Among people who finished their life high and short after a certain application of Pantagruelion.

Notes

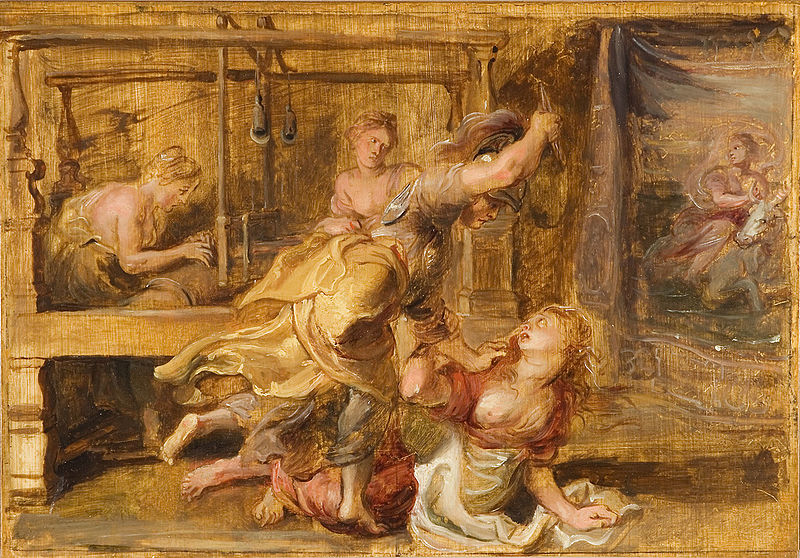

Pallas and Arachne

Arachne

Arachne

So saying, she [Pallas] turned her mind to the fate of Maeonian Arachne, who she had heard would not yield to her the palm in the art of spinning and weaving wool. Neither for place of birth nor birth itself had the girl fame, but only for her skill. Her father, Idmon of Colophon, used to dye the absorbent wool for her with Phocaean purple. Her mother was now dead; but she was low-born herself, and had a husband of the same degree. Nevertheless, the girl, Arachne, had gained fame for her skill throughout the Lydian towns, although she herself had sprung from a humble home and dwelt in the hamlet of Hypaepa. Often, to watch her wondrous skill, the nymphs would leave their own vineyards on Timolus’ slopes, and the water-nymphs of Pactolus would leave their waters. And ’twas a pleasure not alone to see her finished work, but to watch her as she worked; so graceful and deft was she. Whether she was winding the rough yarn into a new ball, or shaping the stuff with her fingers, reaching back to the distaff for more wool, fleecy as a cloud, to draw into long soft threads, or giving a twist with practised thumb to the graceful spindle, or embroidering with her needle: you could know that Pallas had taught her. Yet she denied it, and, offended at the suggestion of a teacher ever so great, she said: “Let her but strive with me; and if I lose there is nothing which I would not forfeit.”

Then Pallas assumed the form of an old woman, put false locks of grey upon her head, took a staff in her hand to sustain her tottering limbs, and thus she began: “Old age has some things at least that are not to be despised; experience comes with riper years. Do not scorn my advice: seek all the fame you will among mortal men for handling wool; but yield place to the goddess, and with humble prayer beg her pardon for your words, reckless girl. She will grant you pardon if you ask it.” But she regarded the old woman with sullen eyes, dropped the threads she was working, and, scarce holding her hand from violence, with open anger in her face she answered the disguised Pallas: “Doting in mind, you come to me, and spent with old age; and it is too long life that is your bane. Go, talk to your daughter-in-law, or to your daughter, if such you have. I am quite able to advise myself. To show you that you have done no good by your advice, we are both of the same opinion. Why does not your goddess come herself? Why does she avoid a contest with me?” Then the goddess exclaimed: “She has come!” and throwing aside her old woman’s disguise, she revealed Pallas. The nymphs worshipped her godhead, and the Mygdonian women; Arachne alone remained unafraid, though she did turn red, for a sudden flush marked her unwilling cheeks and again faded: as when the sky grows crimson when the dawn first appears, and after a little while when the sun is up it pales again. Still she persists in her challenge, and stupidly confident and eager for victory, she rushes on her fate. For Jove’s daughter refuses not, nor again warns her or puts off the contest any longer. They both set up the looms in different places without delay and they stretch the fine warp upon them…

Pallas pictures the hills of Mars on the citadel of Cecrops and that old dispute over the naming of the land…

Arachne pictures Europa cheated by the disguise of the bull…

Not Pallas, nor Envy himself, could find a flaw in that work. The golden-haired goddess was indignant at her success, and rent the embroidered web with its heavenly crimes; and, as she held a shuttle of Cytorian boxwood, thrice and again she struck Idmonian Arachne’s head. The wretched girl could not endure it, and put a noose about her bold neck. As she hung, Pallas lifted her in pity, and said: “Live on, indeed, wicked girl, but hang thou still; and let this same doom of punishment (that thou mayst fear for future times as well) be declared upon thy race, even to remote posterity.” So saying, as she turned to go she sprinkled her with the juices of Hecate’s herb; and forthwith her hair, touched by the poison, fell off, and with it both nose and ears; and the head shrank up; her whole body also was small; the slender fingers clung to her side as legs; the rest was belly. Still from this she ever spins a thread; and now, as a spider, she exercises her old-time weaver-art.

Arachné

Elle étoit habile dans l’art de broder; mais Minerve ayant brisé le métier et les fuseaux de sa rivale, elle se pendit de désespoir, et fut changée en araignée.

Arachne

Voy. Ovide, Metam. lib. VI.

Arachne

Ovid Met. vi 5-135.

Arachne

Sur le suicide d’Arachné, voir Ovide, Métamorphoses, VI, 5.

Arachne

Arachne, the skilful spinner, who, having challenged Minerva, lost, and had recourse to the rope, Minerva changing her, later, into a spider.

Arachné

Ovide, Métamorphoses, VI, v. 5.