Rabelais and Pliny

The Roman author Pliny the Elder (born Gaius Plinius Secundus, AD 23 – 79) wrote the encyclopedic Naturalis Historia (Natural History).

In the chapters on Pantagruelion, Rabelais embellished Pliny’s treatment of flax in book 19 of Natural History,[1] and cast it in a different light.

Rabelais mentioned Pliny in Chapter 13 of the Le Tiers Livre, among the authorities cited in defense of divination by dreams, a method “good, ancient, and authentic.”[2]

“Even so our Soul, when the Body sleeps and the Digestion is in all Parts completed, nothing being necessary till the Waking up, takes its Pastime and revisits its native Country, which is Heaven.”[3]

1. Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD), The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.1. Loeb Classical Library

2. Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Le Tiers Livre des Faicts et Dicts Heroïques du bon Pantagruel: Composé par M. Fran. Rabelais docteur en Medicine. Reueu, & corrigé par l’Autheur, ſus la cenſure antique. L’Avthevr svsdict ſupplie les Lecteurs beneuoles, ſoy reſeruer a rire au ſoixante & dixhuytieſme Liure. Paris: Michel Fezandat, 1552. Ch. 13. Les Bibliotèques Virtuelles Humanistes

3. Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 2: Books IV-V and minor writings. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893. p. 435

. Internet Archive

Notes

Pliny 19.1

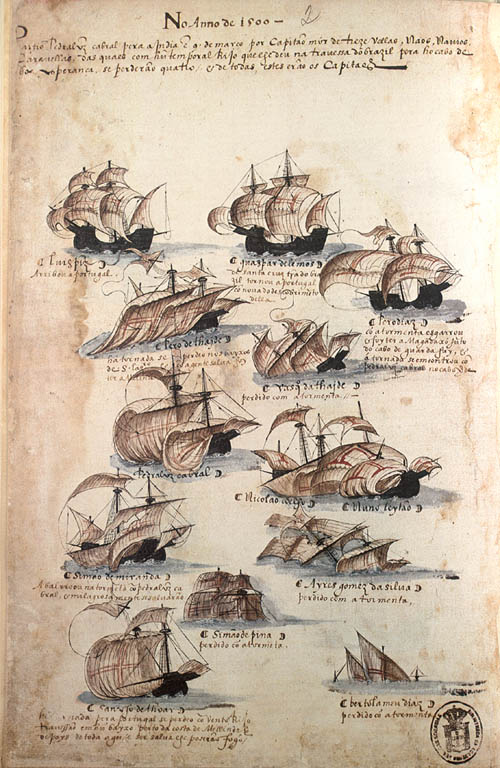

Siderum quidem tempestatumque ratio vel imperitis facilis atque indubitata modo demonstrata est; vereque intellegentibus non minus conferunt rura deprehendendo caelo quam sideralis scientia agro colendo. proximam multi hortorum curam fecere; nobis non protinus transire ad ista tempestivum videtur, miramurque aliquos scientiae gratiam eruditionisve gloriam ex his petentes tam multa praeterisse nulla mentione habita tot rerum sponte curave provenientium, praesertim cum plerisque earum pretio usuque vitae maior etiam quam frugibus perhibeatur auctoritas. atque, ut a confessis ordiamur utilitatibus quaeque non solum terras omnes verum etiam maria replevere, seritur ac dici neque inter fruges neque inter hortensia potest linum; sed in qua non occurret vitae parte, quodve miraculum maius, herbam esse quae admoveat Aegyptum Italiae in tantum ut Galerius a freto Siciliae Alexandriam septimo die pervenerit, Balbillus sexto, ambo praefecti, aestate vero post xv annos Valerius Marianus ex praetoriis senatoribus a Puteolis nono die lenissumo flatu? herbam esse quae Gades ab Herculis columnis septimo die Ostiam adferat et citeriorem Hispaniam quarto, provinciam Narbonensem tertio, Africam altero, quod etiam mollissumo flatu contigit C. Flavio legato Vibii Crispi procos.? audax vita, scelerum plena, aliquid seri ut ventos procellasque capiat, et parum esse fluctibus solis vehi, iam vero nec vela satis esse maiora navigiis, sed, quamvis vix amplitudini velorum antemnarum singulae arbores sufficiant, super eas tamen addi alia vela praeterque alia in proris et alia in puppibus pandi, ac tot modis provocari mortem, denique e tam parvo semine nasci quod orbem terrarum ultro citro portet, tam gracili avena, tam non alte a tellure tolli, neque id viribus suis nexum, sed fractum tunsumque et in mollitiem lanae coactum iniuria ad summa audaciae pervenire. nulla exsecratio sufficit contra inventorem dictum suo loco a nobis, cui satis non fuit hominem in terra mori nisi periret et insepultus. at nos priore libro imbres et flatus cavendos frugum causa victusque praemonebamus: ecce seritur hominis manu, nectitur eiusdem hominis ingenio quod ventos in mari optet! praeterea, ut sciamus favisse Poenas, nihil gignitur facilius, ut sentiamus nolente seri natura, urit agrum deterioremque etiam terram facit.

