the seed of fern, to pregnant women;

Original French: la graine de Fougere, aux femmes enceintes:

Modern French: la graine de Fougère, aux femmes enceintes:

Among the examples of pairings whose antipathies are not as vehement as the hatred thieves have of a certain usage of Pantagruelion.

Notes

la graine de Fougere, aux femmes enceintes

«Si [filix fœmina] mulieribus gravidis detur, abortum facere, si ceteris, steriles in totum reddere aiunt» (Théophraste, H.P., IX, 20, according to Delaunay.)

“If [fern female] given to pregnant women, performing an abortion if the other, they are the barren, they say that on the whole to render ” (Google translate)

I can’t find this reference in Theophrastus.

fougere

Filicis duo genera. nec florem habent nec semen. pterim vocant Graeci, alii blachnon, cuius ex una radice conplures exeunt filices bina etiam cubita excedentes longitudine, non graves odore. hanc marem existimant. alterum genus thelypterim Graeci vocant, alii nymphaeam pterim, est autem singularis atque non fruticosa, brevior molliorque et densior, foliis ad radicem canaliculata. utriusque radice sues pinguescunt, folia utriusque lateribus pinnata, unde nomen Graeci inposuere. radices utriusque longae in oblicum, nigrae, praecipue cum inaruere. siccari autem eas sole oportet. nascuntur ubique, sed maxime frigido solo. effodi debent vergiliis occidentibus. usus radicis in trimatu tantum, neque ante nec postea. pellunt interaneorum animalia, ex his taenias cum melle, cetera ex vino dulci triduo potae, utraque stomacho inutilissima. alvum solvit primo bilem trahens, mox aquam, melius taenias cum scamonii pari pondere. radix eius pondere duum obolorum ex aqua post unius diei abstinentiam bibitur, melle praegustato, contra rheumatismos. neutra danda mulieribus, quoniam gravidis abortum, ceteris sterilitatem facit. farina earum ulceribus taetris inspergitur, iumentorum quoque in cervicibus. folia cimicem necant, serpentem non recipiunt, ideo substerni utile est in locis suspectis, Usta etiam fugant nidore. fecere medici huius quoque herbae discrimen, optima Macedonica est, secunda Cassiopica.

Ferns are of two kinds, neither having blossom or seed. Some Greeks call pteris, others blachnon, the kind from the sole root of which shoot out several other ferns exceeding even two cubits in length, with a not unpleasant smell. This is considered male. The other kind the Greeks call thelypteris, some nymphaea pteris. It has only one stem, and is not bushy, but shorter, softer and more compact than the other, and channelled with leaves at the root. The root of both kinds fattens pigs. In both kinds the leaves are pinnate on either side, whence the Greeks have named them “pteris” [The Greek πτερόν means “feather”]. The roots of both are long, slanting, and blackish, especially when they have lost moisture; they should, however, be dried in the sun. Ferns grow everywhere, but especially in a cold soil. They ought to be dug up at the setting of the Pleiades. The root must be used only at the end of three years, neither earlier nor later. Ferns expel intestinal worms, tapeworms when taken with honey, but for other worms they must be taken in sweet wine on three consecutive days; both kinds are very injurious to the stomach. Fern opens the bowels, bringing away first bile, then fluid, tapeworms better with an equal weight of scammony. To treat catarrhal fluxes two oboli by weight of the root are taken in water after fasting for one day, with a taste of honey beforehand. Neither fern should be given to women, since either causes a miscarriage when they are pregnant, and barrenness when they are not. Reduced to powder they are sprinkled over foul ulcers as well as on the necks of draught animals. The leaves kill lice and will not harbour snakes, so that it is well to spread them in suspected places; by the smell too when burnt they drive away these creatures. Among ferns also physicians have their preference; the Macedonian is the best, the next best comes from Cassiope [A town in Corcyra].

Fern-seed to Women with Child

Pliny xxvii. 9, § 55 (80).

la graine de Fougere, aux femmes enceintes

«Si [filix fœmina] mulieribus gravidis detur, abortum facere, si ceteris, steriles in totum reddere aiunt» (Théophraste, H.P., IX, 20). «Neutra [filix] danda mulieribus, quoniam gravidis abortum, cæteris sterilitatem facit» (Pline, XXVII, 55). — Le πτερὶζ de Dioscoride et Théophraste, blechnon ou Fougére mâle de Pline, est pour Fée notre Polypodium [Polystichum] filix mas, L. Le Θηλνπτερίζ de Théophraste et Dioscoride, Nymphæa pteris ou filix femina de Pline est pour Fée notre Polypodium [asplenium] filix femina, L. La fougère mâle passait jadis pour abortive. On ne lui reconnaît plus que des vertus tænifuges, encore que les propriétés toxiques de la filicine en rendent l’emploi peu recommendable pour la femme enciente. (Paul Delaunay.)

