QV

Notes

Des Fileurs. Les filamens de chanvre qui forment le premier brin, n’ont que deux ou trois piés de longueur ; ainsi pour faire une corde fort longue, il faut placer un grand nombre de ces filamens les uns au bout des autres, & les assembler de maniere qu’ils rompent plûtôt que de se desunir, c’est la propriété principale de la corde ; & qu’ils résistent le plus qu’il est possible à la rupture, c’est la propriété distinctive d’une corde bien faite. Pour assembler les filamens, on les tord les uns sur les autres, de maniere que l’extrémité d’une portion non assemblée excede toûjours un peu l’extrémité de la portion déjà tortillée. Si l’on se proposoit de faire ainsi une grosse corde, on voit qu’il seroit difficile de la filer également, (car cette maniere d’assembler les filamens s’appelle filer), & que rien n’empêcheroit la matiere filée de cette façon, de se détortiller en grande partie ; c’est pourquoi on fait les grosses cordes de petits cordons de chanvre tortillés les uns avec les autres ; & l’on prépare ces cordons, qu’on appelle fil de carret, en assemblant les filamens de chanvre, comme nous venons de l’insinuer plus haut, & comme nous allons ci-après l’expliquer plus en détail.

[See the reference for an encyclopedic treatment of ropemaking.]

These illustrations of the preparation of hemp are from Volume 18 of the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de Gens de lettres, published under the direction of Denis Diderot (1713–1784) and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (1717–1783) in 17 volumes of text and 11 volumes of plates between 1751 and 1772.

Online version available from the ARTFL Project (American and French Research on the Treasury of the French Language). Illustrations and text displayed here are from this service.

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc., eds. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert. University of Chicago: ARTFL Encyclopédie Project (Autumn 2017 Edition), Robert Morrissey and Glenn Roe (eds)

AGRICULTURE ET ECONOMIE RUSTIQUE

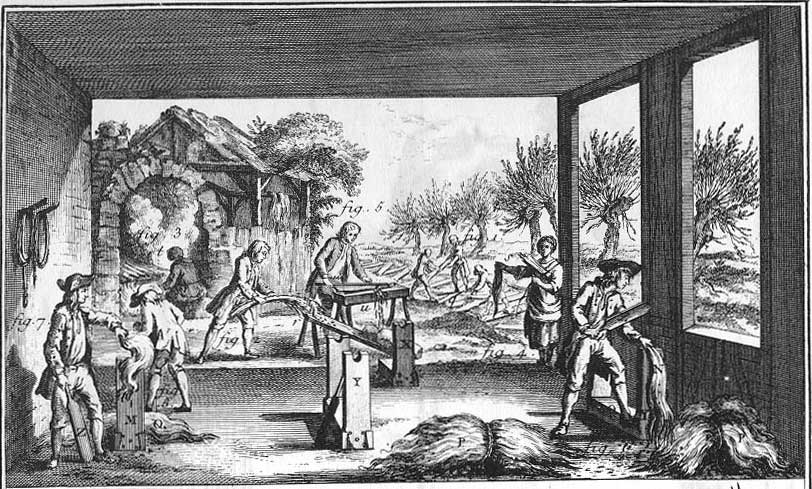

CHANVRE, Premier travail à la campagne.

PLANCHE Iere.

Premiere & seconde divisions. Travail du chanvre.

PLANCHE Iere. Premiere division. Travail du chanvre.

La vignette représente l’attelier des espadeurs, dont le mur du fond est supposé abattu pour laisser voir dans le lointain les préparations premieres & champêtres du chanvre. Quand il a été arraché de terre, & qu’on a séparé le mâle d’avec la femelle, on le fait sécher au soleil ; ensuite on le frappe contre un arbre ou contre un mur, pour en détacher les feuilles ou le fruit, & on le fait roüir ou dans une mare ou dans un ruisseau, ou enfin dans ce qu’on appelle un routoir ; c’est un fosse où il y a de l’eau.

Fig. 1. Routoir q, où l’on a mis le chanvre. Plusieurs hommes sont occupés à le couvrir de planches, & à les charger de pierres pour le tenir au fond de l’eau, & l’empêcher de surnager.

Fig. 2. Ouvrier qui passe le chanvre sur l’égrugeoir r, pour détacher le grain qui y est resté.

[page 18:1:9]

Fig. 3. Le haloir t. C’est une espece de cabane où l’on fait sécher le CHANVRE. en le posant sur des bâtons au-dessus d’un feu de chenevote.

Fig. 4. Une femme s qui tille du CHANVRE. c’est-à-dire qui en rompant le brin, sépare l’écorce du bois.

Fig. 5. Ouvrier qui rompt la chenevote entre les deux mâchoires de la broye u.

Fig. 6. Ouvrier qui espade, c’est-à-dire qui frappe avec l’espadon Z sur la poignée de chanvre N qu’il tient dans l’entaille demi-circulaire de la planche verticale du chevalet Y.

Fig. 7. Ouvrier qui, pour faire tomber les chenevotes, secoue contre la planche M du chevalet la poignée de chanvre qu’il a espadée.

Fig. 8. Autre espadeur qui fait la même opération sur l’autre planche verticale du chevalet.

Fig. 9. Bas de la planche. L’égrugeoir dont se sert l’ouvrier de la figure 2. L’extrêmité de cet instrument qui pose à terre, est chargée de pierres pour l’empêcher de se renverser.

