Notes

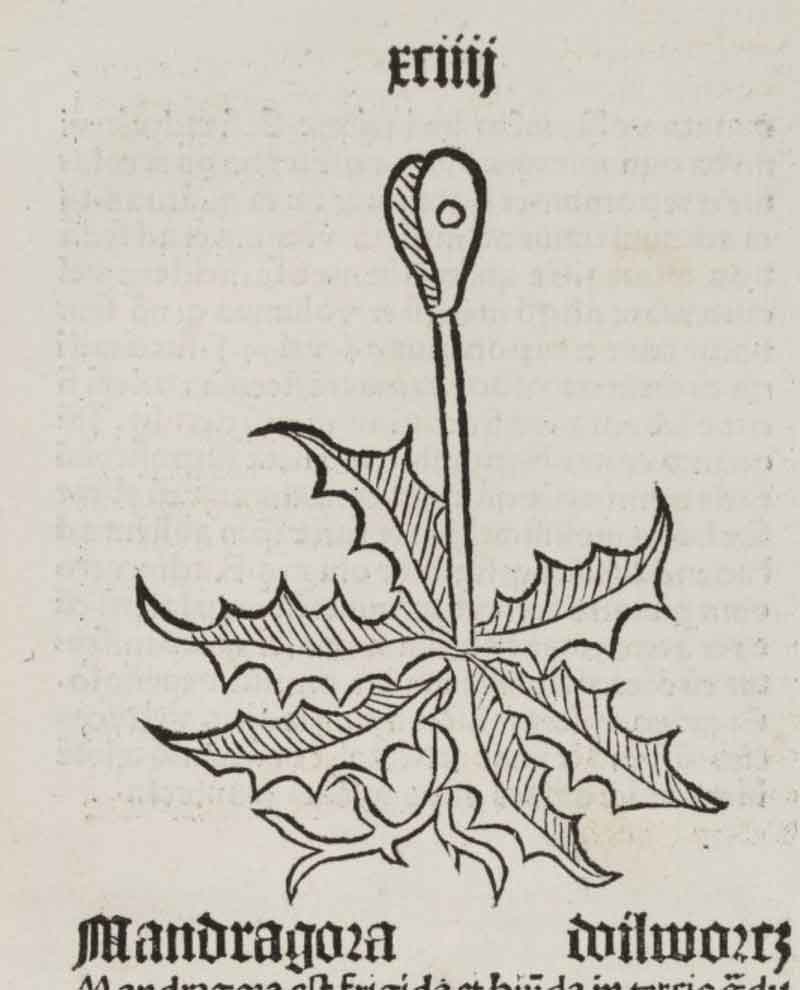

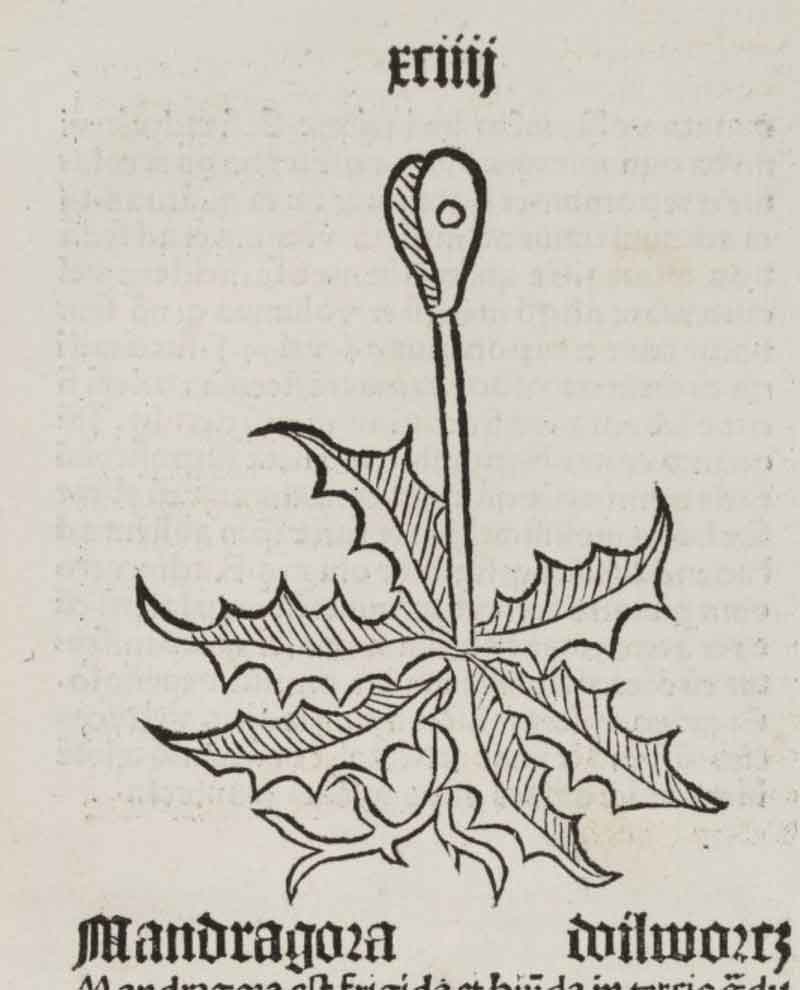

Mandragora

Schöffer, Peter (ca. 1425–ca. 1502),

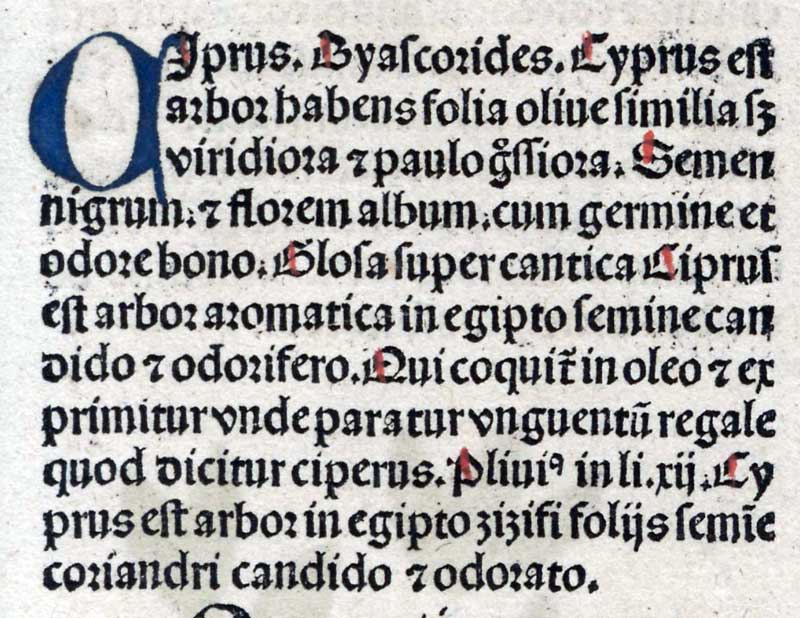

[R]ogatu plurimo[rum] inopu[m] num[m]o[rum] egentiu[m] appotecas refuta[n]tiu[m] occasione illa, q[uia] necessaria ibide[m] ad corp[us] egru[m] specta[n]tia su[n]t cara simplicia et composita. Mainz: 1484.

