it?

Pan: Of course not, daddy. I’m romantically inclined, and wouldn’t like to have to confine my attentions to just one.

Hermes: No doubt, then, you try your luck with the nanny-goats?

Pan: A fine jest coming from you! My lady-friends are Echo and Pitys and all the Maenads of Dionysus, and I’m in great demand with them.

pitys

C’est le nom grec du pin.

Pitys (stone-pine), from Pitys

Lucian, Dial. Deor. 22.

pytis

vos eritis testes, si quos habet arbor amores,

fagus et Arcadio pinus arnica deo

Ye shall be my witnesses, if trees know aught of love,

beech-tree and pine, beloved of Arcady’s god.

Pytis

Pitys, jeune fille poursuivie de Pan et Borée, ayant manifestée quelque inclination pour ce dernier, fut assommée par Pan contre un rocher. La Tere eut compassion de la victime et la changea en Pin. On plaçait sur les bustes de Pan des couronnes de pin. (Lucien, Dial. des deux, XX11.)

Πίτνζ est d’après le Dictionnaire de Planche, le pin ou picéa. D’apres Belon (De arb. conif., f° 16 r° et v°), le picéa est le πενχη des Grecs, et le pinus le πίτνζ. Or, le picea de Belon nous paraît se rapporter soit au pin de Macédoine (Pinus pence, Grisebach) soit aux diverses varietés du Pinus sylvestris, L.; le pinus de Belon, au Pinus pinea, L., ou pin pignon, Mais les opinions botaniques de Rabelais n’étaient peut-être pas les mêmes de Belon, et la confusion est telle, dans la nomenclature ancienne des Conifères, qu’il est difficile de déterminer exactement l’acception, d’ailleurs variable, de ces vieux vocables. (Paul Delaunay)

pitys

thus pitys, or pine, after the maiden of that name who, preferring Boreas to Pan, was dashed against the rocks by the latter, and transmorgified into a tree by the compassionate gods…

pitys

Pitys, Pin. Elle fut changée en arbre par Pan (d’ou le Pinua amata arcadio deo de Properce (I. 18. 29).

Pytis

Jeune fille poursuivie par Pan et Borée, précipitée du haut d’un rocher et transformée en pin par la terre.

par Metamorphose d’hommes et femmes…

Dans son Officina, Ravisius Textor dresse une longue liste des «Mutati in varias formas» ou l’on trouve Daphné, Narcisse, Crocus (safran) et Smilax. L’origine attribuee au myrte est rapportée par les commentateurs de Dioscoride; celle de pitys (le pin), par Lucien, Dial. des dieux, 22,4, et par les Géoponiques, mais aussi par Cœlius Rhodingus, Antiquae Lectiones, XXV, 2. Celle de cinara (l’artichaut) est dans le livre d’Estienne.

Pitys

In Greek mythology— or more particularly in Ancient Greek poetry— Pitys (Πίτυς; English translation: “pine”) was an Oread nymph who was pursued by Pan. According to a passage in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca (ii.108) she was changed into a pine tree by the gods in order to escape him. Pitys is mentioned in Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe (ii.7 and 39) and by Lucian of Samosata (Dialogues of the Dead, 22.4).[1] Pitys was chased by Pan as was Syrinx, who was turned into reeds to escape the satyr who then used her reeds for his panpipes.

These occurrences are noted by Birger A. Pearson, “‘She Became a Tree’: A Note to CG II, 4: 89, 25-26” The Harvard Theological Review, 69.3/4 (July – October 1976): 413-415) p. 414 note 8;

The flute-notes may have frightened the maenads running from his woodland in a “panic.” The subject is illustrated in paintings of (roughly chronologically) Nicolas Poussin, Jacob Jordaens, François Boucher, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Annibale Carracci, Andrea Casali, Arnold Bocklin, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Maxfield Parrish.

Fragment 500783

Others by metamorphosis of the men and women of the same name, like

Original French: Aultres par Metamorphoſe d’homes & femmes de nom ſemblable: comme

Modern French: Aultres par Metamorphose d’hommes & femmes de nom semblable: comme

par Metamorphose d’hommes et femmes…

Dans son Officina, Ravisius Textor dresse une longue liste des «Mutati in varias formas» ou l’on trouve Daphné, Narcisse, Crocus (safran) et Smilax. L’origine attribuee au myrte est rapportée par les commentateurs de Dioscoride; celle de pitys (le pin), par Lucien, Dial. des dieux, 22,4, et par les Géoponiques, mais aussi par Cœlius Rhodingus, Antiquae Lectiones, XXV, 2. Celle de cinara (l’artichaut) est dans le livre d’Estienne.