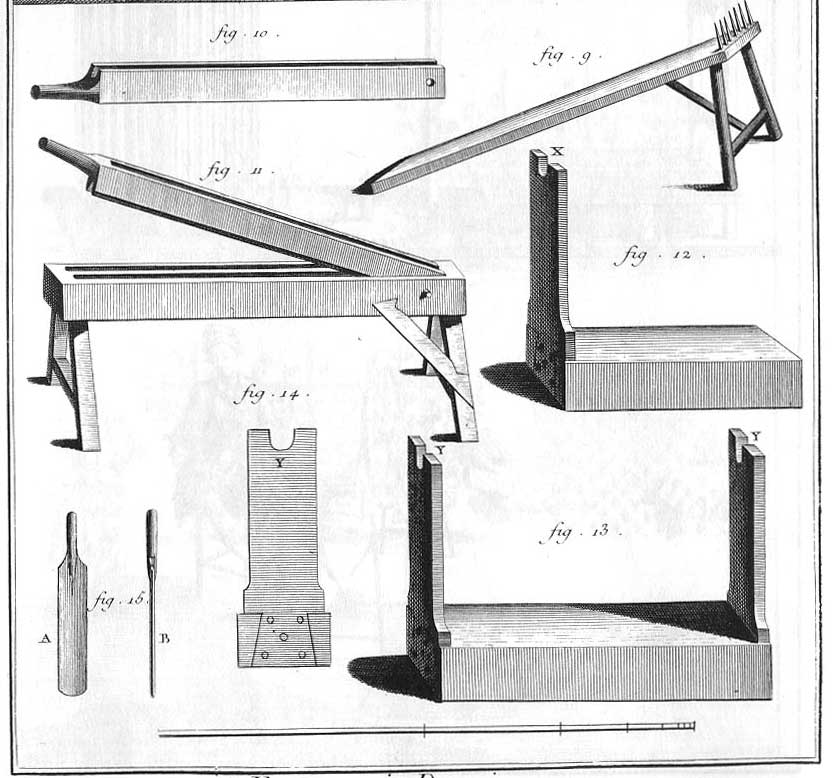

PLANCHE Iere. Seconde division. Travail du chanvre.

Fig. 10. Mâchoire supérieure de la broye vûe par dessous. On voit qu’elle est fendue dans toute sa longueur pour recevoir la languette du milieu de la mâchoire inférieure, & former avec celle-ci deux languettes ou tranchans mousses propres à rompre & briser la chenevote.

Fig. 11. La broye toute montée. La mâchoire supérieure est retenue dans l’inférieure par une cheville qui traverse tous les tranchans.

Fig. 12. Chevalet simple, X, le même que celui cotté X dans la vignette.

Fig. 13. Chevalet double, Y Y , le même que ceux cottés M, Y, dans la vignette.

Fig. 14. Elévation d’une des planches du chevalet, soit simple, soit double.

Fig. 15. Elévation & profil d’un espadon vû de face en A, & de côté en B.