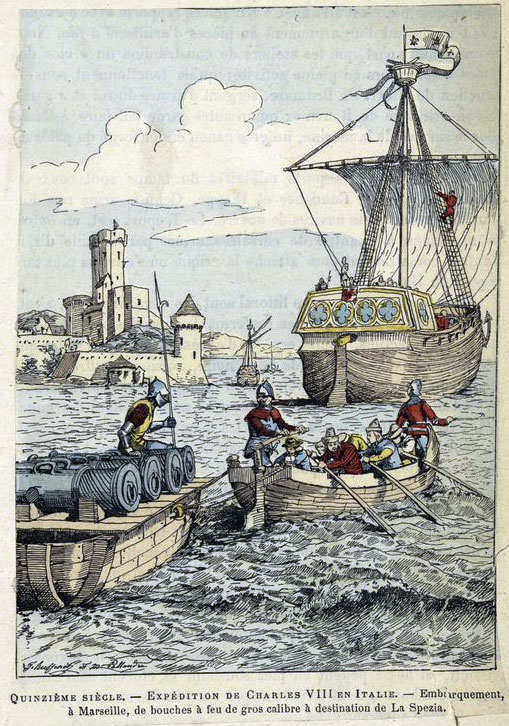

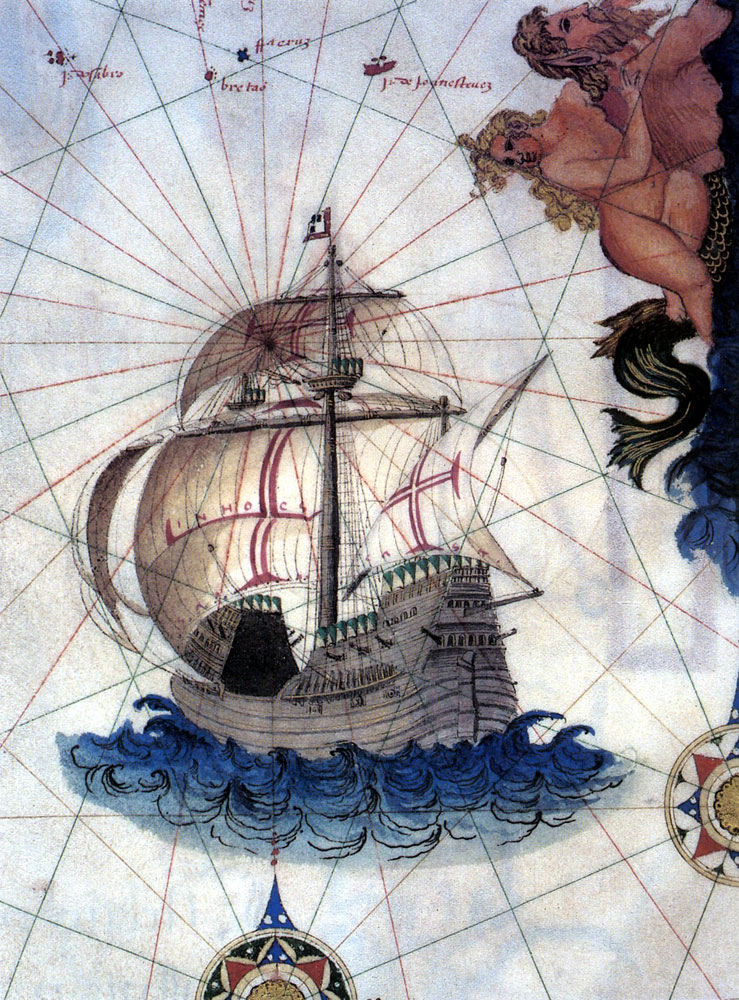

An account of the constellations, seasons and weather has now been given that is easy even for non-experts to understand does not leave any room for doubt; and for those who really understand the matter the countryside contributes to our knowledge of the heavens no less than astronomy contributes to agriculture. Many writers have made horticulture [This refers to kitchen-gardens, not to flower-gardens] the next subject; we however do not think the time has come to pass straight to those topics, and we are surprised that some persons seeking from these subjects the satisfaction of knowledge, or a reputation for learning, have passed over so many matters without making any mention of all the plants that grow of their own accord or from cultivation, especially in view of the fact that even greater importance attaches to very many of these, in point of price and of practical utility, than to the cereals. And to begin with admitted utilities and with commodities distributed not only throughout all lands but also over the seas: flax is a plant that is grown from seed and that cannot be included either among cereals or among garden plants; but in what department of life shall we not meet with it, or what is more marvellous than the fact that there is a plant which brings Egypt so close to Italy that of two governors of Egypt Galerius reached Alexandria from the Straits of Messina in seven days and Balbillus in six, and that in the summer [AD 55] 15 years later the praetorian senator Valerius Marianus made Alexandria from Pozzuoli in nine days with a very gentle breeze? or that there is a plant that brings Cadiz within seven days’ sail from the Straits of Gibraltar to Ostia, and Hither Spain within four days, and the Province of Narbonne within three, and Africa within two? The last record was made by Gaius Flavius, deputy of the proconsul Vibius Crispus, even with a very gentle wind blowing. How audacious is life and how full of wickedness, for a plant to be grown for the purpose of catching the winds and the storms, and for us not to be satisfied with being borne on by the waves alone, nay that by this time we are not even satisfied with sails that are larger than ships, but, although single trees are scarcely enough for the size of the yard-arms that carry the sails, nevertheless other sails are added above the yards and others besides are spread at the bows and others at the sterns, and so many methods are employed of challenging death, and finally that out of so small a seed springs a means of carrying the whole world to and fro, a plant with so slender a stalk and rising to such a small height from the ground, and that this, not after being woven into a tissue by means of its natural strength but when broken and crushed and reduced by force to the softness of wool, afterwards by this ill-treatment attains to the highest pitch of daring! No execration is adequate for an inventora in navigation (whom we mentioned above in the proper place), who was not content that mankind should die upon land unless he also perished where no burial awaits him. Why, in the preceding Book [XVIII. 326 ff] we were giving a warning to beware of storms of rain and wind for the sake of the crops and of our food: and behold man’s hand is engaged in growing and likewise his wits in weaving an object which when at sea is only eager for the winds to blow! And besides, to let us know how the Spirits of Retribution have favoured us, there is no plant that is grown more easily; and to show us that it is sown against the will of Nature, it scorches the land and causes the soil actually to deteriorate in quality.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.1.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.2

II. Seritur sabulosis maxime unoque sulco. nec magis festinat aliud: vere satum aestate evellitur, et hanc quoque terrae iniuriam facit. ignoscat tamen aliquis Aegypto serenti ut Arabiae Indiaeque merces inportet: itane et Galliae censentur hoc reditu? montesque mari oppositos esse non est satis et a latere oceani obstare ipsum quod vocant inane? Cadurci, Caleti, Ruteni, Bituriges ultumique hominum existimati Morini, immo vero Galliae universae vela texunt, iam quidem et transrhenani hostes, nec pulchriorem aliam vestem eorum feminae novere. qua admonitione succurrit quod M. Varro tradit, in Serranorum familia gentilicium esse feminas lintea veste non uti. in Germania autem defossae atque sub terra id opus agunt; similiter etiam in Italiae regione Aliana inter Padum Ticinumque amnes, ubi a Saetabi tertio in Europa lino palma, secundam enim vicina Alianis capessunt Retovina et in Aemilia via Faventina. candore Alianis semper crudis Faventina praeferuntur, Retovinis tenuitas summa densitasque, candor qui Faventinis, sed lanugo nulla, quod apud alios gratiam, apud alios offensionem habet. nervositas filo aequalior paene quam araneis tinnitusque cum dente libeat experiri; ideo duplex quam ceteris pretium.