Le Tiers Livre

Jean Céard, editor

Librarie Général Français, 1995

Fragment 500781

Fragment 500715

Others by the admirable qualities that one sees in them, like

Original French: Les aultres par les admirables qualitez qu’on a veu en elles. comme

Modern French: Les aultres par les admirables qualitez qu’on a veu en elles. comme

par les admirables qualitez

Cf. encore, De latinis nominibus pour tous ces détails. Le seule exemple qui ne s’explique pas de soi-même est hieracia; «Hieracum nomen ex eo venit quod [l’epevier] succo hujus herbae oculorum obscuritatem discutiant». Eryngion (« barbe à bouc ») serait un contrepoison. Que-fait-il dans cette liste?

Le Tiers Livre

Michael A. Screech, editor

Paris-Genève: Librarie Droz, 1964

par les admirables qualitez

Puisés aux mêmes sources, tour ces détails sont clairs. Comme dans la liste précédente, Rabelais termine par des exemples qu’il n’explicite pas. Hieraca, plur. de hieracion, vient de Pline, XX, 7: cette plante passe pour bénéfique aux yeux de l’épervier (dit hierax en grec). L’érynge (eryngion) passe pour exciter à l’amour (Pline, XXII, 8; Manardi, Epistolae medicinales, XII, 4): s’est -on appliqué à y retrouver eros?

Le Tiers Livre

Jean Céard, editor

Librarie Général Français, 1995

Fragment 500713

Fragment 500705

Among the plants named for their virtues and operations.

Notes

Tussilago

Tussilago

Rosshub

Taxon: Tussilago farfara L.

Ancient Greek: bechion

English: coltsfoot

Bechium

“Tussim sedat bechion quae et tussilago dicitur” (Pliny xxvi, 6 § 16).

bechium

Bechion tussilago dicitur. duo eius genera: silvestris ubi nascitur subesse aquas credunt, et hoc habent signum aquileges. folia sunt maiuscula quam hederae quinque aut septem, subalbida a terra, superne pallida, sine caule, sine flore, sine semine, radice tenui. quidam eandem esse arcion et alio nomine chamaeleucen putant. huius aridae cum radice fumus per harundinem haustus et devoratus veterem sanare dicitur tussim, sed in singulos haustus passum gustandum est.

Bechion is also called tussilago. There are two kinds of it. Wherever the wild kind grows it is believed that springs run under the surface, and the plant is considered a sign by the water-finders. The leaves are rather larger than those of ivy, numbering five or seven, whitish underneath and pale on the upper side. There is no stem, or flower, or seed, and the root is slender. Some think it is the same as arcion, and chamaeleuce under another name. The smoke of this plant, dried with the root and burnt, is said to cure, if inhaled deeply through a reed, an inveterate cough, but the patient must take a sip of raisin wine at each inhalation.

Bechium

De βήξ, toux, plante qui calme la toux. «Tussim sedat bechion quæ et tussilago dicitur», dite Pline, XXVI, 16, qui pense pouvoir l’identifier, avec certains auteurs, au chamæleuce, farfarus, or farfugim (XXIV, 85). C’est notre tussilage ou pas d’âne, Tussilago farfara, L. (Paul Delaunay)

bechium

thus bechium or coltsfoot, from Bys a cough, employed in throat ailments…

nommés pas leurs vertus et operations

Sauf pour le lichen, tous les détails sont dans De latinis nominibus («Alysson … dicitur (ut ait Galenus) quod mirifice morsus a cane rabido curet. [gk] enim rabiem significat. Ephemerium… quo die sumptum fuerit (ut nominis ipsa ratio ostendit) intermit. Bechion autem appellatum est, quod [gk], id es tusses … juvet. Nasturtium, cresson alenois … dicitur a torquendis naribus. Hyoscame, faba suis, vulgo hannebane, … dicitur … quot pastu ejus convellantur sues ». R. a mal lu ses notes, faisant de hanebanes une plante différente de l’hyoscame.

Bechium

De βήζ, « toux », tussilage (Pline, XXVI, xvi)

Ephemerum

Among the plants named for their virtues and operations.