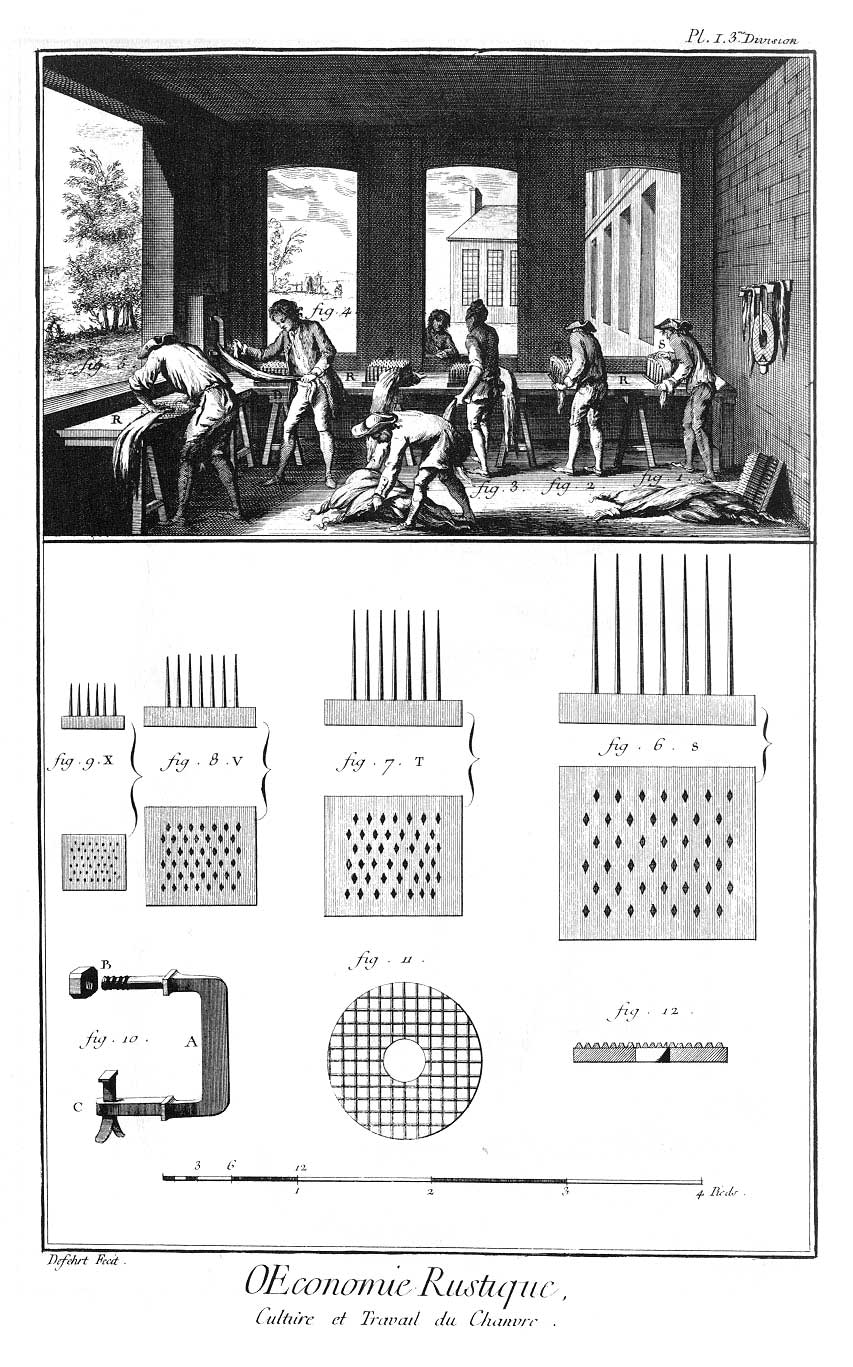

PLANCHE Iere. Troisieme division servant de Planche seconde. La vignette représente l’attelier des peigneurs.

La vignette représente l’attelier des peigneurs.

Fig. 1. 2. 3. Peigneurs dont les uns peignent le chanvre sur le peigne à dégrossir, & d’autresa sur les peignes à affiner. Ces peignes sont posés sur de grandes tables R portées sur des treteaux & scellées dans le mur.

Fig. 4. Peigneur qui passe sa poignée de chanvre dans le fer A, pour en affiner le milieu, & faire tomber les chenevottes que le peigne n’a pas ôtées.

Fig. 5. Ouvrier qui frotte le milieu de sa poignée sur le frottoir, pour achever d’affiner cette partie.

Bas de la Planche.

Fig. 6. S, plan & élévation d’un grand peigne ou seran garni de quarante-deux dents de douze à treize pouces de longueur. Il sert à former les peignons.

Fig. 7. T, peigne à dégrossir, garni du même nombre de dents de sept à huit pouces de longueur.

Fig. 8. V, plan & élévation du peigne à affiner. Les dents en même nombre ont quatre ou cinq pouces.

Fig. 9. Plan & élévation d’un peigne fin dont les dents sont au nombre de trente-six.

Fig. 10. Fer séparé du poteau auquel il est attaché dans la vignette. La branche coudée qui traverse le poteau en B étant terminée en vis, est reçûe dans un écrou. C, représente une autre maniere de le fixer : c’est une clavette double qui traverse la branche coudée, & l’empêche de sortir.

Fig. 11. & 12. Plan & coupe du frottoir.

In Plato’s Cratylus, Socrates was asked whether names were conventional or natural.

Cette question qui porte sur la valuer de sens, est étroitement liée à celle de son origine, dont le dévoilment apporterait sans doubte les clartés ou les garanties nécessaires pour juger de sa vérité. Savoir d’où viennent les mots, ne serait-ce pas savoir d’où viennent leurs sens, qui en a décidé, quel «législateur» plus ou moins bien inspiré ? Cette question d’étiologie inclut cependant bien plus que la seule étymologie (Dieu sait que Rabelais en use, et du calembour, qui est forme d’étymologie burlesque) : elle oblige à porter l’investigation jusqu’en ces lieux, jusque’à ces institutions, où, avec ceux qui les représentent, les significations sont fabriquées, arrêtées, débatues, divulguées, imposées.

[De Hanff-Cannabus] Hemp is warm, and when the air is neither very warm nor very cold, it grows and so too is its nature, and its seeds contain healing power, and it is wholesome for healthy people to eat, and in their stomachs it is light and useful, so that it carries out the mucus from the stomach to some extent,and it can be easily digested, and it diminishes the bad humors and makes the good humors strong. But he who is ill in the head and has an empty brain and eats hemp, this will easily cause him some painin the head. But he who has a healthy head and a full brain in the head, it will not harm him. But he who has a cold stomach, he should boil hemp in water and, after pressing out the water, wrap it in a small cloth. And he should lay it upon his stomach often while thus warm, and this will strengthen him and bring him back to his condition.

[Quoted in Christian Rätsch, Marijuana Medicine. A World Tour of the Healing and Visionary Powers of Cannabis. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press, 2001, p. 108. Google Books

Original Latin

Montague Summers translation. A tedious and misogynist tract.

The missing study referred to by Abel 1980.

Referred to in “Micromorphology”:

In a previous study, using a light microscope, we observed how, in addition to the capitate glandular hairs, there were other hairs – sessile hairs or hairs with very short stalks – present on the bract covering the female flower –

Institute of Pharmacology and Pharmacognosy, University Messine, Italy

The electron scanning microscope is of great use in pharmacognosy because it enables valuable contributions to be made to the study of the micromorphology of the superficial tissues of drugs.

1. A. De Pasquale (1970 a). “Farmacognosia della Canape indiana. II. Ricerche morfologiche”. Lavori Istituto Farmacognosia Università Messina , 6: 9.

A. De Pasquale (1970 b). “Prime osservazioni al microscopio ellettronico sulla Canape indiana”. Lavori Istituto Farmacognosia Università Messina , 6: 1.

