Among the examples of pairings whose antipathies are not as vehement as the hatred thieves have of a certain usage of Pantagruelion.

The section from “La presle aux fauscheurs” (horse-tail to mowers) to “le Lierre aux Murailles” (ivy to walls), including this phrase, was added in the 1552 edition.

Notes

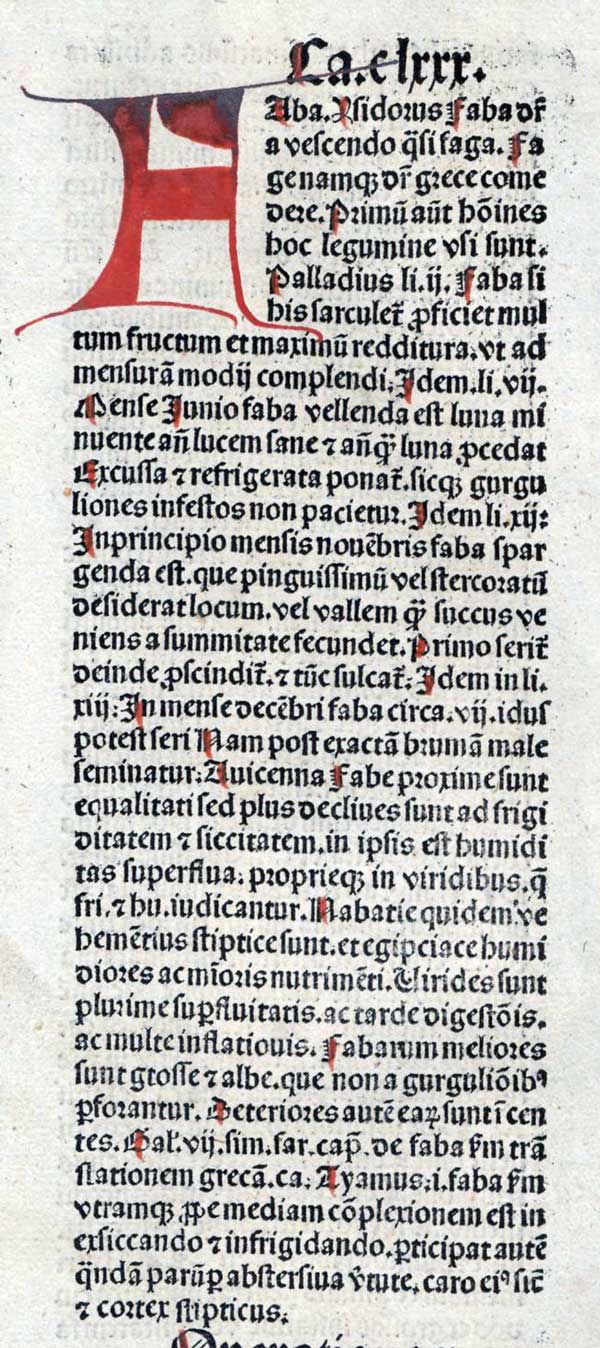

Faba

Faba

Wind at Philippi

The tree gets scorched by this wind right down to the trunk, and in general the upper are caught more and earlier than the lower parts. The effects are seen partly at the actual time of budding, but in the olive, because it is evergreen, they do not appear till later; those trees therefore which have shed their leaves come to life again, but those that have not done so are completely destroyed. In some places trees have been known, after being thus scorched and after their leaves have withered, to shoot again without shedding their leaves, and the leaves have come to life again. Indeed in some places, as at Philippi, this happens several times.

The beans at Philippi

In the district of Philippic, if the beans, while being winnowed, are caught by the prevailing wind of the country, they become ‘uncookable,’ having previously been ‘cookable.’

The beans at Philippi

But that what makes the seeds stubborn is a stiffening and closing of texture brought about by cold is attested by what occurs to the beans at Philippi. A very cold wind rises there and blows on the beans during the winnowing too. If it blows on them as they lie threshed on the threshing floor among the chaff and stripped of the pod, they do not change but remain ready, for they are sheltered partly by the chaff and partly by their contact with one another, and then too by the warmth of the ground. Whereas if the wind catches them off the ground, the wind has greater strength and enters and stiffens them when they have no shelter on any side; and at the same time the seeds then reach their weakest state, since they are now for the first time divested of the chaff and of the warmth that had hitherto enveloped them, and it is the great changes that have the greatest effect.1

1. One may suspect that the labourers preferred to await a warmer wind for the task of winnowing and devised this excuse for the delay.

ateramon

circa Philippos ateramum nominant in pingui solo herbam qua faba necatur, teramum qua in macro, cum udam quidam ventus adflavit.

In the neighbourhood of Philippi [This comes from Theophrastus De causis IV. 14 who only says that at Philippi a cold wind makes the bean ἀτεράμων hard and difficult to cook. From this adjective Pliny coins two proper names.] they give the name of ateramum to a weed growing in rich soil that kills the bean plant, and the name teramum to one that has the same effect in thin soil, when a particular wind has been blowing on the beans when damp.

Antranium (ateramon) to Beans

Pliny xviii. 17, § 44 (155)

antranium aux febves

Antranium, graphie vicieuse qui n’existe que dans l’ed. incunable de Pline, Venise, 1469, et que Rabelais a copiée sans plus ample informé. Les éd. ou traductions postérieures portent ateranum (Paris, 1516), ateramnos, ateramos (du Pinet, 1562) ateramon, ateramum, teramum, teramnon, teramon. Dans Théophraste (H.P., VIII, 9), ἀτεράμων signifie dur cru, difficile à cuire, et τεράμων tendre. Ailleurs (De causis plant., IV, 14) Théophraste parle des fèves qui poussent aux environs de Phillipes et que les vents froids durcissent. Pline a copié ce passage à la légère prenant ces adjectifs pour le nom de plantes nuisibles aux fèves: «Circa Philippos antranium nominant in pingui solo herbam qua faba necatur; teramim quum in macro, cum udam quidam ventus adflavit» (XVIII, 44). «Aux environs de la ville de Philippes, il en est une [plante] qui fait périr la fève; on l’appelle ateramon quand elle croît dans un terrain gras, et teramon quand elle vient dans un terrain maigre, et tue la fève qui a reçu l’impression du vent étant mouillée». Et Duchesne tomba dans le même contresens: «atermon, herba fabas enecans». (Paul Delaunay)

orobanche, aegilops, securidaca, antranium, l’yvraye

Les cinq exemples suivants sont tous empruntés au même chapitre de Pline (XVIII, 44) (LD).

antranium

Graphie fautive pour ateranum, présente dans l’édition de Pline, Venuse, 1469; voir Tiers livre, éd .Lefranc, n. 8, p. 359.