Et ab his Hispania citerior habet splendorem lini praecipua torrentis in quo politur natura, qui adluit Tarraconem; et tenuitas mira ibi primum carbasis repertis. non dudum ex eadem Hispania Zoelicum venit in Italiam plagis utilissimum; civitas ea Gallaeciae et oceano propinqua. est sua gloria et Cumano in Campania ad piscium et alitum capturam, eadem et plagis materia: neque enim minores cunctis animalibus insidias quam nobismet ipsis lino tendimus. sed Cumanae plagae concidunt apro saetas et vel ferri aciem vincunt, vidimusque iam tantae tenuitatis ut anulum hominis cum epidromis transirent, uno portante multitudinem qua saltus cingeretur. nec id maxume mirum, sed singula earum stamina centeno quinquageno filo constare, sicut paulo ante Fulvio Lupo qui in praefectura Aegypti obiit. mirentur hoc ignorantes in Agypti quondam regis quem Amasim vocant thorace in Rhodiorum insula Lindi in templo Minervae ccclxv filis singula fila constare, quod se expertum nuperrime prodidit Mucianus ter cos., parvasque iam reliquias eius superesse hoc1 experientium iniuria. Italia et Paelignis etiamnum linis honorem habet, sed fullonum tantum in usu; nullum est candidius lanaeve similius, sicut in culcitis praecipuam gloriam Cadurci obtinent: Galliarum hoc et tomenta pariter inventum. Italiae quidem mos etiam nunc durat in appellatione stramenti. Aegyptio lino minimum firmitatis, plurimum lucri. quattuor ibi genera: Taniticum, Pelusiacum, Buticum, Tentyriticum regionum nominibus in quibus nascuntur. superior pars Aegypti in Arabiam vergens gignit fruticem quem aliqui gossypion vocant, plures xylon et ideo lina inde facto xylina. parvus est similemque barbatae nucis fructum defert cuius ex interiore bombyce lanugo netur. nec ulla sunt cum candore molliora pexiorave. vestes inde sacerdotibus Aegypti gratissumae. quartum genus othoninum appellant; fit e palustri velut harundine, dumtaxat panicula eius. Asia e genista facit lina ad retia praecipue in piscando durantia, frutice madefacto x diebus, Aethiopes Indique e malis, Arabes e curcurbitis in arboribus, ut diximus, genitis.

II. Flax is chiefly grown in sandy soils, and with a single ploughing. No other plant grows more quickly: it is sown in spring and plucked in summer, and owing to this also it does damage to the land. Nevertheless, one might forgive Egypt for growing it to enable her to import the merchandise of Arabia and India. Really? And are the Gallic provinces also assessed on such revenue as this? And is it not enough that they have the mountains separating them from the sea, and that on the side of the ocean they are bounded by an actual vacuum [I.e. the Atlantic ocean is mere emptiness, τὸ κενόν of the philosophers], as the term is? The Cadurci, Caleti, Ruteni, Bituriges, and the Morini who are believed to be the remotest of mankind, in fact the whole of the Gallic provinces, weave sailcloth, and indeed by this time so do even our enemies across the Rhine, and linen is the showiest dress-material known to their womankind. This reminds us of the fact recorded by Varro that it is a clan-custom in the family of the Serrani for the women not to wear linen dresses. In Germany the women carry on this manufacture in caves dug underground [The humidity was supposed to be favourable to the manufacture of the tissue]; and similarly also in the Alia district of Italy between the Po and the Ticino, where the linen wins the prize as the third best in Europe, that of Saetabis being first, as the second prize is won by the linens of Retovium near the Alia district and Faenza on the Aemilian Road. The Faenza linens are preferred for whiteness to those of Alia, which are always unbleached, but those of Retovium are supremely fine in texture and substance and are as white as the Faventia, but have no nap, which quality counts in their favour with some people but puts off others. This flax makes a tough thread having a quality almost more uniform than that of a spider’s web, and giving a twang when you choose to test it with your teeth; consequently it is twice the price of the other kinds.

And after these it is Hither Spain that has a linen of special lustre, due to the outstanding quality of a stream that washes the city of Tarragon, in the waters of which it is dressed; also its fineness is marvellous, Tarragon being the place where cambrics were first invented. From the same province of Spain Zoëla flax has recently been imported into Italy, a flax specially useful for hunting-nets; Zoëla is a city of Gallaecia near the Atlantic coast. The flax of Cumae in Campania also has a reputation of its own for nets for fishing and fowling, and it is also used as a material for making hunting-nets: in fact we use flax to lay no less insidious snares for the whole of the animal kingdom than for ourselves! But the Cumae nets will cut the bristles of a boar and even turn the edge of a steel knife; and we have seen before now netting of such fine texture that it could be passed through a man’s ring, with running tackle and all, a single person carrying an amount of net sufficient to encircle a wood! Nor is this the most remarkable thing about it, but the fact that each string of these nettings consists of 150 threads, as recently made for Fulvius Lupus who died in the office of governor of Egypt. This may surprise people who do not know that in a breastplate that belonged to a former king of Egypt named Amasis, preserved in the temple of Minerva at Lindus on the island of Rhodes, each thread consisted of 365 separate threads, a fact which Mucianus, who held the consulship three times quite lately, stated that he had proved to be true by investigation, adding that only small remnants of the breastplate now survive owing to the damage done by persons examining this quality. Italy also values the Pelignian flax as well, but only in its employment by fullers—no flax is more brilliantly white or more closely resembles wool; and similarly the flax grown at Cahors has a special reputation for mattresses: this use of it is an invention of the provinces of Gaul, as likewise is flock. As for Italy, the custom even now survives in the word [Stramentum, straw strewn to sleep on: cf. our paillasse, ‘bed of straw’] used for bedding. Egyptian flax is not at all strong, but it sells at a very good price. There are four kinds in that country, Tanitic, Pelusiac, Butic and Tentyritic, named from the districts where they grow. The upper part of Egypt, lying in the direction of Arabia, grows a bush which some people call cotton, but more often it is called by a Greek work meaning ‘wood’: hence the name xylina given to linens made of it. It is a small shrub, and from it hangs a fruit resembling a bearded nut, with an inner silky fibre from the down of which thread is spun. No kinds of thread are more brilliantly white or make a smoother fabric than this. Garments made of it are very popular with the priests of Egypt. A fourth kind is called othoninum; it is made from a sort of reed growing in marshes, but only from its tuft. Asia makes a thread out of broom, of which specially durable fishing-nets are made, the plant being soaked in water for ten days; the Ethiopians and Indians make thread from apples, and the Arabians from gourds that grow on trees, as we said [XII. 38].