Invariably, whenever medieval artists turned to the subject of the Witches’ Sabbath, they depicted a group of women, who were usually naked, compounding a mysterious drug in a large cauldron. As early as the fifteenth century, demonologists declared that one of the main constituents that the witches compounded for their heinous ceremony was hemp.

In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued a papal fiat condemning witchcraft and the use of hemp in the Satanic mass. [4] In 1615, an Italian physician and demonologist, Giovanni De Ninault, listed hemp as the main ingredient in the ointments and unguents used by the devil’s followers. [5] Hemp, along with opium, belladonna, henbane, and hemlock, the demonologists believed, were commonly resorted to during the Witches’ Sabbath to produce the hunger, ecstasy, intoxication, and aphrodisia responsible for the glutinous banquets, the frenzied dancing, and the orgies that characterized the celebration of the Black Mass. Hemp seed oil was also an ingredient in the ointments witches allegedly used to enable them to fly. [6]

Jean Wier, the celebrated demonologist of the sixteenth century, was quite familiar with the exhilarating effects of hemp for sinister purposes. Hemp, he wrote, caused a loss of speech, uncontrollable laughter, and marvelous visions. Quoting Galen, he explained that it was capable of producing these effects by “virtue of affecting the brain since if one takes a large enough amount the vapors destroy the reason.” [7]

4. A. De Pasquale, “Farmacognosia della ‘Canape Indiana'”, Estratto dai Lavori dell’Instituto di Farmacognosia dell’Universita di Messina 5 (1967): 24.

5. Ibid. Cf. also, Cornelius Agrippa, De Oculta Philosphia (n.d.), vol 43; and Pierre d’Alban, Heptameron seu Elementa Magica (1567), p. 142.

6. P. Kemp, The Healing Ritual, (London: Faber and Faber, 1935), pp. 57, 198.

7. Quoted in De Pasquale, “Farmacognosia”, p. 24.

In the next century, the French writer and physician François Rabelas wrote at length about cannabis, calling it Pantagruelion. Pantagruelion, says Rabelais, “is sown at the first coming of the swallows, and is taken out of the ground when the grasshoppers begin to get hoarse.” Its stalk is “full of fibers, in which consist the whole value of the herb” (italics mine). Following Pliny, he declares that the seeds produced by the male plant “destroy the procreative germs in whosoever should eat much of it or often.” Referring to Galen, he says, “still it is of difficult concotion, offends the stomach, engenders bad blood, and by its excessive heat acts upon the brain and fills the head with noxious and painful vapors.”

If Rabelais knew anything about the effects of cannabis, he did not record them. Proably he did not. Beyond what he recorded from these classical sources, it is unlikely the Rabelais was in any way familiar with cannabis as a medicament or as a psychoactive agent.

In Switzerland, the hemp fields in the allmend (the collective fields of a community) were once the site for various pagan and erotic rituals that the authorities interpreted as “witches’ dances” or the “witches’ sabbath.”

Quoted in Rätsch, Christian, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants. Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications. Simon and Schuster, 2005. Google Books

Throughout history, the plant’s psychoactive properties have consistently been incorporated into the rites of mystical religions throughout history. In Ancient Western Societies, the Mystery Religions of the Great Mother Goddess utilized hemp in their sacred rites. The use of the hemp’s psychoactive properties persisted in the West as a feature of pagan religions and medicines until the Inquisitions of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries formally outlawed the use of cannabis for religious and medicinal purposes. A few centuries later, Catholic dogma was firmly established by Pope Innocent VIII, when in 1484, he issued a precedent setting bull which clearly labeled the users of cannabis as heretics and worshippers of Satan.Despite persecution against the religious and medicinal use of the drug, hemp remained an agricultural staple in the West, where it was highly valued as a source of fiber and seed. [n. 25] Ironically, after it was formally outlawed by the Pope in 1484, hemp took on a new historical importance.

[25]

Ernest L. Abel, Marihuana: The First Twelve Thousand Years (New York: Plenum Press, 1980), p. 61-109

The Dominican monks Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger assembled many fairy tales and magic stories, nightmares, hearsay, confessions and accusations and put this all together as factual information in what became the handbook for the witch hunters, examiners, torturers and executioners, called the Malleus Maleficarum, a title which was translated as Hammer of Witches. It was published in 1487, but two years previously the authors had secured a bull from Pope Innocent VIII, authorizing them to continue the witch hunt in the Alps which they had already instituted against the opposition from clergy and secular authorities. They reprinted the bull of December 5, 1484, to make it appear that the whole book enjoyed papal sanction.

A Bull of Innocent VIII said by many to specifically prohibit hemp.

It has been necessarily thus briefly to review this important series of Papal documents to show that the famous Bull Summis desiderantes affectibus, 9 December, 1484, which Innocent VIII addressed to the authors of the Malleus Maleficarum.

Search of a latin transcription for cannabis or kannabis yields no results.

Search of the transcription of Montague Summer’s translation for hemp or cannabis, the only reference to hemp is a note to Part Iii, Second Head, Question Xiii.

And some also are distinguished by the fact that, after they have admitted their crimes,they try to commit suicide by strangling or hanging themselves

Note by Sommers: “There are recorded many instances of this,” including “John Stewart, a warlock of Irvine, in 1618 “who after confessing, “was fund by the burrow officers, quha went about him stranglit and hangit be the cruik of the dur, with ane tait of hemp (or a string maid of hemp, supposed to haif been his garters, or string of his bonnet) not above the length of two span long.”

