Among the plants that do not attire so many people as does Pantagruelion.

Notes

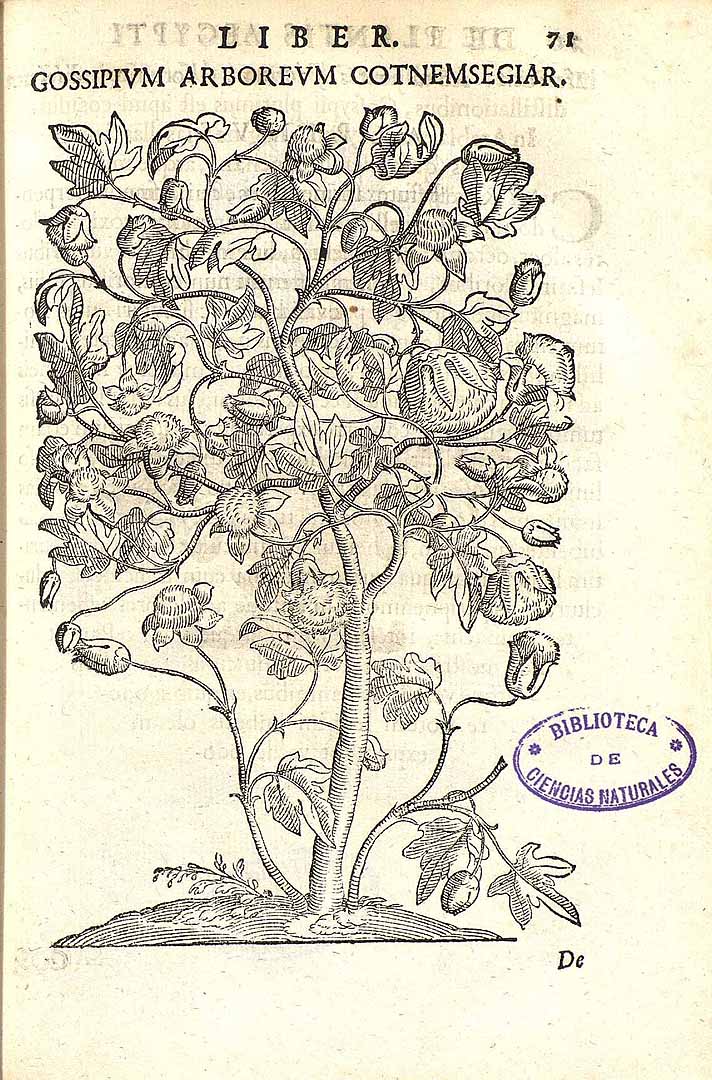

Gossipium arboreum

De plantis Aegypti liber, editio altera emendatior

71

Venice, 1592 (reprint 1640)

Plant Illustrations

Swans of the Arabs

Web

Cynes

Arbre d’Arabie, que Pline appelle Cyna.

Le Rabelais moderne, ou les Œuvres de Rabelais mises à la portée de la plupart des lecteurs

p. 160

François-Marie de Marsy [1714-1763], editor

Amsterdam: J.-F. Bernard, 1752

Google Books

les Cynes des Arabes

On lit au même endroit de Pline (liv. XII, chap. XI); Juba tradit … Arabiœ arbores ex quibus vestes faciant, cynus vocari, folio palmœ simili. Mais quel est cet arbre, dont le nom vient de χυων, χυνὀζ, chien? Seroit-ce le même que l’églantier ou rosier sauvage que les Grecs nommient χυνἀζ et les Romains rubus caninus, lequel est nommé cynus, et traduit par aubépine dans le supplément au glossaire de Ducange? La forme des feuilles s’y oppose, ce nous semble: χυνἀζ et cynus viennent cependant également de χύων. Ce qui nous fait penser que le mot grec χίννα, genus graminis in Ciliciâ, pourroit bien en venir aussi, puisque c’étoit le nom d’une espèce de chiendent. Nous laissons aux botanistes de profession ces questions à résoudre.

Œuvres de Rabelais (Edition Variorum). Tome Cinquième

p. 281

Charles Esmangart [1736–1793], editor

Paris: Chez Dalibon, 1823

Google Books

cynes

Arbre qui servoit a fabriquer des étoffes.

Œuvres de F. Rabelais. Nouvelle edition augmentée de plusieurs extraits des chroniques admirables du puissant roi Gargantua… et accompagnée de notes explicatives…

p. 310

L. Jacob (pseud. of Paul Lacroix) [1806–1884], editor

Paris: Charpentier, 1840

le cynes des Arabes

«[Juba tradit]… Arabiæ… arbores ex quibus vestes faciant, cynas vocari, folio palmæ simili». (Pline, XII, 22.) C’est un cotonnier, et, d’après Fée, le Gossypium herbaceum L., form cultivée du G. Stocksii, d’après Masters. (Paul Delaunay)

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre

p. 366

Abel Lefranc [1863-1952], editor

Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931

Archive.org

les Cynes des Arabes

XXII. arborem vocant gossypinum, fertiliore etiam Tyro minore, quae distat x͞ p. Iuba circa fruticem lanugines esse tradit, linteaque ea Indicis praestantiora, Arabiae autem arborem ex qua vestes faciant cynas vocari, folio palmae simili. sic Indos suae arbores vestiunt. in Tyris autem et alia arbor floret albae violae specie, sed magnitudine quadruplici, sine odore, quod miremur in eo tractu.