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.2.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.3

III. Apud nos maturitas eius duobus argumentis intellegitur, intumescente semine aut colore flavescente. tum evolsum et in fasciculos manuales colligatum siccatur in sole pendens conversis superne radicibus uno die, mox quinque aliis contrariis in se fascium cacuminibus, ut semen in medium cadat. inter medicamina huic vis et in quodam rustico ac praedulci Italiae transpadanae cibo, sed iam pridem sacrorum tantum, gratia. deinde post messem triticiam virgae ipsae merguntur in aquam solibus tepefactam, pondere aliquo depressae, nulli enim levitas maior. maceratas indicio est membrana laxatior, iterumque inversae ut prius sole siccantur, mox arefactae in saxo tunduntur stuppario malleo. quod proximum cortici fuit, stuppa appellatur, deterioris lini, lucernarum fere luminibus aptior; et ipsa tamen pectitur ferreis aculeis donec omnis membrana decorticetur. medullae numerosior distinctio candore, mollitia; cortices quoque decussi clibanis et furnis praebent usum. ars depectendi digerendique—iustum a quinquagenis fascium libris … quinas denas carminari—linumque nere et viris decorum est; iterum deinde in filo politur, inlisum crebro silici ex aqua, textumque rursus tunditur clavis, semper iniuria melius.

III. With us the ripeness of flax is ascertained by two indications, the swelling of the seed or its assuming a yellowish colour. It is then plucked up and tied together in little bundles each about the size of a handful, hung up in the sun to dry for one day with the roots turned upward, and then for five more days with the heads of the bundles turned inward towards each other so that the seed may fall into the middle. Linseed makes a potent medicine; it is also popular in a rustic porridge with an extremely sweet taste, made in Italy north of the Po, but now for a long time only used for sacrifices. When the wheat-harvest is over the actual stalks of the flax are plunged in water that has been left to get warm in the sun, and a weight is put on them to press them down, as flax floats very readily. The outer coat becoming looser is a sign that they are completely soaked, and they are again dried in the sun, turned head downwards as before, and afterwards when thoroughly dry they are pounded on a stone with a tow-hammer. The part that was nearest the skin is called oakum—it is flax of an inferior quality, and mostly more fit for lampwicks; nevertheless this too is combed with iron spikes until all the outer skin is scraped off. The pith has several grades of whiteness and softness, and the discarded skin is useful for heating ovens and furnaces. There is an art of combing out and separating flax: it is a fair amount for fifteen [The text seems defective, a plural noun having been lost] to be carded out from fifty pounds’ weight of bundles; and spinning flax is a respectable occupation even for men. Then it is polished in the thread a second time, after being soaked in water and repeatedly beaten out against a stone, and it is woven into a fabric and then again beaten with clubs, as it is always better for rough treatment.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.3.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.4

IV. Inventum iam est etiam quod ignibus non absumeretur. vivum id vocant, ardentesque in focis conviviorum ex eo vidimus mappas sordibus exustis splendescentes igni magis quam possent aquis. regum inde funebres tunicae corporis favillam ab reliquo separant cinere. nascitur in desertis adustisque Indiae locis, ubi non cadunt imbres, inter diras serpentes, adsuescitque vivere ardendo, rarum inventu, difficile textu propter brevitatem; rufus de cetero colos splendescit igni. cum inventum est, aequat pretia excellentium margaritarum. vocatur autem a Graecis ἀσβέστινον ex argumento naturae suae. Anaxilaus auctor est linteo eo circumdatam arborem surdis ictibus et qui non exaudiantur caedi. ergo huic lino principatus in toto orbe. proximus byssino, mulierum maxime deliciis circa Elim in Achaia genito; quaternis denaris scripula eius permutata quondam ut auri reperio. linteorum lanugo, e velis navium maritimarum maxime, in magno usu medicinae est, et cinis spodii vim habet. est et inter papavera genus quoddam quo candorem lintea praecipuum trahunt.

IV. Also a linen has now been invented that is incombustible. It is called ‘live’ linen, and I have seen napkins made of it glowing on the hearth at banquets and burnt more brilliantly clean by the fire than they could be by being washed in water. This linen is used for making shrouds for royalty which keep the ashes of the corpse separate from the rest of the pyre. The plant [It is really the mineral asbestos] grows in the deserts and sun-scorched regions of India where no rain falls, the haunts of deadly snakes, and it is habituated to living in burning heat; it is rarely found, and is difficult to weave into cloth because of its shortness; its colour is normally red but turns white by the action of fire. When any of it is found, it rivals the prices of exceptionally fine pearls. The Greek name for it is asbestinon [‘Inextinguishable’], derived from its peculiar property. Anaxilaus states that if this linen is wrapped round a tree it can be felled without the blows being heard, as it deadens their sound. Consequently this kind of linen holds the highest rank in the whole of the world. The next place belongs to a fabric made of fine flax grown in the neighbourhood of Elis in Achaia, and chiefly used for women’s finery; I find that it formerly changed hands at the price of gold, four denarii for one twenty-fourth of an ounce. The nap of linen cloths, principally that obtained from the sails of sea-going ships, is much used as a medicine, and its ash has the efficacy of metal dross. Among the poppies also there is a kind from which an outstanding material for bleaching linen is extracted.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.4.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.5

V. Temptatum est tingui linum quoque, ut vestium insaniam acciperet, in Alexandri Magni primum classibus Indo amne navigantis, cum duces eius ac praefecti certamine quodam variassent et insignia navium, stupueruntque litora flatu versicoloria pellente. velo purpureo ad Actium cum M. Antonio Cleopatra venit eodemque fugit. hoc fuit imperatoriae navis insigne postea.