“Cannabis” is not found in the transcription of the English translation.

During Europe’s dark ages, pagan herbalists and witches, mostly women, used cannabis in their ointments and cures. During a time when illness was equated with evil, these pagans attracted a devout following for their miraculous healing lore. The Catholic Church, threatened by the resurgence of ancient religions and by forms of medicine that challenged their exclusive right to perform healings, gruesomely tortured these women to extract confessions of supposedly satanic allegiance, and then burned them to death in public forums.

Around 1000 AD, in festivals celebrating the love goddess Ostara, Easter bunnies were killed and consumed during orgiastic pagan festivals that involved cannabis. Such are the findings of Dr Christian Rätsch, after studying libraries of ancient German texts. “[Ostara’s] sacred animals, the hares, would be sacrificed and eaten in a communal meal?” he wrote in his book, Marijuana Medicine. “It [was]best washed down with a good hemp beer. Unfortunately, the Bacchanalian orgies that followed fell victim to the Christian Liturgy.”

[…]

In fact, cannabis was a common feature of pagan fertility celebrations in the first 1000 years AD. Like Ostara, the love goddesses Freya and Venus were also often worshipped with cannabis offerings. Cannabis was one of the many psychedelic ingredients in the legendary flying ointment of medieval witches, which was known to induce visions. The ingredients were heated in oil, which was then applied to a broomstick and inserted into the vagina during a masturbatory ritual. (note 1) Gallic druids (Holy men of the Gauls) also used cannabis to get high.

Pagan healers, mostly wise women, used cannabis for a number of medicinal benefits. Curiously, some of the earliest evidence of medical-cannabis using pagans comes from the writings of famous Catholic nun and herbalist Hildegard von Bingen of Germany (1098-1179). Hildegard’s self-education included ancient Greek medicine and local pagan folk remedies. From her education with pagan wise women, she learned of cannabis’ healing powers. In her famous work Physia, in an entry titled “Of Hemp”, she writes that “hemp is warm? it is wholesome for healthy people to eat? it can be easily digested, and it diminishes the bad humours and makes the good humours strong.” Curiously, Hildegard also wrote poetry to the “Green Power,” and had strong visions, similar to Joan of Arc, who was accused of using the psychedelic mandrake plant and then burned as a witch. Hildegard von Bingen’s unprecedented influence on the early German pharmacopoeia ensured that cannabis remedies would eventually become common across Europe.

…the herbal painkiller Unguentum Populeum became increasingly popular while the excruciating Black Death ravaged Europe. In 1991, German researcher Herman de Vries revealed that later recipes for this ointment contained cannabis, a potent analgesic for the internal pains caused by the plague. (note 2)

Curiously, as Christian Rätsch notes, the recipe for Unguentum Populeum was exactly the same as that for the flying ointment. The similarity between the flying ointment and the painkiller leads to the conclusion that pagan women were the original source of the popular medicine.

[…]

In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII suddenly changed his mind about witches. Until that date, his official position was that they didn’t exist. Now, because of a lengthy papal bull called the Malleus Mallificarum, not only did witches exist, but they were to be persecuted, tortured and killed. Pope Innocent VIII made it well known that witches included midwives and herbalists.

According to Ernest Able, a former scholar of medieval studies at the University of Toronto and author of Marijuana: The First 12,000 Years, Pope Innocent VIII also specifically condemned cannabis in 1484, called the herb “an unholy sacrament” of satanic masses, and banned its use as a medicine. Too bad the pope didn’t have the good sense to burn cannabis in a bowl instead of witches at the stake.

That same year the pope also banned literature, like George Gifford’s, that made fun of the church, saying such works were “a mass of the travesty.” In The Emperor Wears No Clothes, Jack Herer speculates that these prohibitions were also intended to stop people who were high on cannabis from laughing uncontrollably at the ridiculous excesses of the church.

[…]

Demonologists who sprang up in abundance to combat the sudden scourge of witches after 1484 often found cannabis and other psychedelics in the pantries of those they branded “witches.”

In 1615, the Italian physician Giovanni De Ninault, who persecuted witches in his spare time, listed cannabis, belladonna, henbane and hemlock as common ingredients in what was known as “flying ointment” when inserted in the vaginas of witches, and as Unguentum Populeum when used to treat painful maladies. According to De Ninault, these ingredients were carried in hemp seed oil, which would have been an excellent solvent for their mind-expanding and pain-killing alkaloids.

The psychedelic plants mandrake, datura and monkshood were also likely ingredients in the flying ointment and in the medicinal Unguentum Populeum. In fact, just about any psychedelic plant or fungus that might be found in Europe at that time is likely to have been used by herbal loremasters in their brews and ointments.

[…]

What pagan-haters called “orgies with the devil” were actually fertility rites to the love goddesses of the various pagan sects across Europe, at which cannabis was used as an aphrodisiac to inspire communal lovemaking. In an interview with Cannabis Culture, entheobotanist Christian Rätsch spoke about the cannabis prohibitions against sexuality embodied by Ostara worship, in which pagans quaffed barrels of psychoactive beer.

“The old Germans were really fond of their beer,” said Rätsch. “But it was brewed by women and these women used all kinds of herbs in the brewing process including hemp and henbane, and these beers were always related to pagan ritual and to fertility and of course to sex an so on. And this whole thing was suppressed by the Catholic Church in the time of the witch hunts, and the Germans passed out a law against brewing beer with any other herbs but hops.”

