The name of Pantagruel’s tutor Epistemon means wise or prudent in Greek. After the battle in which Pantagruel defeated Loup Garou of the Dipsodes, Epistemon was found with his head chopped off. Panurge joined nerve to nerve, vessel to vessel, and stitched his noggin back on. Epistemon awoke as though from a sleep. He belched, he coughed, he hiccuped, he farted. He related his visit to Hell, where the heroes of this life are menial laborers, and the simple philosophers live in luxury. Epistemon thereafter suffered a dry cough, of which he could only rid himself by drinking like a theologian.

Notes

Comment Panurge prend conseil de Epistemon. Chapter 24

Laissans la Villaumère, & retournans vers Pantagruel, par le chemin Panurge s’adressa à Epistemon, & luy dist.

Compère mon antique amy, vous voyez la perplexité de mon esprit. Vous sçavez tant de bons remèdes. Me sçauriez vous secourir?

Epistemon print le propous, & remonstroit Panurge comment la voix publicque estoit toute consommée en mocqueries de son desguisement: & luy conseilloit prendre quelque peu de Ellebore, affin de purger cestuy humeur en luy peccant, & reprendre ses accoustremens ordinaires.

Ie suys (dist Panurge) Epistemon mon compère, en phantasie de me marier. Mais ie crains estre coqu & infortuné en mon mariage. Pourtant ay ie faict veu à sainct François la ieune, lequel est au Plessis lez Tours reclamé de toutes femmes en grande devotion (car il est premier fondateur des bons hommes, lesquelz elles appetent naturellement) porter lunettes au bonnet, ne porter braguette en chausses, que sus ceste mienne perplexité d’esprit ie n’aye eu resolution aperte.

C’est (dist Epistemon) vrayment un beau & ioyeulx veu. Ie me esbahys de vous, que ne retournez à vous mesmes, & que ne revocquez vos sens de ce farouche esguarement en leur tranquillité naturelle. Vous entendent parler, me faictez souvenir du veu des Argives à la large perrucque, les quelz ayant perdu la bataille contre les Lacedaemoniens en la controverse de Tyrée, feirent veu: cheveux en teste ne porter, iusques à ce qu’ils eussent recouvert leur honneur & leur terre: du veu aussi du plaisant Hespaignol Michel Doris, qui porta le trançon de grève en sa iambe. Et ne sçay lequel des deux seroit plus digne & meritant porter chapperon verd & iausne à aureilles de lièvre, ou icelluy glorieux champion, ou Enguerrant qui en faict le tant long, curieux, & fascheux compte, oubliant l’art & manière d’escrire histoires, baillée par le philosophe Samosatoys. Car lisant icelluy long narré, l’on pesne que doibve estre commencement, & occasion de quelque forte guerre, ou insigne mutation des Royaulmes: mais en fin de compte on se mocque & du benoist champion, & de l’Angloys qui le deffia, & de Enguerrant leur tabellion: plus baveux qu’un pot à moustarde. La mocquerie est telle que de la montaigne d’Hiorace, laquelle crioyt & lamentoyt enormement, comme femme en travail d’enfant. A son cris & lamentation accourut tout le voisinaige en expectation de veoir quelque admirable & monstrueux enfantement, mais en fin ne nasquit d’elle qu’une petite souriz.

Non pourtant (dist Panurge) ie m’en soubrys. Se mocque qui clocque. Ainsi seray comme porte mon veu. Or long temps a que avons ensemble vous & moy, foy & amitié iurée, par Iuppiter Philios, dictez m’en vostre advis. Me doibz ie marier, ou non?