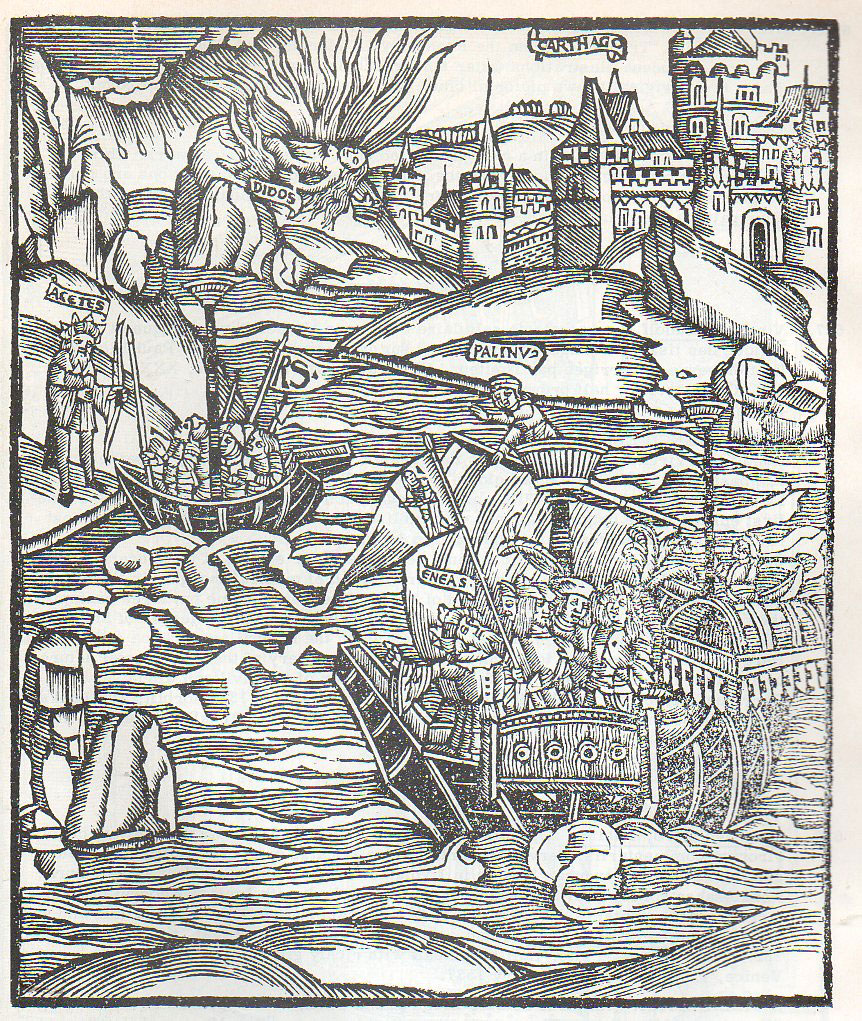

An attempt has been made to dye even linen ensigns and sails. so as to adapt it for our mad extravagance in clothes. This was first done in the fleets of Alexander the Great when he was voyaging on the river Indus, his generals and captains having held a sort of competition even in the various colours of the ensigns of their ships; and the river banks gazed in astonishment as the breeze filled out the bunting with its shifting hues. Cleopatra had a purple sail when she came with Mark Antony to Actium, and with the same sail she fled. A purple sail was subsequently the distinguishing mark of the emperor’s ship.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.5.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.6

VI. In theatris tenta umbram fecere, quod primus omnium invenit Q. Catulus cum Capitolium dedicaret. carbasina deinde vela primus in theatro duxisse traditur Lentulus Spinther Apollinaribus ludis. mox Caesar dictator totum forum Romanum intexit viamque sacram ab domo sua et clivum usque in Capitolium, quod munere ipso gladiatorio mirabilius visum tradunt. deinde et sine ludis Marcellus Octavia Augusti sorore genitus in aedilitate sua avunculi xi consulatu a kal. Aug. velis forum inumbravit, ut salubrius litigantes consisterent, quantum mutati a moribus Catonis censorii qui sternendum quoque forum muricibus censuerat! vela nuper et colore caeli, stellata, per rudentes iere etiam in amphitheatris principis Neronis. rubent in cavis aedium et muscum ab sole defendunt; cetero mansit candori pertinax gratia. honor ei iam1 et Troiano bello—cur enim non et proeliis intersit ut naufragiis? thoracibus lineis paucos tamen pugnasse testis est Homerus. hinc fuisse et navium armamenta apud eundem interpretantur eruditiores, quoniam, cum σπαρτὰ dixit, significaverit sata.

VI. Linen cloths were used in the theatres as awnings, a plan first invented by Quintus Catulus when dedicating the Capitol. Next Lentulus Spinther is recorded to have been the first to stretch awnings of cambric in the theatre, at the games of Apollo. Soon afterwards Caesar when dictator [49–44 B.C.] stretched awnings over the whole of the Roman Forum, as well as the Sacred Way from his mansion, and the slope right up to the Capitol, a display recorded to have been thought more wonderful even than the show of gladiators which he gave. Next even when there was no display of games Marcellus the son of Augustus’s sister Octavia, during his period of office as aedile, in the eleventh consulship of his uncle [23 B.C.], from the first of August onward fixed awnings of sailcloth over the forum, so that those engaged in lawsuits might resort there under healthier conditions: what a change this was from the stern manners of Cato the ex-censor, who had expressed the view that even the forum ought to be paved with sharp pointed stones! Recently awnings actually of sky blue and spangled with stars have been stretched with ropes even in the emperor Nero’s amphitheatres. Red awnings are used in the inner courts of houses and keep the sun off the moss growing there; but for other purposes white has remained persistently in favour. Moreover as early as the Trojan war linen already held a place of honour—for why should it not be present even in battles as it is in shipwrecks? Homer [Il. II. 529, 830] testifies that warriors, though only a few, fought in linen corslets. This material was also used for rigging ships, according to the same author as interpreted by the more learned scholars, who say that the word sparta used by Homer means ‘sown’.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.6.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.7

VII. Sparti quidem usus multa post saecula coeptus est, nec ante Poenorum arma quae primum Hispaniae intulerunt. herba et haec, sponte nascens et quae non queat seri, iuncusque proprie aridi soli, uni terrae data2 vitio: namque id malum telluris est, nec aliud ibi seri aut nasci potest. in Africa exiguum et inutile gignitur. Carthaginiensis Hispaniae citerioris portio, nec haec tota sed quatenus parit, montes quoque sparto operit. hinc strata rusticis eorum, hinc ignes facesque, hinc calceamina et pastorum vestes; animalibus noxium praeterquam cacuminum teneritate. ad reliquos usus laboriose evellitur ocreatis cruribus manuque textis manicis convoluta, osseis iligneisve conamentis, nunc iam in hiemem iuxta, facillime tamen ab idibus Maiis in Iunias: hoc maturitatis tempus.