Notes

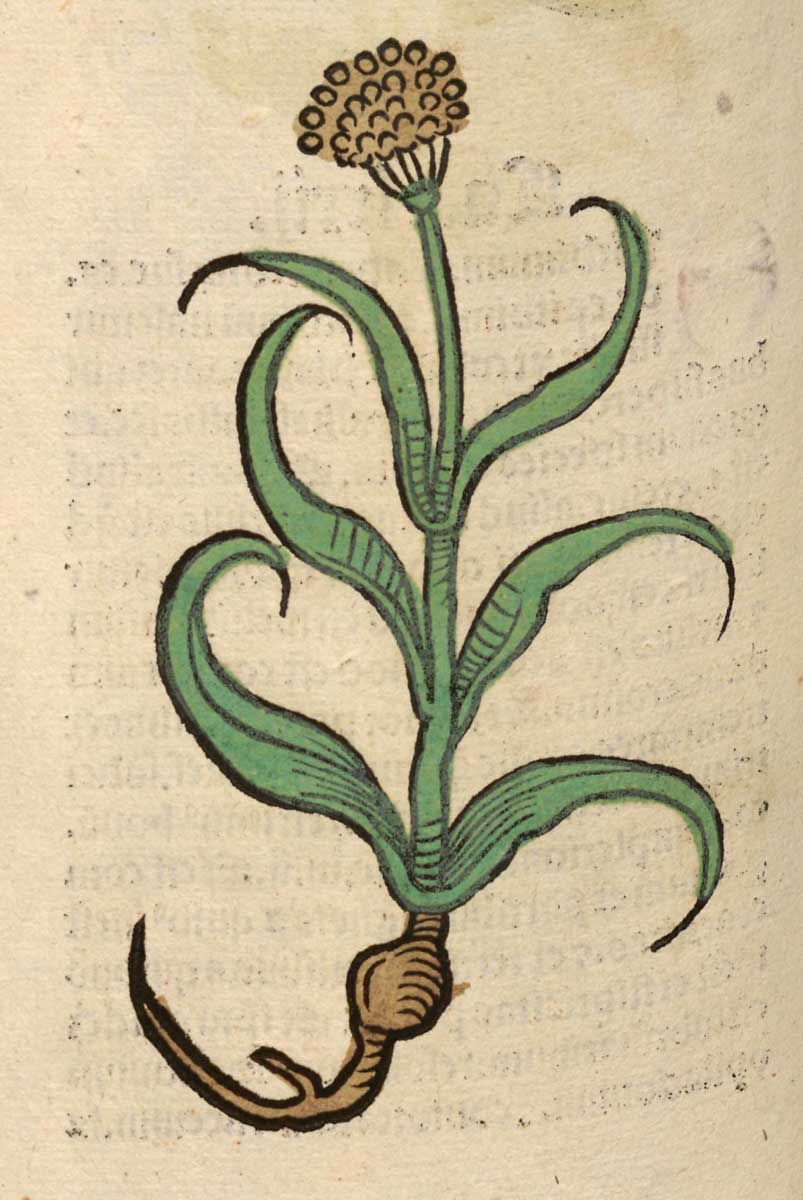

Effemereon

Effemereon (text)

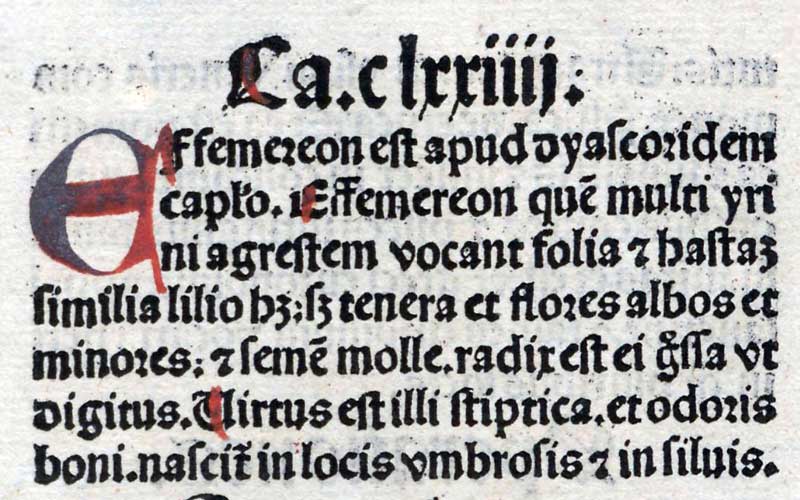

Crocus

Crocus (text)