Certes (respondit Epistemon) le cas est hazardeux, ie me sens par trop insuffisant à la resolution. Et si iamais feut vray en l’art de medicine le dict du vieil Hippocrates de Lango, IUGEMENT DIFFICILE, il est cestuy endroict verissime. I’ay bien en imagination quelques discours moienans les quelz nous aurions determination sus vostre perplexité. Mais ilz ne me satisfont poinct apertement. Aulcuns Platonicques disent que qui peut veoir son Genius, peut entendre ses destinées. Ie ne comprens pas bien leur discipline, & ne suys d’advis que y adhaerez. Il y a de l’abus beaucoup. I’en ay veu l’expereince en un gentil home studieux & curieux on pays d’Estangourre. C’est le poinct premier. Un aultre y a. Si encores regnoient les oracles de Iuppiter en Mon: de Apollo en Lebadie, Delphes, Delos, Cyrrhe, Patare, Tegyres, Preneste, Lycie, Colophon: en la fontaine Castallie près Antioche en Syrie: entre les Branchides: de Bacchus, en Dodone: de Mercure, en Phares près Tatras: de Apis, en Aegypte: de Serapis, en Canobe: de Faunus, en Maenalie & en Albunée près Tivoli: de Tyresias, en Orchomène: de Mopsus, en Cilicie: de Orpheus, en Lesbos: de Trophonius, en Leucadie. Ie seroys d’advis (paradventure non seroys) y aller & entendre quel seroit leur iugement sus vostre entreprinse. Mais vous sçavez que tous sont devenuz plus mutz que poissons, depuys la venue de celluy Roy servateur, on quel ont prins fin tous oracles & toutes propheties: comme advenente la lumière du clair Soleil disparent tous Lutins, Lamies, Lemures, Guaroux, Farfadetz, & Tenebrions. Ores toutesfoys qu’encores feussent en règne, ne conseilleroys ie facillement adiouster foy à leurs responses. Trop de gens y ont esté trompez. D’adventaige mist sus à Lollie la belle, avoir interrogué l’oracle de Apollo Clarius pour entendre si mariée elle seroit avecques Claudius l’empereur. Pour ceste cause feut premierement banie, & depuys à mort ignominieusement mise.

Mais (dist Panurge) faisons mieulx. Les isles Ogygies ne sont loing du port Sammalo, faisons y un voyage après qu’aurons parlé à nostre Roy. En l’une des quatre, laquelle plus à son aspect vers Soleil couchant, on dict, ie l’ay leu en bons & antiques autheurs, habiter plusieurs divinateurs, vaticinateurs, & prophètes: y estre Saturne lié de belles chaines d’or, dedans une roche d’or, alimenté de Ambrosie & Nectar divin, les quelz iournellement luy sont des cieulx transmis en abondance par ne sçay quelle espèce d’oizeaulx (peut estre que sont les mesmes Corbeaulx, qui alimentoient es desers sainct Paul premier hermite) & apertement predire à un chascun qui veult entendre son sort, sa destinées, & ce que luy doibt advenir. Car les Parces rien ne sillent, Iuppiter rien ne propense & rien ne delibère, que le bon père en dormant ne congnoisse. Ce nous seroit grande abbreviation de labeur, si nous le oyons un peu sus ceste mienne perplexité.

C’est (respondit Epistemon) abus trop evident, & fable trop fabuleuse. Ie ne iray pas.