XXII. Their name for this tree is the gossypinus; it also grows in greater abundance on the smaller island of Tyros, which is ten miles distant from the other. Juba says that this shrub has a woolly down growing round it, the fabric made from which is superior to the linen of India. He also says that there is an Arabian tree called the cynas [Perhaps Bombas ceiba] from which cloth is made, which has foliage resembling a palm-leaf. Similarly the natives of India are provided with clothes by their own trees. But in the Tyros islands there is also another tree [Tamarind] with a blossom like a white violet but four times as large; it has no scent, which may well surprise us in that region of the world.

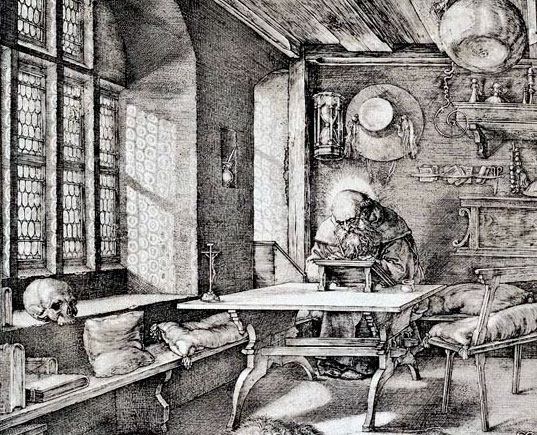

The Natural History. Volume 4: Books 12–16

12.22

Harris Rackham [1868–1944], translator

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1945

Loeb Classical Library

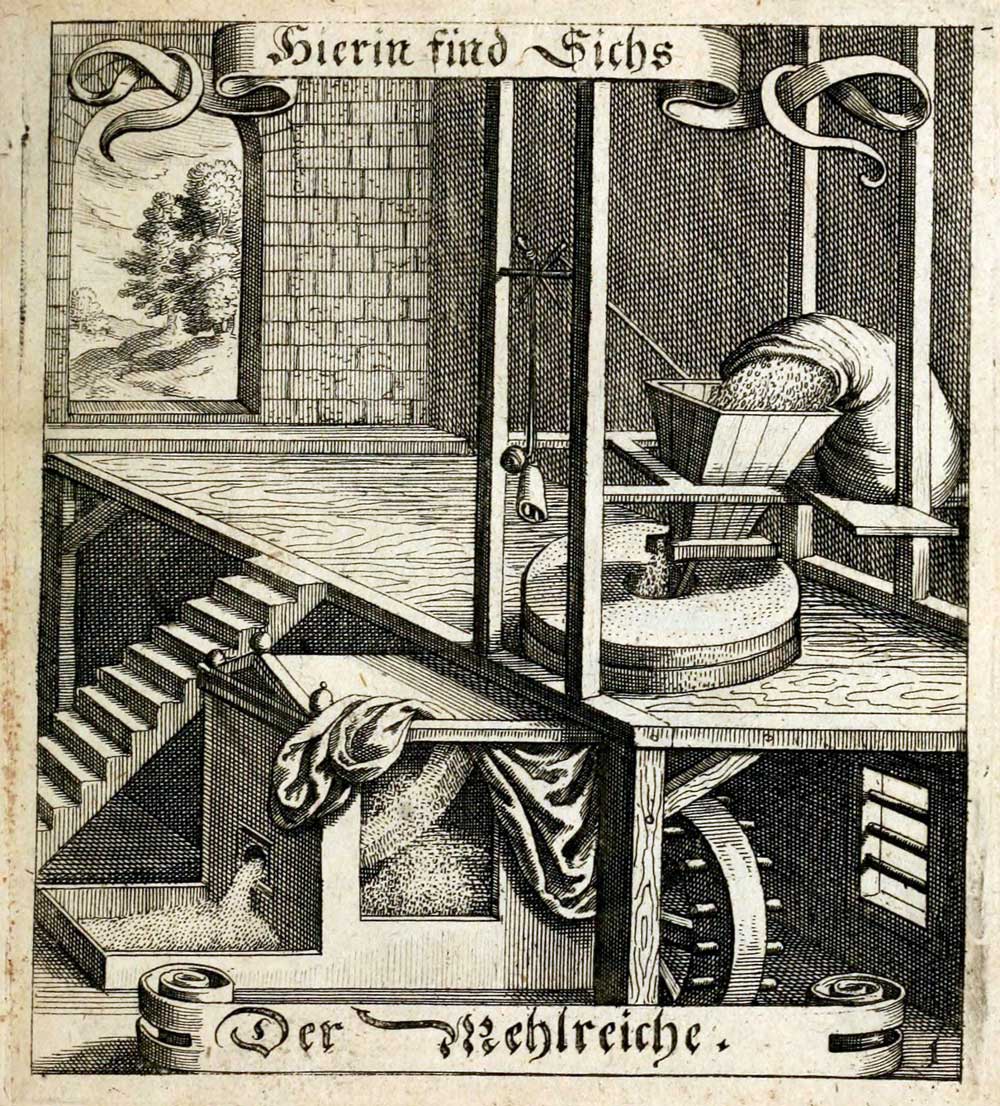

arbres lanificques, gossampines, cynes, les vignes de Malthe

Il s’agit de la soie et du coton (Pline, XII, 21 et 22). Les gossampines (gossypion) sont assimilées au lin par Pline, XIX, 2. Le coton de Malthe était très réputé dans l’Antiquité, d’où la « Linigera Melite » de Scyllius, cité par Textor, Officina, lxxvi v. Cf Polydore Vergile, De Inventoribus rerum, III,vi ; Servius, Comment. in Georg., II, 121 (voir plus bas, LII, 146, note).

Le Tiers Livre. Edition critique

Michael A. Screech [b. 1926], editor

Paris-Genève: Librarie Droz, 1964