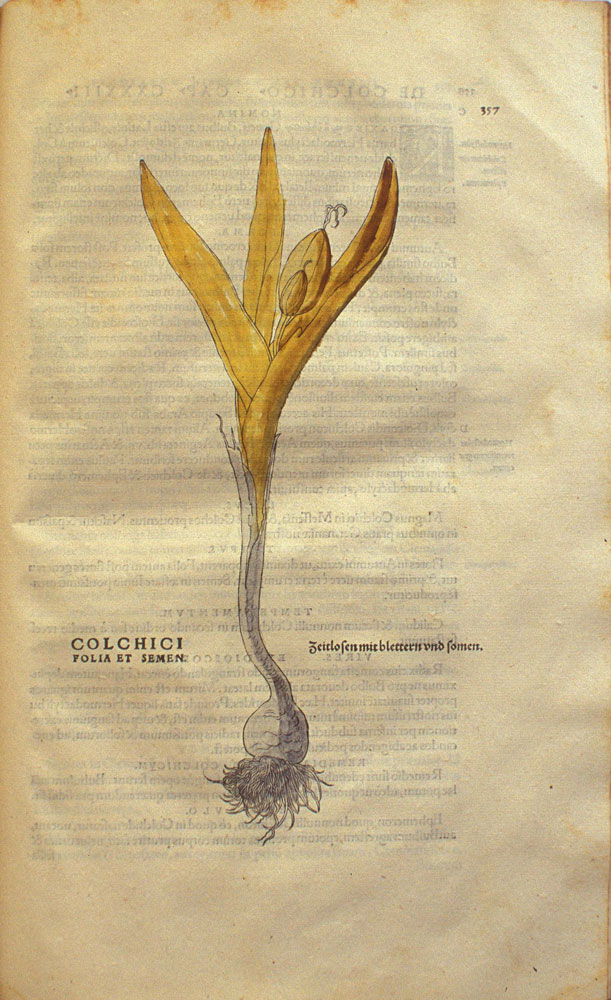

Colchici

Colchici

folia et semen

Zeitlosen mit blettern und somen

Taxon: Colchicum autumnale L.

English: meadow saffron

Ephemerum

Pliny xxv. 13, § 107.

Ephemerum

Ephemeron folia habet lilii, sed minora; caulem parem, florem caeruleum, semen supervacuum, radicem unam digitali crassitudine, dentibus praecipuam concisam in aceto decoctamque ut tepido colluantur. et ipsa etiam radix sistit, cavis exesi inprimitur. chelidoniae radix ex aceto trita continetur ore, erosis veratrum nigrum inprimitur, mobiles utrolibet decocto in aceto firmantur.

Ephemeron has the leaves of a lily, but smaller, a stem of the same length, a blue flower, a seed of no value, and a single root of the thickness of a thumb, a sovereign remedy for the teeth if it is cut up into pieces in vinegar, boiled down, and used warm as a mouth wash. And the root also by itself arrests decay if forced into the hollow of a decayed tooth. Root of chelidonia is crushed in vinegar and kept in the mouth, dark hellebore is plugged into decayed teeth, and loose teeth are strengthened by either of these boiled down in vinegar

ephemerum

Plante décrit par Pline, XXV, 107: « Ephemeron folia habet lilii, sed monora, caulem parem, florem cæruleum. » Cette description a donné lieu à une foule d’hypothéses: Fée pense à Convallaria verticillata, L. Il y a un autre ephemeron ainsi nommé parce que eodem die possit occidere, décrit par Théophraste (H. P. IX, 16), chantee par Nicandre:

Si quisquam infestos Medeæ Colchidis ignes

Incautus gustarit ephemeron, ille repente

Uritur…

(Nic. Alexipharmaca)

mentionné par Dioscoride (IX, 84), prescrit, au cinquième siècle, sous le nom d’hermodacte par le byzantin Jacques Psychriste, et qui est le colchique: « Colchicon, alii ephemeron, Romani bulbum agrestem, exitu autumni florem fundit croceo similem », dit Ruellius, De nat. stirp. libri tres, Paris, S. de colines, 1536, in-f°, l. III, ch. 115, p. 832. « Ephemerum, que quelquesuns nomment Colchicon ou bulbe sauvage. » Paré, l. XXI, des venins, ch. 43. C’est Colchicum autumnale, L. — Le colchicum minus de Pena et Lobel est C. arenarium, Wald. et Kit. Le colchique renferme un alcaloïde trés actif, la colchicine. (Paul Delaunay)

ephemerum

thus ephemerum, perhaps colchicum (meadow saffron, autumn crocus, which, used pharmaceutically, is narcotic, diuretic, cathartic and excellent for rheumatism)…

nommés pas leurs vertus et operations

Sauf pour le lichen, tous les détails sont dans De latinis nominibus («Alysson … dicitur (ut ait Galenus) quod mirifice morsus a cane rabido curet. [gk] enim rabiem significat. Ephemerium… quo die sumptum fuerit (ut nominis ipsa ratio ostendit) intermit. Bechion autem appellatum est, quod [gk], id es tusses … juvet. Nasturtium, cresson alenois … dicitur a torquendis naribus. Hyoscame, faba suis, vulgo hannebane, … dicitur … quot pastu ejus convellantur sues ». R. a mal lu ses notes, faisant de hanebanes une plante différente de l’hyoscame.

Callithricum, which makes the hair beautiful

Callithricum, which makes the hair beautiful.

Original French: Callithrichum, qui faict les cheueulx beaulx.

Modern French: Callithrichum, qui faict les cheveulx beaulx.

Among the plants named for their virtues and operations.

Notes

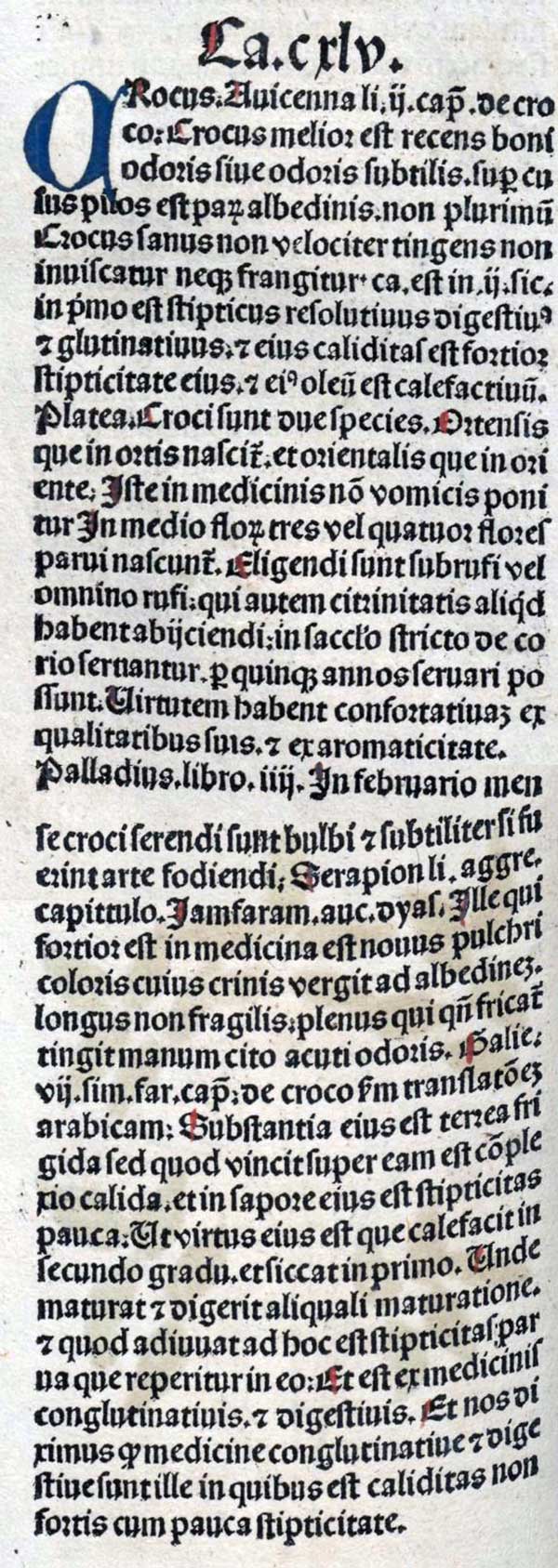

Saxifraga

Capillus Veneris

Lenticula

Capillus Veneris (text)

Adiantum

Taxon: Adiantum capillus-veneris L.