Botanicus

Mandragora

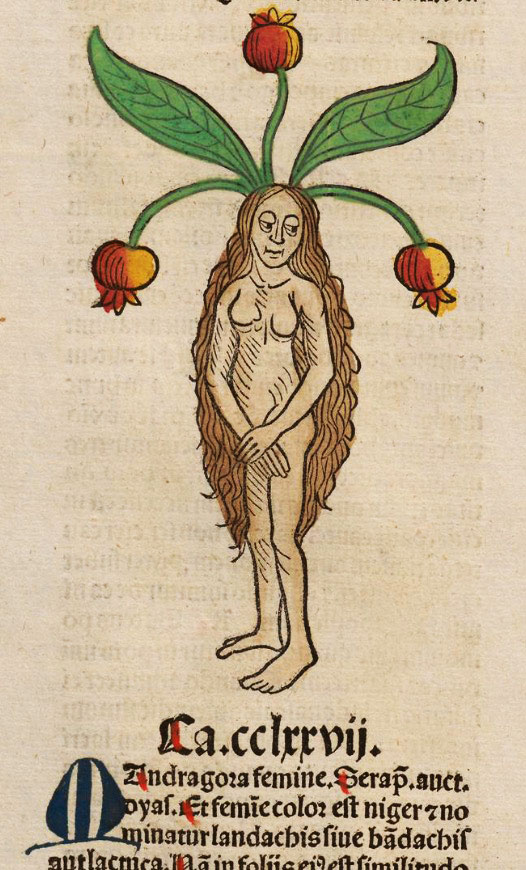

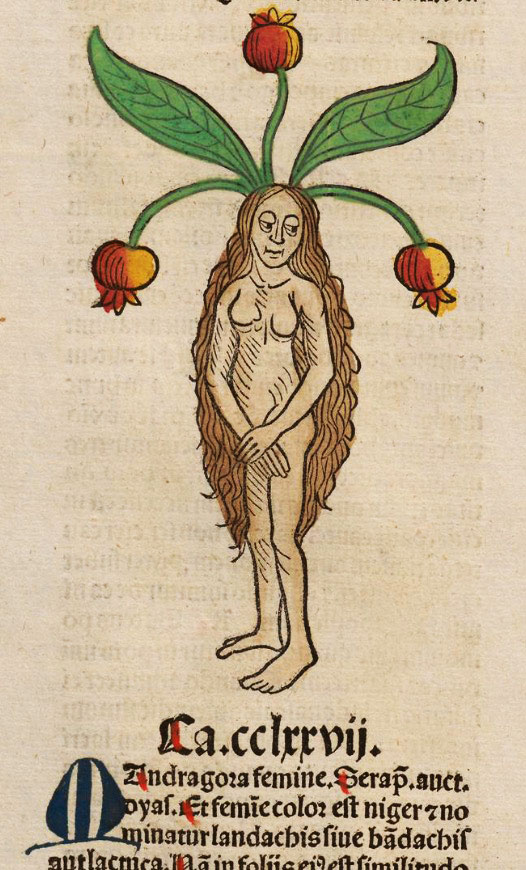

Mandragora femine

Mandragore

Mandragores mâle et femelle (Greek ΜΑΝΔΡΑΓΟΡΑ). Folio 90 from the Naples Dioscurides, a 7th century manuscript of Dioscurides’ De Materia Medica (Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale, Cod. Gr. 1).

mandragore

Aliqui et mandragora utebantur; postea abdicatus est in hac curatione. epiphoris, quod certum est, medetur et oculorum dolori radix tusa cum rosaceo et vino. nam sucus multis oculorum medicamentis miscetur. mandragoran alii circaeon vocant. duo eius genera; candidus qui et mas, niger qui femina existimatur, angustioribus quam lactucae foliis, hirsutis et caulibus, radicibus binis ternisve rufulis, intus albis, carnosis tenerisque, paene cubitalibus. ferunt mala abellanarum nucum magnitudine et in his semen ceu pirorum. hoc albo alii arsena, alii morion, alii hippophlomon vocant. huius folia alba, alterius latiora ut lapathi sativae. effossuri cavent contrarium ventum et tribus circulis ante gladio circumscribunt, postea fodiunt ad occasum spectantes. sucus fit et e malis et caule deciso cacumine et e radice punctis aperta aut decocta. utilis haec vel surculo. concisa quoque in orbiculos servatur in vino. sucus non ubique invenitur sed, ubi potest, circa vindemias quaeritur. odor gravis ei, set radicis et mali gravior ex albo. mala matura in umbra siccantur. sucus ex his sole densatur, item radicis tusae vel in vino nigro ad tertias decoctae. folia servantur in muria, efficacius albi. rore tactorum sucus pestis est. sic quoque noxiae vires. gravedinem adferunt etiam olfactu, quamquam mala in aliquis terris manduntur, nimio tamen odore obmutescunt ignari, potu quidem largiore etiam moriuntur. vis somnifica pro viribus bibentium. media potio cyathi unius. bibitur et contra serpentes et ante sectiones punctionesque, ne sentiantur. ob haec satis est aliquis somnum odore quaesisse. bibitur et pro helleboro duobus obolis in mulso—efficacius helleborum—ad vomitiones et ad bilem nigram extrahendam.