VII. As a matter of fact the employment of espartoaFabrics of esparto. began many generations later, and not before the first invasion of Spain by the Carthaginians [237 b.c]. Esparto also is a plant, which is self-sown and cannot be grown from seed; strictly it is a rush, belonging to a dry soil, and all the blame for it attaches to the earth, for it is a curse of the land, and nothing else can be grown or can spring up there. In Africa it makes a small growth and is of no use. In the Cartagena section of Hither Spain, and not the whole of this but as far as this plant grows, even the mountains are covered with esparto grass. Country people there use it for bedding, for fuel and torches, for footwear and for shepherd’s clothes; but it is unwholesome fodder for animals, except the tender growth at the tops. For other purposes it is pulled out of the ground, a laborious task for which gaiters are worn on the legs and the hands are wrapped in woven gauntlets, and levers of bone or holmoak are used; nowadays the work goes on nearly into winter, but it is done most easily between the middle of May and the middle of June, which is the season when the plant ripens.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.7.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.8

VIII. Volsum fascibus in acervo alligatum1 biduo, tertio resolutum spargitur in sole siccaturque et rursus in fascibus redit sub tecta. postea maceratur, aqua marina optume, sed et dulci si marina desit, siccatumque sole iterum rigatur. si repente urgueat desiderium, perfusum calida in solio ac siccatum stans conpendium 29operae patitur.2 hinc3 autem tunditur ut fiat utile, praecipue in aquis marique invictum: in sicco praeferunt e cannabi funes; set spartum alitur etiam demersum, veluti natalium sitim pensans. est quidem eius natura interpolis, rursusque quam libeat 30vetustum novo miscetur. verumtamen conplectatur animo qui volet miraculum aestumare quanto sit in usu omnibus terris navium armamentis, machinis aedificationum aliisque desideriis vitae. ad hos omnes usus quae sufficiant minus x͞x͞x͞ passuum in latitudinem a litore Carthaginis Novae minusque c͞ in longitudinem esse reperientur. longius vehi impendia prohibent.

VIII. When it has been plucked it is tied up in bundles in a heap for two days and on the third day untied and spread out in the sun and dried, and then it is done up in bundles again and put away under cover indoors. Afterwards it is laid to soak, preferably in sea water, but fresh water also will do if sea water is not available; and then it is dried in the sun and again moistened. If need for it suddenly becomes pressing, it is soaked in warm water in a tub and put to dry standing up, thus securing a saving of labour. After that it is pounded to make it serviceable, and it is of unrivalled utility, especially for use in water and in the sea, though on dry land they prefer ropes made of hemp; but esparto is actually nourished by being plunged in water, as if in compensation for the thirstiness of its origin. Its quality is indeed easily repaired, and however old a length of it may be it can be combined again with a new piece. Nevertheless one who wishes to understand the value of this marvellous plant must realize how much it is employed in all countries for the rigging of ships, for mechanical appliances used in building, and for other requirements of life. A sufficient quantity to serve all these purposes will be found to exist in a district on the coast of Cartagena that extends less than 100 miles along the shore and is less than 30 miles wide. The cost of carriage prohibits its being transported any considerable distance.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.8.

Loeb Classical Library

Pliny 19.10

X. Theophrastus auctor est esse bulbi genus circa ripas amnium nascens, cuius inter summum corticem eamque partem qua vescuntur esse laneam naturam ex qua inpilia vestesque quaedam conficiantur; sed neque regionem in qua id fiat nec quicquam diligentius praeterquam eriophoron id appellari in exemplaribus quae equidem invenerim tradit, neque omnino ullam mentionem habet sparti cuncta magna cura persecutus cccxc annis ante nos, ut iam et alio loco diximus, quo apparet post id temporis in usum venisse spartum.

X. Theophrastus states that there is a kind of bulb [Hist. plant., VII. 13. 8, the modern Muscari comosum, etc.] growing in the neighbourhood of river banks, which contains a woolly substance (between the outer skin and the edible part) that is used as a material for making felt slippers and certain articles of dress; but he does not state, at all events in the copies of his work that have come into my hands, either the region in which this manufacture goes on or any particulars in regard to it beyond the fact that the plant is called ‘wool-bearing’; nor does he make any mention at all of esparto grass [It is mentioned in Hist. Plant., I.], although he has given an extremely careful account of all plants at a date 390 years before our time (as we have also said already in another place [XV. 1.]); which shows that esparto grass came into use after that date.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. Pliny 19.10.

Loeb Classical Library

De l’enfance de Pantagruel. Chap. iiii.

Ie trouve par les anciens historiographes et poetes, que plusieurs sont nez en ce monde en façons bien estranges qui seroient trop longues à racompter, lisez le viie livre de Pline si avez loysir

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Pantagruel (athena). Les horribles et espouvantables faictz & prouesses du tresrenommé Pantagruel Roy des Dipsodes, filz du grand geant Gargantua, Composez nouvellement par maistre Alcofrybas Nasier. Lyon: Claude Nourry, 1532. Ch. 4.

Athena

Chap. xxii.: Comment Gargantua employt le temps quand l’air estoit pluvieux.

Mais encores que ycelle iournée feust passée sans livres & lectures, ponct elle n’estoyt passée sans profit. Car en beau pré ilz recoloient par cueur quelques plaisans vers de l’agriculture de Virgile, de Hesiode, du Rustice de Politian, descryvoient quelque plaisans epigrammes en latin: puys les mettoient par rondeaux & balades en langue françoise, En bancquetant du vin aisgué separoient l’eau, comme l’enseigne Cato de re rust. & Pline, avecques un goubelet de Lyerre, lavoient le vin en plain bassin d’eau puys le retiroient avec un embut faisoient aller l’eau d’un verre en aultre, bastissoient plusieurs petitz engins automates, c’est à dyre, soy movens eulx mesmes.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Gargantua. La Vie Inestimable du Grand Gargantua, Pere de Pantagruel, iadis composée par l’abstracteur de quinte essence. 1534. Ch. 22.