Ancient Greek:adianton

English: Venus’s-hair fern, Southern maidenhair

French: Capillaire cheveux-de-Vénus, Cheveux de Vénus, Capillaire, Chevelure de Vénus, Capillaire de …

German: Frauenhaar, Jungfernhaar, Venushaar

callitrichum

Iocineris doloribus . . . scorpio marinus in vino necatus, ut inde bibatur, conchae longae carnes ex mulso potae cum aquae pari modo aut, si febres sint, ex aqua mulsa. Lateris dolores leniunt hippocampi tosti sumpti tetheaque similis ostreo in cibo sumpta, ischiadicorum muria siluri clystere infusa. dantur autem conchae ternis obolis dilutis in vini sextariis duobus per dies xv.

For liver pains are good: … a sea scorpion drowned in wine, so that the liquor may be drunk, or the flesh of the long mussel taken in honey wine with an equal quantity of water, or if there is fever in hydromel. Pains in the side are relieved by eating the flesh of the sea-horse roasted, or the tethea, which resemblesa the oyster, taken in the food; sciatica is relieved by the brine of the silurus, injected as an enema. Mussels too are given for fifteen days in doses of three oboli soaked in two sextarii of wine.

callitrichum

Aliud adianto miraculum: aestate viret, bruma non marcescit, aquas respuit, perfusum mersumve sicco simile est—tanta dissociatio deprehenditur—unde et nomen a Graecis alioqui frutici topiario. quidam callitrichon vocant, alii polutrichon, utrumque ab effectu. tinguit enim capillum et ad hoc decoquitur in vino cum semine apii adiecto oleo copiose, ut crispum densumque faciat; et defluere autem prohibet. duo eius genera: candidius et nigrum breviusque. id quod maius est, polytrichon, aliqui trichomanes vocant. utrique ramuli nigro colore nitent, foliis felicis, ex quibus inferiora aspera ac fusca sunt, omnia autem contrariis pediculis densa ex adverso inter se, radix nulla. umbrosas petras parietumque aspergines ac fontium maxime cum aquas non sentiat. calculos e corpore mire pellit frangitque, utique nigrum, qua de causa potius quam quod in saxis nasceretur a nostris saxifragum appellatum crediderim. bibitur e vino quantum terni decerpsere digiti. urinam cient, serpentium et araneorum venenis resistunt, in vino decocti alvum sistunt. capitis dolores corona ex his sedat. contra scolopendrae morsus inlinuntur, crebro auferendi ne perurant, hoc et in alopeciis. strumas discutiunt furfuresque in facie et capitis manantia ulcera. decoctum ex his prodest suspiriosis et iocineri et lieni et felle subfusis et hydropicis. stranguriae inlinuntur et renibus cum absinthio. secundas cient et menstrua. sanguinem sistunt ex aceto aut rubi suco poti. infantes quoque exulcerati perunguntur ex iis cum rosaceo et vino prius. folium in urina pueri inpubis, tritum quidem cum aphronitro et inlitum ventri mulierum ne rugosus fiat praestare dicitur. perdices et gallinaceos pugnaciores fieri putant in cibum eorum additis, pecorique esse utilissimos.