Nenuphar…

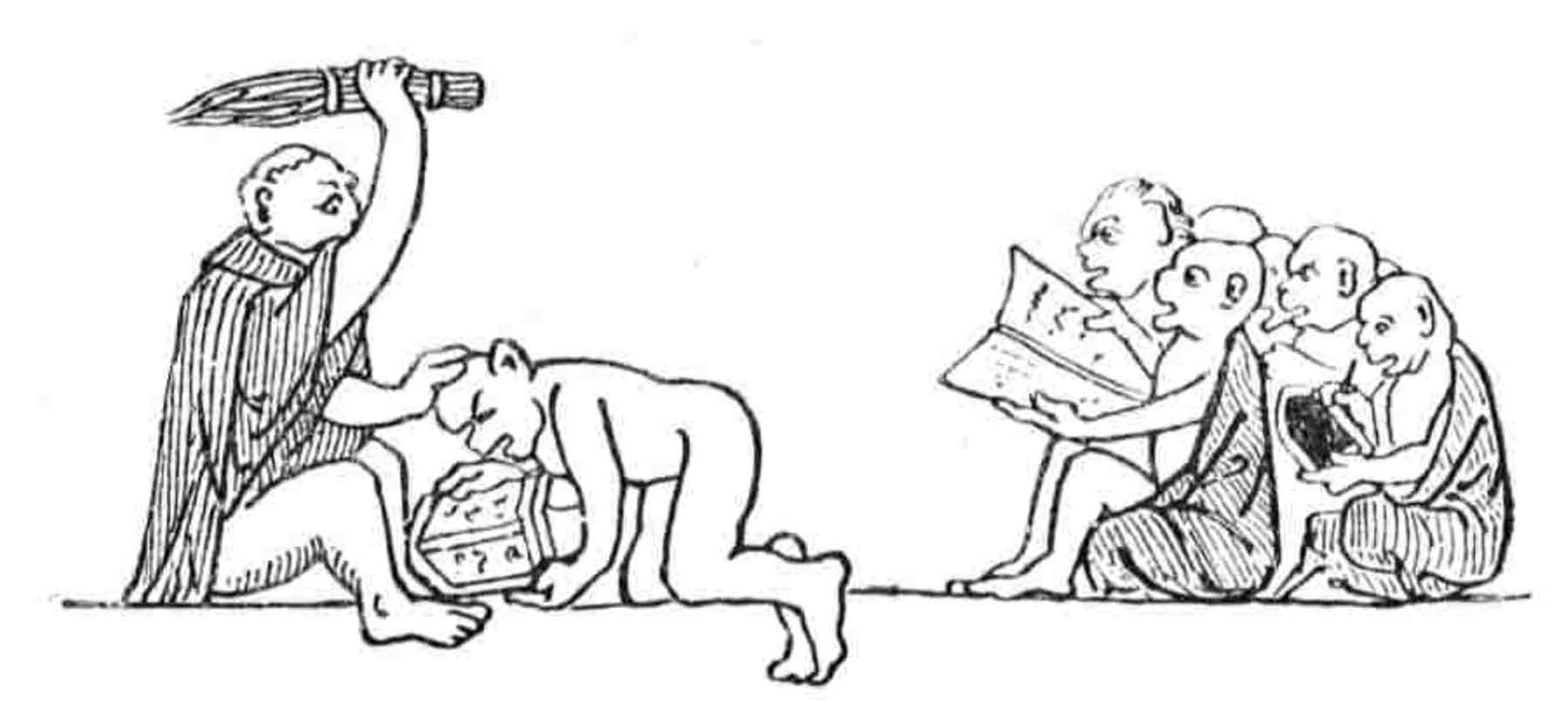

Encore une fois, la plupart de ces exemples se retrouvent dans le De latinis nominibus de Charles Estienne. Le nenufar et la semence de saule sont des antiaphrodisiaques. La ferula servait, dans l’Antiquité, à fustiger les écoliers (cf. Martial, X, 62-10).

la graine de Fougère, aux femmes enceintes

Considérée comme abortive.