Athena

Chap. xxi. Comment Gargantua feut institué par Ponocrates en telle discipline, qu’il ne perdoit heure du iour.

Au commencement du repas estoyt leur quelque histoire plaisante des anciennes prouesses: iusques à ce qu’il eut print son vin. Lors (sy bon sembloyt) on continuoyt la lecture: ou commenceoient à diviser ioyeusement ensemble, parlans pour les premiers moys de la vertus, proprieté/ efficace/ & nature, de tous ce que leur estoyt servy à table. Du pain/ du vin/ de l’eau/ du sel/ des viandes/ poissons/ fruictz/ herbes/ racines/ et de l’aprest d’ycelles. Ce que faisant aprint en peu de temps tous les passaiges à ce competens en Pline, Atheneus, Dioscorides, Galen, Porphyrius, Opianus, Polybieus, Heliodorus, Aristotele, Aelianus, & aultres. Iceulx propos tenens faisoient souvent, pour plus estre asseurez, apporter les livres sudictz à table. Et si bien & entierement retint en sa memoire les choses dictes, que pour lors n’estoit medicin, qui en sceust à la moytié tant comme ilz faifaisoient.

…

Le temps ainsi employé luy frotté, nettoyé, & refraischy d’habillemens, tout doulcement s’en retournoyt & passans apr quelques prez, ou aultres lieux herbuz visitoient les arbres & plantes, les conferens avec les livres des anciens qui en ont escript comme Theophraste, Dioscorides, Marinus, Pline, Nicander, Macer, & Galen. Et en emportoient leurs plenes mains au logis, desquelles avoyt la charge un ieune page nommé Rhizotome, ensemble des marrrochons, des pioches, cerfouetes, beches, tranches, & aultres instrumens requis à bien arborizer.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Gargantua. La Vie Inestimable du Grand Gargantua, Pere de Pantagruel, iadis composée par l’abstracteur de quinte essence. 1534. Ch. 21.

Athena

Pantagruel refers to Plutarch, Pliny

Comment Pantagruel conseille Panurge prevoir l’heur ou le malheur de son mariage par songes.

Chapitre XIII.

Or puys que ne convenons ensemble en l’exposition des sors Virgilianes, prenons aultre voye de divination. Quelle? (demanda Panurge), Bonne, (respondit Pantagruel) antique, & authenticque, c’est par songes. Car en songeant avecques conditions les quelles descripvent Hippocrates lib., Platon, Plotin, Iamblicque, Synesius, Aristoteles, Xenophon, Galen, Plutarche, Artemidorus Daldianus, Herophilus, Q. Calaber, Theocrite, Pline, Atheneus, et aultres, l’ame souvent prevoit les choses futures.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Le Tiers Livre des Faicts et Dicts Heroïques du bon Pantagruel: Composé par M. Fran. Rabelais docteur en Medicine. Reueu, & corrigé par l’Autheur, ſus la cenſure antique. L’Avthevr svsdict ſupplie les Lecteurs beneuoles, ſoy reſeruer a rire au ſoixante & dixhuytieſme Liure. Paris: Michel Fezandat, 1552. Ch. 13.

Les Bibliotèques Virtuelles Humanistes

Rabelais and Pliny

i

Pendant que ses compagnons à robe grise faisaient leurs délices d’une messe bien chantée, d’une matine rondement sonnée, d’une quête fructueusement prêchée, le jeune frère mineur ne s’attachait que modérément à cete partie essentielle de la règle de saint François, son patron. Il a’y attacha si peu, il remplaça si souvent la lecture de la Bible par celle de Plaute, on lui vit si souvent en main les auteurs profanes de la Grèce et de Rome au lieu des pieuses élucubrations de Scot, qu’il devint odieux à la communauté. Une perquisition faite dans sa cellule ayant amené la découvert de livres épouvantables — il s’y trouvait l’Histoire naturelle de Pline et quelques écrits d’Erasme — Rabelais dut prendre la fruite et se cacher dans une maison amie.

iii

«Ainsi, dit Colletet, par la force de son esprit et pas ses longs travaux, il s’aquit cette polymathie que peu d’hommes ont possédée, car il est certain qu’il fut très-savant humaniste et très-profond philosophe, thélogien, mathématicien, medicin, juriscontulte, musicien, géomètre, astronome, voire même peintre et poëte tout ensemble. Mais comme la science des choses naturelles était celle qui revenait le plus à son humeur, il résolut de s’y appliquer entièrement et, à cet effet, il s’en alla droit à Montpellier.»

Eugène Noël raconte en ces termes l’arrivée de Rabelais à Montpellier:

«Il avait suivi la foule dans un salle où avait lieu une discussion sur la botanique, … sa réputation l’avait devancé à l’école, personne n’ignorait son prodigieux savoir, … alors il parle des plantes avec tant de charme, d’éloquence et de clarté, et présente la plupart des questions sous un aspect si nouveau, que les applaudissements éclatent de toutes les parties de la salle et que l’auditoire en masse, docteurs, élèves et public, accompagne maître François jusqu’au lieu de sa demere.»

v

Il expliqua, devant un nombreux auditoire, les aphorismes d’Hippocrate et l’art médical de Galien.

xii

Brémond, Félix,

Rabelais Médecin. Avec notes et commentaires. Gargantua. Paris: Mme V. Pairault, 1879. i.

Google Books

TL Ch. 13

CHAPTER XIII

How Pantagruel adviseth Panurge to try the future good or bad Luck of his Marriage by Dreams

” Now seeing that we do not agree together in the Interpretation of the Virgilian Lots, let us try another Way of Divination.”

” Which Way ? ” asked Panurge.

Pantagruel answered : ” A Way good, ancient and authentic. It is by Dreams ; for in dreaming with the Conditions described by

Hippocrates, lib. [greek]

Plato,

Plotinus,

lamblichus,

Synesius,

Aristotle,

Xenophon,

Galen,

Plutarch,

Artemidorus Daldianus,

Herophilus,

Q. Calaber,

Theocritus,

Pliny,

Athenaeus

and others, the Soul doth oftentimes foresee what is to come.