Maidenhair too is remarkable, but in other ways. It is green in summer without fading in winter; it rejects water; sprinkled or dipped it is just like a dry plant—so great is the antipathy manifested—whence too comes the name given by the Greeks [bἀδίαντον, “water proof”] to what in other respects is a shrub for ornamental gardens. Some call it lovely hair [καλλίτριχον] or thick hair [πολύτριχον], both names being derived from its properties. For it dyes the hair, for which purpose a decoction is made in wine with celery seed added and plenty of oil, in order to make it grow curly and thick; moreover it prevents hair from falling out. There are two kinds: one is whiter than the other, which is dark and shorter. The larger kind, thick hair, is called by some trichomanes [Mad on hair, i.e. with wild hair (?)]. Both have sprigs of a shiny black, with leaves like those of fern, of which the lower are rough and tawny, but all grow from opposite footstalks, close set and facing each other; there is no root. It is mostly found on shaded rocks, walls wet with spray, especially the grottoes of fountains, and on boulders streaming with water—strange places for a plant that is unaffected by water! It is remarkably good for expelling stones from the bladder, breaking them up, the dark kind does so at any rate. This, I am inclined to believe, is the reason why it is called saxifrage (stone-breaker) [Stones in the bladder are calculi not saxa] rather than because it grows on stones. It is taken in wine, the dose being what can be plucked with three fingers. Diuretic, the maidenhairs [The change to the masculine plural is odd. Perhaps Pliny took callitrichon and polytrichon as masculines. The other alternative is to understand ramuli (see § 63), which Mayhoff thinks has fallen out here] counteract the venom of snakes and spiders; a decoction in wine checks looseness of the bowels; a chaplet made out of them relieves headache. An application of them is good for scolopendra stings, though it must be taken off repeatedly for fear of burns. The same treatment applies to fox-mange also. They disperse scrofulous sores, scurf on the face and running sores on the head. A decoction of them is beneficial for asthma, liver, spleen, violent biliousness and dropsy. With wormwood an application of them is used in strangury and to help the kidneys. They promote the afterbirth and menstruation. Taken in vinegar or blackberry juice they check haemorrhage. Sore places too on babies are treated by an ointment of maidenhair with rose oil, wine being applied first. The leaves steeped in the urine of a boy not yet adolescent, if they be pounded with saltpetre and applied to the abdomen of women, prevent the formation of wrinkles. It is thought that partridges and cockerels become better fighters if maidenhair be added to their food, and it is very good for cattle.

callitrichum

Fit et ex callitriche sternumentum. folia sunt lenticulae, caules iunci tenuissimi radice minima. nascitur opacis et umidis, gustatu fervens.

From callithrix also is made a snuff. This plant has the leaves of the lentil; the stems are very slender rushes and the root is very small. It grows in shady, moist places, and has a hot taste.

Callithrichum

Du grec χαλλίτριχοζ, pulchros pilos habens vel faciens.

Callitrichum

Pliny xxxii. 21, § 30.

callithrichum

Le callitrichos ou callithrix ou Adianton de Pline, XXII, 30, XXV, 86 est l’Asplenium trichomanes, L., ou doradille. Pline lui confère par erreur les propriétés de l’ὰσίαντον χαὶ πολύτριχον de Dioscoride (IV, 136), qui est notre capillaire de Montpellier, Adiantum capillus Veneris, L. C’est le pétiole des frondes de ce dernier, brun, luisant, lisse et mince, que l’on a voulu comparer à un cheveu (cheveux de Vénus) et employer, en vertu de la doctrine des analogies, contre la calvitie, ainsi que le préconise en 1644, avec enthousiasme, Pierre Formi, de Montpellier. Cf. H. Leclerc, Le Capillaire, Courrier médical, 72e année, n° 43, 26 novembre 1922, p. 505-506. (Paul Delaunay)

callithrica

thus callithrica — water starwort, or stargrass — whose leafstalk suggests hair, and which is a specific against baldness…

nommés pas leurs vertus et operations

Sauf pour le lichen, tous les détails sont dans De latinis nominibus («Alysson … dicitur (ut ait Galenus) quod mirifice morsus a cane rabido curet. [gk] enim rabiem significat. Ephemerium… quo die sumptum fuerit (ut nominis ipsa ratio ostendit) intermit. Bechion autem appellatum est, quod [gk], id es tusses … juvet. Nasturtium, cresson alenois … dicitur a torquendis naribus. Hyoscame, faba suis, vulgo hannebane, … dicitur … quot pastu ejus convellantur sues ». R. a mal lu ses notes, faisant de hanebanes une plante différente de l’hyoscame.

Callithrichum

Voir Pline, XX,xxx, et XXV, lxxvi.

Lichen which cures the maladies of its name

Lichen which cures the maladies of its name.

Original French: Lichen qui gueriſt les maladies de ſon nom.

Modern French: Lichen qui guerist les maladies de son nom.

Among the plants named for their virtues and operations.

Notes

lichen

Les dartres.

Lichen

Les dartres: lichen signifie en effet dartre vive, en latin.