“There were also some cases from Switzerland in the records of the Inquisition, when locals harvested the cannabis fields. Young women got very high on cannabis fumes and they started to dance naked in the cannabis field to be observed by boys, who were old enough to marry. In the 17th Century, the church called these erotic harvest rituals ‘witches’ sabbaths’ and tried to suppress them.”

In his 1996 book Verboten Lust, Kurt Lussi describes how young female devotees of the Norse love goddess, Freya, would steal away to the cannabis fields at night to make a wreath of hemp, which they would throw onto a tree bough, while being watched by local boys an early pagan form of innocent courtship that was captured in the records of the Inquisition as a satanic ritual.

In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII suddenly changed his mind about witches. Until that date, his official position was that they didn’t exist. Now, because of a lengthy papal bull called the Malleus Mallificarum, not only did witches exist, but they were to be persecuted, tortured and killed. Pope Innocent VIII made it well known that witches included midwives and herbalists.

According to Ernest Able [sic], a former scholar of medieval studies at the University of Toronto and author of Marijuana: The First 12,000 Years, Pope Innocent VIII also specifically condemned cannabis in 1484, called the herb “an unholy sacrament” of satanic masses, and banned its use as a medicine.

In 1231, Pope Gregory IX initiated the Holy Inquisition, its aim to root out and destroy the heresies of the previous two centuries. Hemp, being regarded as sorcerous, was outlawed as heretical. Those who used it, whether for medical purposes or divination, were branded as witches who, in turn, were considered heretics. The persecution of witches across Europe commenced in earnest in 1484, with the publication of a papal bull issued by Pope Innocent VIII entitled Summis Desiderantes.

[no sources cited]

In January 1997, a Pope-approved statement issued by the Pontifical Council for the Family claimed that legalizing drugs would be akin to legalizing murder, and also called for the banning of tobacco.

These statements are consistent with the Catholic Church’s longstanding policy of official hatred for marijuana and other medicinal and psychoactive herbs. Catholic Popes have been viciously persecuting users of medicinal plants virtually since the formation of the Church.

For much of Europe’s history, the Roman Catholic Church was fighting wars of destruction against many “heretical” sects. In many cases, these so-called heretics had rediscovered the herbal sacraments like mushrooms and cannabis, and were ruthlessly exterminated for their use of these powerful plants.

[…]

The Pope who launched the most vicious of the Catholic Church’s many campaigns against herb users was Pope Innocent VIII (1432-1492). In 1484 he issued a papal bull called “Summis desiderantes” which demanded severe punishments for magic and witchcraft, which at the time usually meant the use of medicinal and hallucinogenic herbs. Indeed, the papal bull specifically condemned the use of cannabis in worship instead of wine.

The principles Pope Innocent VIII outlined became the basis for the terrifying and torturous witch-hunters’ handbook, the Malleus Maleficarum (1487).

Further, Pope Innocent VIII was a major supporter of the vicious Inquisition, and in 1487 he appointed the infamous and sadistic Spanish friar Torquemada as Grand Inquisitor. Under Torquemada’s authority, thousands of traditional female healers, users of forbidden plants, Jews, and other “heretics” were viciously tortured and killed during the “witch-hunts” of the Spanish Inquisition. This reign of terror gripped Europe well into the 17th Century.

[…]

Clearly, not all Catholics have supported their Church’s war on cannabis. During the middle ages, the most famous Catholic voice in support of marijuana was a French monk and author named Rabelais (1495-1553).

Although Rabelais’ classic books Gargantua and Pantagruel superficially appear to be merely a bawdy tale about a noble giant and his son, a deeper reading reveals a telling parody of Church and State, and contains many detailed and positive references to cannabis, which Rabelais dubbed “The Herb Pantagreulion” to avoid persecution.

Yet Rabelais still suffered for his written work in support of marijuana. He was harassed and persecuted by the Church, and the chapters that most specifically refer to marijuana (Book 3, chap 49-52) were banned by the Catholic Church. The power of this censorship has lasted for centuries, as even in many modern translations of Pantagruel these chapters are omitted.

The Malleus Maleficarum,[2] usually translated as the ,[3][a] is the best known and the most thorough treatise on witchcraft.[6][7] It was written by the discredited Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name Henricus Institoris) and first published in the German city of Speyer in 1487.[8] It endorses extermination of witches and for this purpose develops a detailed legal and theological theory.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15] It was a bestseller, second only to the Bible in terms of sales for almost 200 years.[16] It has been described as the compendium of literature in demonology of the fifteenth century.[17] The top theologians of the Inquisition at the Faculty of Cologne condemned the book as recommending unethical and illegal procedures, as well as being inconsistent with Catholic doctrines of demonology.[18]

The Malleus elevates sorcery to the criminal status of heresy and prescribes inquisitorial practices for secular courts in order to extirpate witches. The recommended procedures include torture to effectively obtain confessions and the death penalty as the only sure remedy against the evils of witchcraft.[19][20] At that time, it was typical to burn heretics alive at the stake[21] and the Malleus encouraged the same treatment of witches. The book had a strong influence on culture for several centuries.[b]

Jacob Sprenger’s name was added as an author beginning in 1519, 33 years after the book’s first publication and 24 years after Sprenger’s death;[25] but the veracity of this late addition has been questioned by many historians for various reasons.[26][25]

Kramer wrote the Malleus following his expulsion from Innsbruck by the local bishop, due to charges of illegal behavior against Kramer himself, and because of Kramer’s obsession with the sexual habits of one of the accused, Helena Scheuberin, which led the other tribunal members to suspend the trial.[27]

It was later used by royal courts during the Renaissance, and contributed to the increasingly brutal prosecution of witchcraft during the 16th and 17th centuries.