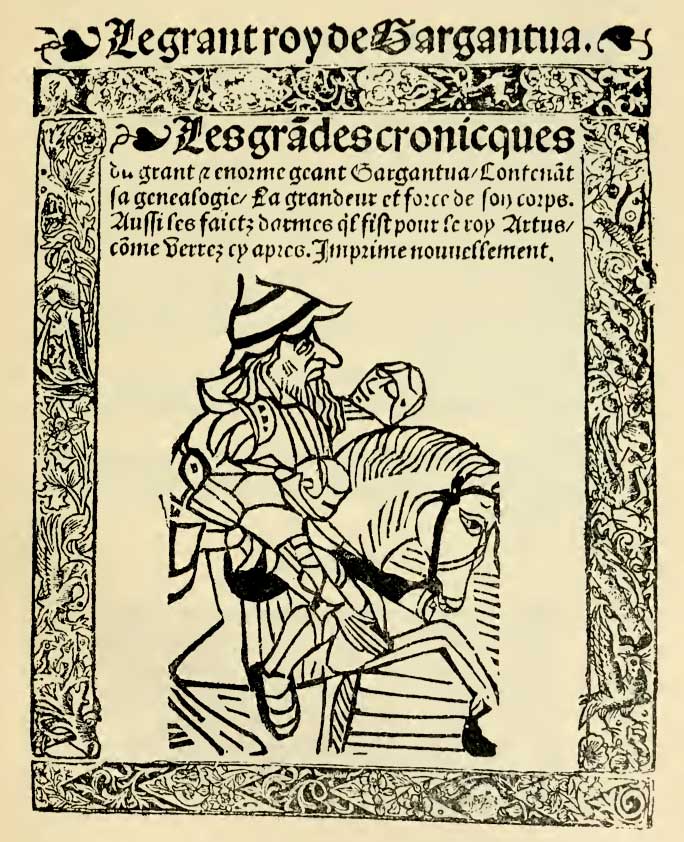

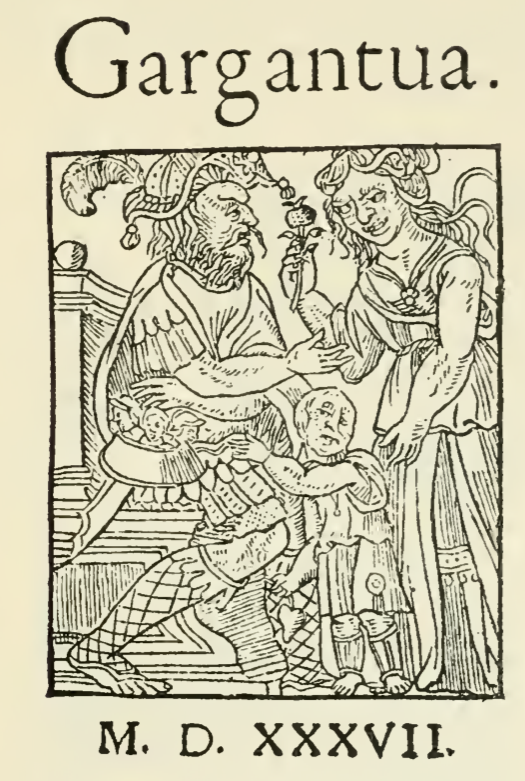

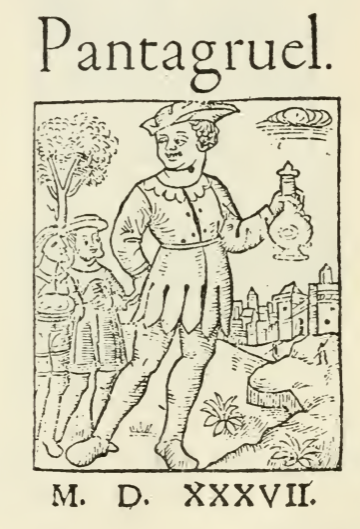

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553),

Le Tiers Livre des Faicts et Dicts Heroïques du bon Pantagruel: Composé par M. Fran. Rabelais docteur en Medicine. Reueu, & corrigé par l’Autheur, ſus la cenſure antique. L’Avthevr svsdict ſupplie les Lecteurs beneuoles, ſoy reſeruer a rire au ſoixante & dixhuytieſme Liure. Paris: Michel Fezandat, 1552. Chapter 24, p. 79.

Les Bibliotèques Virtuelles Humanistes

Chapter 24. How Panurge taketh Counsel of Epistemon

As they were leaving Villaumere and returning towards Pantagruel, on the way Panurge addressed himself to Epistemon, and said to him: “Gossip, my ancient Friend, you see the Perplexity of my Mind. And you know such a Number of good Remedies. Could you not succour me?”

Epistemon took up the Subject, and represented to Panurge how the common Talk was entirely taken up with Scoffings at his Disguise; wherefore he advised him to take a little Hellebore, in order to purge him of this peccant Humour, and to resume his ordinary Apparel.

“My dear Gossip Epistemon,” quoth Panurge, “I am in a Fancy to marry me, but I am afraid of being a Cuckold and unfortunate in my Marriage.

“Wherefore I have made a Vow to Saint Francis the Younger [1], who at Plessis-lez-Tours is in much Request and Devotion of all Women (for he is the first Founder of the Fraternity of Good Men, whom they naturally long for), to wear Spectacles in my Cap and to wear no Cod-piece on my Breeches, till I have a clear Settlement in the Matter of this my Perplexity of Mind.”

“’Tis indeed,” said Epistemon, “a rare merry Vow. I am astonished that you do not return to yourself and recall your Senses from this wild Straying abroad to their natural Tranquillity. “When I hear you talk thus, you remind me of the Vow of the Argives of the long Wig [2], who having lost the Battle against the Lacedaemonians in the Quarrel about Thyrea, made a Vow not to wear Hair on their Head till they had recovered their Honour and their Land; also of the Vow of the pleasant Spaniard Michael Doris, who ever carried the Fragment of Thigh-armour on his Leg.