Lichen

Pliny xxvi. 4, § 10.

lichen

Sed in lichenis remediis atque tam foedo malo plura undique acervabimus quamquam non paucis iam demonstratis. medetur ergo plantago trita, quinquefolium, radix albuci ex aceto, ficulni caules aceto decocti, hibisci radix cum glutino et aceto acri decocta ad quartas. defricant etiam pumice, ut rumicis radix trita ex aceto inlinatur et flos visci cum calce subactus. laudatur et tithymalli cum resina decoctum, lichen vero herba omnibus his praefertur, inde nomine invento. nascitur in saxis, folio uno ad radicem lato, caule uno parvo, longis foliis dependentibus. haec delet et stigmata, teritur cum melle. est aliud genus lichenis, petris totum adhaerens ut muscus, qui et ipse inlinitur. hic et sanguinem sistit volneribus instillatus et collectiones inlitus. morbum quoque regium cum melle sanat ore inlito et lingua. qui ita curentur aqua salsa lavari iubentur, ungui oleo amygdalino, hortensiis abstinere. ad lichenas et thapsiae radice utuntur trita cum melle.

But of lichen, which is so disfiguring a disease, I shall amass from all sources a greater number of remedies, although not a few have been noticed already. Remedies, then, are pounded plaintain, cinquefoil, root of asphodel in vinegar, shoots of the fig-tree boiled down in vinegar, and the root of hibiscus with bee-glue and strong vinegar boiled down to one quarter. The affected part is also rubbed with pumice, as a preparation for the application of rumex root pounded in vinegar, or of mistletoe scum [The glue-like juice of the mistletoe found chiefly in the berry. For this sense of flos cf. Virgil, Georgics, IV. 39: fucoque et floribus oras | explent, collectumque haec ipsa ad munera gluten | et visco et Phrygiae servant pice lentius Idae.] kneaded with lime. A decoction too of tithymallus with resin is highly recommended; the plant lichen however is considered a better remedy than all these, a fact which has given the plant its name. It grows among rocks, has one broad leaf near the root, and one small stem with long leaves hanging down from it. This plant removes also marks of scars; it is pounded with honey. There is another kind of lichen, entirely clinging, as does moss, to rocks; this too is used by itself as a local application. It also stops bleeding if the juice is dropped into wounds, and applied locally it is good for gatherings. With honey also it cures jaundice, if the mouth and tongue are smeared with it. Patients undergoing this treatment are ordered to bathe in salt water, to be rubbed with almond oil, and to abstain from garden vegetables. To treat lichen is also used the root of thapsia pounded with honey.

lichen

Le mot lichen (λειχὴν), déjà employé par Hippocrate, désigne des affections cutanées ou dartres de nature fort diverse, et différentes du groupe de dermatoses auquel les nosographes modernes ont réservé le nom de lichen. Des textes de Dioscoride, Pline et Galien, il ressort que ce vocable fut transféré de la pathologie à la botanique, et après avoir désignee les dartres, s’appliqua à des cryptogames, à thalle circiné, farineux ou crustacé, simulant l’aspect des lésions cutanées. De plus, de par la théorie des analogies, ceux-là guérirent celles-ci. « In iis [prunis sylvestribus] et sativis prunis est limuis arborum uem Græci lichena appellant, rhagadiis et condylomatis vere utilis », dit Pline, XXIII, 69. Ce lichen du prunellier pourrait ètre Evernia prunastri, Auch. Par contre, les 2 var. de lichen que Pline mentionne ailleurs, XXVI, 10, ne semblent point se rapporter à des lichens, mais plutôt a des Hépatiques : Marchantia polymorpha, L., et M. stellata, Scop. (Paul Delaunay)

lichen

Et in his et sativis prunis est limus arborum quem Graeci lichena appellant, rhagadis et condylomatis mire utilis.

Both on wild and on cultivated plum trees there forms a gummy substance called lichen by the Greeks and wonderfully beneficial for chaps and condylomata.

lichen

thus lichen, a plant botanically blotchy and, medicinally, a cure for skin diseases…

Lichen

Nom qui désigne d’abord des dermatoses caractétisées par des papules.

nommeés par leurs vertus

Le livre d’Estienne fournit toutes ces informations, lichen excepté. Rabelais se souvient sans doubt, sur ce dernier point, d’un auteur qu’il a partiellement édité: Manardi, Epistolae medicinales, XVIII, 3. — Hyoscyame («fève de pourceau») et hanebanes sont même chose, mais les deux noms n’ont pas le même sens. Le second fera encore écrire à Nicot: «Hanebane […] est poison aux poules, de sorte que si le grain qui leur est donné en est frotté, elles meurent. L’Anglois dit Henbene, qui signifie Poison aux Gelines, ou Mort à Gelines.»