Some physicians used to employ theMandrake for the eyes, etc. mandrake also; afterwards it was discarded as a medicine for the eyes. What is certain is that the pounded root, with rose oil and wine, cures fluxes and pain in the eyes. But the juice is used as an ingredient in many eye remedies. Some give the name circaeon to the mandrake. There are two kinds of it: the white, which is also considered male, and the black, considered female. The leaves are narrower than those of lettuce, the stems hairy, and the roots, two or three in number, reddish [he nigris foris, “black outside,” of Hermolaus Barbarus, was suggested by Dioscorides IV. 75, μέλαιναι κατὰ τὴν ἐπιφάνειαν, ἔνδοθεν δὲ λευκαί. But even if foris can represent τὴν ἐπιφάνειαν, nigris foris was most unlikely to be corrupted to rufulis. The word μέλας often means “of the colour of port wine,” and rufulus is not very far away from that], white inside, fleshy and tender, and almost a cubit in length. They bear fruit of the size of filberts, and in these are seeds like the pips of pears. When the seed is white the plant is called by some arsen [“Male,” Greek ἄρσην. Fée thinks that the morion was not the mandrake but Atropa belladonna], by others morion, and by others hippophlomos. The leaves of this mandrake are whitish, broader than those of the other, and like those of cultivated lapathum. The diggers avoid facing the wind, first trace round the plant three circles with a sword, and then do their digging while facing the west. The juice can also be obtained from the fruit, from the stem, after cutting off the top, and from the root, which is opened by pricks or boiled down to a decoction. Even the shoot of its root can be used, and the root is also cut into round slices and kept in wine. The juice is not found everywhere, but where it can be found it is looked [Dioscorides, IV. 75 (Wellmann) has: ἔστι δὲ ἐνεργέστερος τοῦ ὀποῦ ὁ χυλός. οὐκ ἐν παντὶ δὲ τόπῳ φέρουσιν ὀπὸν αἱ ῥίζαι ὑποδείκνυσι δὲ τὸ τοιοῦτον ἡ πεῖρα. Our two authorities differ here; there seems nothing in Pliny to correspond to ἡ πεῖρα] for about vintage time. It has a strong smell, but stronger when the juice comes from the root or fruit of the white mandrake. The ripe fruit is dried in the shade. The fruit juice is thickened in the sun, and so is that of the root, which is crushed or boiled down to one third in dark wine. The leaves are kept in brine, more effectively those of the white kind. The juice of leaves that have been touched by dew are deadly. Even when kept in brine they retain harmful properties. The mere smell brings heaviness of the head and—although in certain countries the fruit is eaten—those who in ignorance smell too much are struck dumb, while too copious a draught even brings death. When the mandrake is used as a sleeping draught the quantity administered should be proportioned to the strength of the patient a moderate dose being one cyathus. It is also taken in drink for snake bite, and before surgical operations and punctures to produce anaesthesia. For this purpose some find it enough to put themselves to sleep by the smell. A dose of two oboli of mandrake is also taken in honey wine instead of hellebore—but hellebore is more efficacious—as an emetic and to purge away black bile.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 7: Books 24–27. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1956. 25.094.

Loeb Classical Library

mandragore

Hermaphrodite, comme les autres Solanées. Les vieux auteurs prétendaient retrouver dans la bizzare conformation de la racine ne sorte d’ébauche humaine, tantôt mâle, tantôt femelle. (Cf. H. Leclerc, La mandragore, Presse médicale, no. 102, 23 décembre 1922, p. 2138-2140, et J. Avalon, La mandragore, son histoire, sa légend, Æsculape, 13e année, nos. 10 et 12, octobre et décember 1923, p. 223-337, 271-275). Pline décrit 2 esp. de Mandragore : « Candidus qui est mas, niger qui femina existimatur. » (XXV, 94). La mandragore femelle de Pline est pour Fée Mandragora autumnalis Bert., la mâle, M. vernalis Bert. Linnée n’en fait qu’une espèce, M. officinarum L. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 343.

Internet Archive

mandrake

mandrake. Forms: mandragge, mandrage, mandrag, mendrage, mandrake, mondrake, mandrak [Middle English mandrag(g)e, a shortening of mandragora; the form mandrake (mondrake), though recorded earlier than -drage, is prob. due to association with drake.]