“There is no need to prove it to you more at length; you may understand it by a common Instance ; as, when you see that Children, clean washed, well fed and suckled, are sleeping soundly, their Nurses go off to disport themselves at Liberty, as being for that time licensed to do what they will, for their Presence about the Cradle would be thought unnecessary.

“Even so our Soul, when the Body sleeps and the Digestion is in all Parts completed, nothing being necessary till the Waking up, takes its Pastime and revisits its native Country, which is Heaven.

” From there it receiveth a notable Participation of its first divine Origin, and in Contemplation of that infinite and intellectual Sphere, the Centre of which is in every Place in the Universe and the Circumference nowhere, that is to say, God 4 (according to the Doctrine of Hermes Trismegistus), to whom no New thing happeneth, whom nothing escapeth, from whom nothing falls away, to whom all Time is present, notes not only what has passed in Things moving here below, but also Things to come, and by reporting them to the Body, and then, by means of the Body’s Senses and Organs, setting them forth to its Friends, that Soul is termed Vaticinating and Prophetic.…”

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 2: Books IV-V and minor writings. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893. p. 435

. Internet Archive

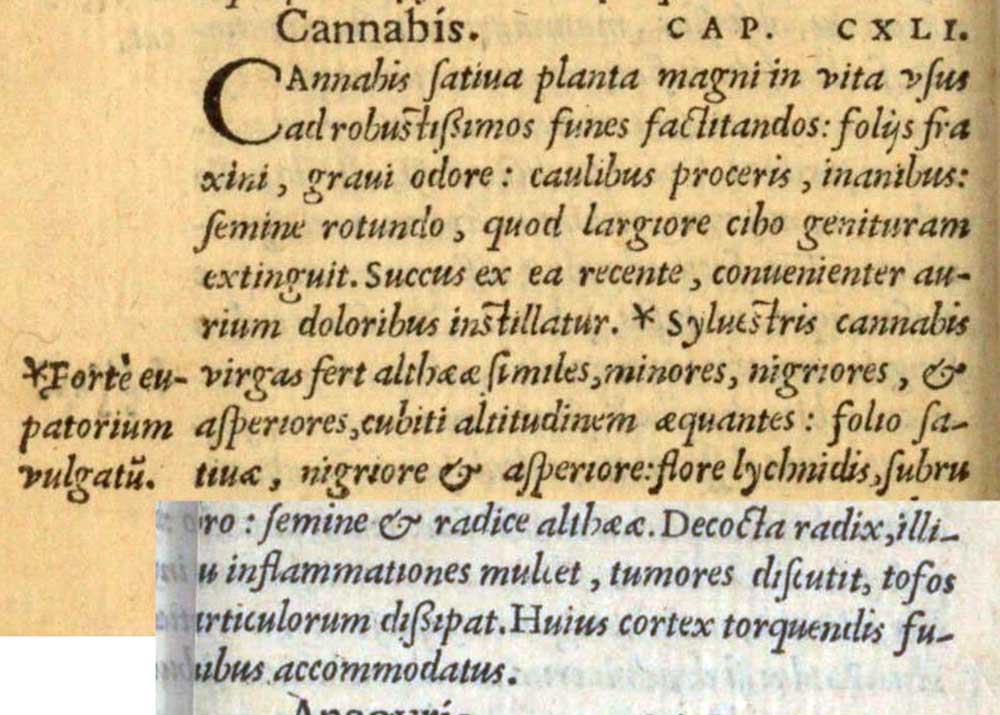

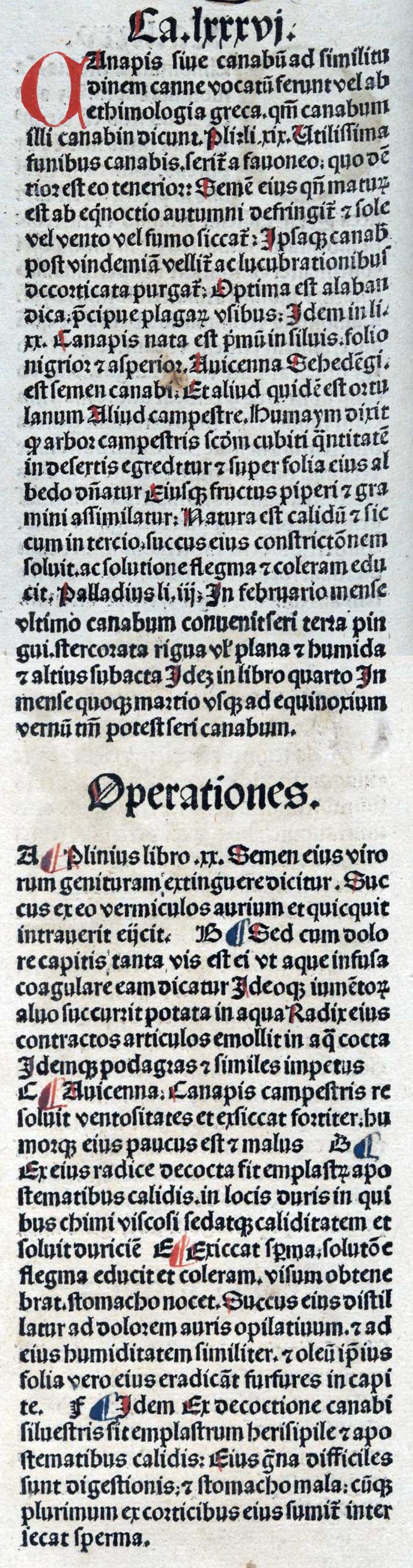

Pantagruelion

C’est le chanvre (Cannabis sativa L.) que Rabelais va décrir sous le nom de Pantagruelion. L’idée et le plan même de cette description du chanvre lui ont été suggérés par celle que Pline a donnée du lin au début du l. XIX de son Hist nat. V. Plattard, L’Œuvre de R., p. 154-164. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 339.

Internet Archive

Pliny

Pliny the Elder (born Gaius Plinius Secundus, AD 23 – 79) was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, as well as a naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire. Spending most of his spare time studying, writing, and investigating natural and geographic phenomena in the field, Pliny wrote the encyclopedic Naturalis Historia (Natural History).