” And I do not know whether of the two would be more worthy, and deserving to wear a green and yellow [3] Cap and Bells with Hare’s Ears, the aforesaid vainglorious Champion, or Enguerrant [4], who makes concerning it so long, painful and tiresome an Account, quite forgetting the proper Art and Manner of writing History, which is delivered by the Philosopher of Samosata [5] ; for in reading this long Narrative, one thinks it ought to be the Beginning and Occasion of some formidable War, or notable Change in Kingdoms. But at the End of the Story one only scoffs at the silly Champion, and the Englishman who defied him, as also at the Scribbler Enguerrant, who is a greater Driveller than a Mustard-pot.

“The Jest and Scorn thereof is like that of the Mountain in Horace [6], which cried out and lamented enormously, as a Woman in Travail of Child-birth. At its Cries and Lamentation the whole Neighbourhood ran together, in expectation to see some marvellous and monstrous Birth, but at last there was born of it nought but a little Mouse.”

“For all your mousing,” said Panurge, “I do not smile[7] at it ‘Tis the Lame makes game [8]. I shall do as my Vow impels me. Now it is a long Time since you and I together did swear Faith and Friendship by Jupiter Philios. Tell me, then, your Opinion thereon ; ought I to marry or not ? ”

“Verily,” replied Epistemon, “the Case is hazardous; I feel myself far too insufficient to resolve it; and if ever in the Art of Medicine the dictum of the old Hippocrates [9] of Lango [10], that ‘Judgment is difficult,’ was true, it is certainly most true in this Case.

“I have indeed in my Mind some Discourses, by means of which we could get a Determination on your Perplexity ; but they do not satisfy me clearly.

“Some Platonists declare that the Man who can see his Genius can understand his Destinies [11]. I do not understand their Doctrine, and am not of Opinion that you should give your Adhesion to them; there is much Error in it. I have seen it tried in the case of a studious and curious Gentleman in the Country of Estangourre [12]. That is Point the first.

” There is also another Point. If there were still any Authority in the Oracles

- of Jupiter in Ammon,

- of Apollo in Lebadia, Delphi, Delos, Cyrrha, Patara, Tegyra, Praeneste [13], Lycia, Colophon ; at the Fountain of Castalia, near Antioch [14] in Syria, among the Branchidae [15];

- of Bacchus in Dodona [16],

- of Mercury at Pharae near Patras,

- of Apis in Egypt,

- of Serapis at Canopus,

- of Faunus in Maenalia and at Albunea near Tivoli,

- of Tiresias at Orchomenus,

- of Mopsus [17] in Cilicia,

- of Orpheus in Lesbos,

- of Trophonius in Leucadia [18],

I should be of Opinion — perhaps I should not — that you should go thither and hear what would be their Judgment on your present Enterprise.

“But you know that they have all become more [19] dumb than Fishes since the Coming of that Saviour King, what time all Oracles and all Prophecies made an End; as when, on the Approach of the Light of the radiant Sun, all Spectres, Lamiae, Spirits, Ware-wolves, Hobgoblins and Dung-beetles disappear. Moreover, even though they were still in vogue, I should not counsel you to put Faith in their Responses too readily. Too many Folks have already been deceived thereby.

“Besides, I remember to have read that [20] Agrippina put upon the fair Lollia the Charge of having interrogated the Oracle of Apollo Clarius, to learn if she should ever be married to the Emperor Claudius; and for this Reason she was first banished, and afterwards ignominiously put to Death.”

“But,” said Panurge, “let us do better. The Ogygian [21] Islands are not far from the Harbour of St. Malo. Let us make a Voyage thither after we have spoken to our King on the Subject.

“In one of the four which hath its Aspect more turned towards the Sunset, it is reported — I have read it in good and ancient Authors — that there dwell several Soothsayers, Vaticinators and Prophets; that Saturn [22] is there bound with fine Chains of Gold, within a Cave of a golden Rock, nourished with divine Ambrosia and Nectar, which are daily transmitted in abundance to him from the Heavens by I know not what kind of Birds — it may be, they are the same Ravens which fed St Paul [23], the first Hermit, in the Desert — and that he clearly foretells to every one who wishes to hear, his Lot, his Destiny and that which must happen to him ; for the Fates spin nothing, Jupiter projects nothing, deliberates nothing, which the good Father knoweth not in his Sleep. It would be a great Abbreviation of Labour for us, if we should hearken a little to him on this Perplexity of mine.”