Any plant of the genus Mandragora, native to Southern Europe and the East, and characterized by very short stems, thick, fleshy, often forked, roots, and fetid lance-shaped leaves. The mandrake is poisonous, having emetic and narcotic properties, and was formerly used medicinally. The forked root is thought to resemble the human form, and was fabled to utter a deadly shriek when plucked up from the ground. The notion indicated in the narrative of Genesis xxx, that the fruit when eaten by women promotes conception, is said still to survive in Palestine.

1382 John Wyclif Genesis xxx. 14 Ruben goon out in tyme of wheet heruest into the feeld, fonde mandraggis

[1388 mandragis].

C. 1440 Promptorium parvulorium sive cleriucorum 324/2 Mandragge, herbe,..mandragora.

1562 Leigh Armorie (1597) 99 b, He beareth Argent, a mandrage proper.

1580 Lyly Euphues (Arb.) 473 They that feare theyr Vines will make too sharpe wine, must..graft next to them Mandrage

[ed. 1581 Mendrage], which causeth the grape to be more pleasaunt.

1594 Lyly Moth. Bomb. v. iii, Your sonne Memphis, had a moale vnder his eare:.. you shall see it taken away with the iuyce of mandrage.

1601 Philemon Holland, translator Pliny’s History of the world, commonly called the Natural historie II. 235 In the digging vp of the root of Mandrage, there are some ceremonies obserued.

1607 Edward Topsell The history of foure-footed beasts and serpents (1658) 330 Oyl of Mandrag..bindeth together..bones being either shivered or broken.

1656 Blount Glossogr., Mandrake or Mandrage.

A. 1310 in Wright Lyric P. 26 Muge he is ant mondrake.

C. 1450 ME. Med. Bk. (Heinrich) 231 Leues of mandrake.

C. 1475 Pict. Voc. in Thomas Wright and Richard Paul Wülcker, Anglo-Saxon and Old English Vocabularies (1884) 787/4 Hec mandracora, a mandrak.

1560 Bible (Geneva) Gen. xxx. 14 Reuben… found mandrakes [marg. Which is a kinde of herbe, whose rote hath a certeine likenes of ye figure of a man] in the field.

1592 Shakspeare Romeo & Juliet iv. iii. 47 And shrikes like Mandrakes torne out of the earth.

1593 Shakspeare 2 Henry VI, iii. ii. 310.

1600 Heywood 2nd Pt. Edw. IV Wks. 1874 I. 154 The mandrakes shrieks are music to their cries.

1610 Donne Pseudo-martyr Pref. c iij, Annibal, to entrappe and surprise his enemies, mingled their wine with Mandrake, whose operation is betwixt sleepe and poyson.

1635 [Glapthorne] Lady Mother v. ii. in Bullen O. Pl. II. 196 Horrid grots and mossie graves, Where the mandraks hideous howles Welcome bodies voide of soules.

1712 tr. Pomet’s History of Drugs I. 80 The Mandrake is a Plant without a Stem.

1879 J. Timbs in Cassell’s Technical Education. IV. 106/1 The Greeks and the Romans used the root of the mandrake to cause insensibility to pain.

In allusive and fig. uses: (a) as a term of abuse; (b) a narcotic; (c) a noisome growth.

1508 Kennedie Flyting w. Dunbar 29 Mandrag, mymmerkin, maid maister bot in mowis. A.

1585 Montgomerie Flyting 71 Trot, tyke, to a tow, mandrage but myance.

1593 G. Harvey Pierce’s Super. Wks. (Grosart) II. 293 Correct the Mandrake of scurrility with the myrrhe of curtesie.

1597 Shakspeare 2 Henry IV, i. ii. 67 Thou horson Mandrake.

1604 Dekker Honest Wh. Wks. 1873 II. 9 Gods my life, hee’s a very mandrake.

1610 J. Mason Turk ii. i, Thou that amongst a hundred thousand dreames Crownd with a wreath of mandrakes sitst as Queene.

1636 Davenant Wits iv. i, He stands as if his Legs had taken root; A very Mandrake!

1649 Jer. Taylor Gt. Exemp. i. iv. 132 When we lust after mandrakes and deliciousness of exteriour ministries.

1660 R. L’Estrange Plea for Limited Monarchy 7 Our laws [sc. during the Commonwealth] have been Mandrakes of a Nights growth.

1676 Marvell Gen. Councils Wks. 1875 IV. 101 If they have a mind to pull up that mandrake, it were advisable..to chuse out a dog for that imployment.