In 1861, T. Hughes suggested publishing a notice in Notes and Queries concerning Randle Cotgrave,(1) compiler of the first complete French-English dictionary in 1611; the notice never appeared. Other attempts were made to identify Cotgrave, sometimes supposing that Hugh Cotgrave (a Herald who died in 1584) was his father.(2) Cotgrave’s entry in The Dictionary of National Biography is inaccurate and unhelpful and this note aims properly to identify Cotgrave and give brief details of his life.(3)

Randle Cotgrave was born in about 1569, the son of Randolph Cotgrave (1541-92), the registrar of the diocese of Chester.(4) Father and son both attended the King’s School in Chester, which the younger left in about 1586 before going to St John’s College, Cambridge; he was later admitted to the Inner Temple.(6) At Cambridge, Randle Cotgrave met William Cecil, son of the Earl of Exeter and went on to work as Cecil’s secretary. He was also involved in Cecil’s business, being a party to several indentures.(7) Cotgrave dedicated his Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues to Cecil, since the time it had taken to prepare “might have beene otherwise imploded” in his master’s service. Cecil already spoke French, so Cotgrave admitted that the work could not have been “a Worke of lesse use for our Lordship”. “Rowland Cotgrave” presented Prince Henry with a copy of the dictionary in 1611, for which he received a gift of 10[pounds].(8)

[…]

Randle Cotgrave lived in the parish of St Bartholomew the Great in London, where his son was buried in 1619 and his wife in 1638.(12) Cotgrave himself was buried at St James, Clerkenwell, on 21 March 1652-3.(13) Other Cotgraves mentioned in this parish may have been his offspring; Helen Cotgrave (died 1622) may have been named after Randle’s mother, Helen Taylor.(14)

(1) N&Q 2nd series, xii, 39.

(2) P. Cotgreave, `A Note on Hugh Cotgrave’, The Coat of Arms, in the press. J. Brownbill, `The Cotgrave Family’, The Cheshire Sheaf, 3rd Series, iv, 39. N&Q 2nd Series, x, 9.

(3) Other information about Cotgrave will be found in M. Eccles, `Randle Cotgrave’, Studies in Philology, lxxix, part iv, 26.

(4) Public Record Office C24/518 No. 10. The Cheshire Sheaf, 3rd Series, xvii, 22. British Library, Harley MS 2177, folio 10v.

(6) Information concerning the King’s School was kindly researched for me some years ago by Mr A. St. G. Walsh, a former member of staff. A. B. C. `Johniana’, The Eagle, xxiii (1902), 378-9. J. Venn, Alumni Cantabridgensis (1922), i. 401. Students Admitted to the Inner Temple (1877),131.

(7) Public Record Office, SP23/130 folios 31-8.

(8) P. Cunningham, Extracts from the accounts of the revels at court (London 1842) 31.

(12) Guildhall Library MS 6777/1.

(13) Harleian Society Register Series (1891), xvii, 295.

(14) The visitiation pedigrees usually give her name as Eleanor but it is clear from the burial record that she was known as Helen, British Library Harley MS 2177, folio 10v.

1545 PRIVILEGE OF KING FRANCIS I

FRANCIS by the grace of God King of France, to the Provost of Paris, the Bailiff of Rouen, the Seneschals of Lyons, Thoulouse and Poitou, and to all our justices and officers or to their deputies, and to each of them as to him belongeth, greeting.

On the part of our well-beloved and trusty Master Francis Rabelais, Doctor in Medicine of our University of Montpellier, it hath been set forth that the said petitioner having hereinbefore caused to be printed several books, especially two volumes of the heroic Deeds and Sayings of Pantagruel, not less useful than delectable, the printers have in several places corrupted and perverted the said books, to the great displeasure and detriment of the aforesaid petitioner, and the prejudice of the readers, wherefor he hath abstained from the publication of the remainder and continuation of the said heroic Deeds and Sayings. Nevertheless, being daily importuned by the learned and studious people in our kingdom, and requested to bring into use as by printing the said continuation, he hath petitioned Us to grant him the privilege that no one should have permission to print them or offer for sale any save those which he shall cause to be printed expressly by booksellers, and to whom he shall give his own true copies. And this for the space of ten consecutive years, beginning on the day and date of the printing of his said books. We therefore, these things considered, being desirous that good letters be promoted through our kingdom, to the profit and instruction of our subjects, have granted to the said petitioner privilege, leave, license and permission to cause to be printed and put in sale by such tried booksellers as he shall think fit his said books and works in continuation of the heroic Deeds of Pantagruel, beginning with the third volume, with power and authority to correct and review the two first books heretofore by him composed : and to make or cause to be made a new impression and sale of them, putting forth inhibitions and prohibitions in our name, on certain great penalties, confiscation of the books thus by them printed, and arbitrary amend to all printers and others to whom it shall belong, not to print and put in sale the books hereinbefore mentioned without the will and consent of the said petitioner within the term of six consecutive years [l] beginning on the day and date of the impression of his said books, on pain of confiscation of the said printed books and of arbitrary amend. To do this, we have given and do give to each and every of you, as to him shall belong, full power, commission and authority, and we request and require all our justices, officers and subjects by our presents that they cause, suffer and permit the said petitioner peaceably to enjoy and use this leave, privilege and commission, and that you in so doing be obeyed. For thus it is our pleasure it be done.