“That is,” replied Epistemon, “an Imposture too evident, and a Fable too fabulous. I will not go.”

Smith’s notes

1. St. Francis de Paule, to distinguish him from St. Francis of Assisi. He had been surnamed le bon homme by Louis XI., and consequently the Minims founded by him, had obtained this name. Cf. iii. 22, n.3. Their first cloister was founded at Plessis-les-Tours, of which Scott speaks often in Quentin Durward. Duchat points out that lepers also were called les bons hommes in France, as being lecherous.

2. Herodotus i. 82

3. The colours, etc., of the fool’s dress in the middle ages.

4. Enguerrant de Monstrelet, governor of Cambray, continuer of Froissart’s history from 1400 to 1467, in the second Book of his Chronicles tells the Story in many pages how the Spaniard Michael d’Oris and an Englishman named Prendergast defied one another, and went backwards and forwards many times, and it all came to nothing.

5. Lucian, de histor. conscrib.

6. Parturiunt monies, nascetur ridiculus mus. Hor. A.P. 139.

7. The pun of souris (mouse) and soubris (smile) occurs in the following extract :

Sire Lyon (dit le fils de souriz)

de ton propos certes je me soubriz.

— Cl. Marot, Epistre à son ami Lyon (xi. 1. 55).

8. Loripedem rectus derideat, Aethiopem albus.

—Juv. ii. 23.

9. In this sentence of Epistemon there are two quotations from the first aphorism of Hippocrates.

10. Lango is the modern name of Cos, the birthplace of Hippocrates.

11. In answer to Porphyrius, lamblichus writes: [greek text] (de Myst. ix. 3) Cf. Serv. ad Aen. vi. 743.

12. Estrangourre, or Estangor, as it occurs in the Romance of Lancelot du Lac, is East Anglia, one of the divisions of the Saxon Heptarchy.

13. Praeneste. It is to Fortuna and not to Apollo that the temple here is dedicated, and it was especially the sortes Praenestinae that were celebrated as prophetic. Cf. Cic. de Div. ii. 41, §§ 86, 87.

14. Antioch. The reference is to a celebrated grove and sanctuary of Apollo called Daphne, near Antioch (Josephus, B. J. i. 12 § 5; and others.

15. Branchidae. The temple of Apollo at Didymi, at Branchidae in the Milesian territory, is mentioned by Herodotus (i. 46, 92, etc.); Strabo, p. 634; Pausanias, vii. 2, § 5; and others.

16. There was no special oracle of Bacchus at Dodona.

17. Mopsus, son of Manto, daughter of Tiresias.

18. Leucadia should be Lebadeia in Boeotia. Trophonius was the architect of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, and after his death was worshipped as a hero. He had a celebrated oracle in a cave at Lebadeia (v . 36). Cf. Herod., i. 46; Pausanias, ix. 37-39 ; Aristoph. Nub. 508.

19. Cf. Plutarch de orac. def. and v. 47, n. 2.

20. Tac. Ann. xii. 22.

21. The island of Ogygia is Calypso’s island in the Odyssey, and according to Homer (Od. v. 280) is eighteen days’ voyage from the island of the Phaeacians in the far north-west. According to Plutarch (de facie in orbe Lunae, c. 26 941 A), it is five days’ sail from Great Britain to the west, and there are three other islands equally distant from it and each other, in one of which Saturn is chained. Motteux conjectures with probability that the Channel Islands are intended by Rabelais. The legend is employed by Keats at the beginning of his Hyperion.

22. Plut. de fac. in orb. Lun. c. 26, 942 A.

23. The allusion is not to the apostle but to the hermit St. Paul, who is said to have lived in the time of the Emperor Decius, and to have been fed by ravens. Cf. Legenda Aurea, cap. xv.

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893. p. 484.

Internet Archive

Epistemon

Les premiers textes de la base « Epistemon » ont été mis en ligne en 1998 à l’Université de Poitiers, puis à l’université François-Rabelais de Tours (Centre d’Etudes Supérieures de la Renaissance) dès 2001.

La première base a d’abord offert des textes transcrits et publiés au format html avec des modifications minimales, comme pour le corpus « Rabelais » publié en ligne depuis 1995 par Etienne Brunet et Marie-Luce Demonet sur le site Rabelais de l’Université de Nice, maintenant inactif.