Given at Paris the nineteenth day of September in the year of grace one thousand five hundred and forty-five, and the thirty-first of our reign.

Signed : ” By order of the Council

DELAUNAY.”

and sealed on single label [2] with yellow wax.

1. six consecutive years. A little above, the document says ten consecutive years. The privilege was really given for six years. This privilege accompanied the edition of 1646.

2. On single label is when the seal is attached to a corner of the parchment which is cut for that purpose. On double label is when the seal is on a strip of parchment which is passed through the deed and doubled.

FRANCOYS PAR la grace de Dieu Roy de France, au Praevost de Paris, Bailly de Roüen, Seneschaulx de Lyon, Tholouse, Bordeaulx, & de Poictou, & a tous noz Justiciers, & officiers, ou a leurs Lieutenans, & a chascun d’eulx si comme a luy apartiendra salut. De la partie de nostre aimé & feal maistre Francoys Rabelais docteur en Medicine de nostre Université de Montpellier, nous a esté exposé, que icelluy suppliant ayant par cy davant baillé a imprimer plusieurs livres, mesmement deux volumes des faictz & dictz Heroïcques de Pantagruel, non moins utiles que delectables, les Imprimeurs auroient iceulx livres corrumpu & perverty en plusieurs endroictz, au grand deplaisir & detriment dudict suppliant, & praejudice des lecteurs, dont se seroit abstenu de mettre en public le reste & sequence des dictz faictz & dictz Heroïcques. Estant toutesfoys importuné journellement par les gens scavans & studieux de nostre Royaulme & requis de mectre en l’utilité comme en impression la dicte sequence: Nous auroit supplié de luy octroyer privilege a ce que personne n’eust a les imprimer ou mectre en vente fors ceulx qu’il feroit imprimer par libraires exprés, & aux quelz il bailleroit ses propres & vrayes copies. Et ce l’espace de dix ans consecutifz, a ii commancans au jour & dacte de l’impression de ses dictz livres. Pour quoy nous ces choses considerées desirans les bonnes letres estre promeues par nostre Royaulme a l’utilité & erudition de noz subjectz, avons audict suppliant donné privilege, congé, licence, & permission de faire imprimer & mectre en vente par telz libraires experimentez qu’il advisera, ses dictz livres & oeuvres consequens, des faictz Heroïcques de Pantagruel, commancans au troisiesme volume, avec povoir & puissance de corriger & revoir les deux premiers par cy davant par luy composez: & les mectre ou faire mectre en nouvelle impression & vente, faisans inhibitions & deffences de par nous sur certaines & grands peines, confiscation des livres ainsi par eulx imprimez, & d’admende arbitraire a tous imprimeurs & aultres qu’il appartiendra de non imprimer & mectre en vente les livres cy dessus mentionnez, sans le vouloir & consentement dudict suppliant dedans le terme de six ans consecutifz; commancans au jour & dacte de l’impression de ses dictz livres, sur poine de confiscation des dictz livres imprimez, & d’admende arbitraire. De ce faire vous avons chascun de vous si comme a luy apartiendra donné, & donnons plein povoir, commission & auctorité, mandons & commandons a tous noz justiciers, officiers & subjectz, que de noz praesens congé, privilege, & commission, ilz facent seuffrent, & laissent jouyr & user le dict suppliant paisiblement, & a vous en ce faisant estre obey. Car ainsi nous plaist il estre faict. Donné a Paris, le dixneufiesme jour de Septembre, l’an de grace, Mil cinq cens quarante cinq, & de nostre regne le xxxi. Ainsi signé par le conseil Delaunay . Et seellé sur simple queue de cire jaulne.

1550 PRIVILEGE OF KING HENRY II

HENRY by the grace of God King of France, to the Provost of Paris, the Bailiff of Rouen, the Seneschals of Lyons, Bordeaux, Dauphine, Poitou, and all our other Justices and Officers or their Deputies, and to each of them as to him shall belong health and love.

On the part of our dear and well-beloved Master Francis Rabelais, Doctor in Medicine, it hath been set forth to us that the said petitioner, having aforetimes given to be printed several books in Greek, Latin, French, and Tuscan, specially certain volumes of the heroic Deeds and Sayings of Pantagruel, not less useful than delectable, the printers had corrupted, depraved and perverted the said books in several places. Moreover that they had printed several other scandalous books in the name of the said petitioner, to his great displeasure, prejudice and ignominy, by him totally disavowed as false and supposititious : the which he desires under our good will and pleasure to suppress. He desireth withal to review and correct and to reprint anew the others his own works avowed, but depraved and disguised as aforesaid. Likewise to put into publication and sale the continuation of the heroic Deeds and Sayings of Pantagruel, thereto humbly requiring us to grant to him our letters-patent necessary and convenient for this.

Therefore it is that we, freely inclining unto the supplication and request of the said Master Francis Rabelais, and desiring to entreat him well and favourably in this matter, have to him, for these causes and other good considerations moving us hereto, permitted, accorded and granted, and of our certain knowledge, full power and royal authority do hereby permit, accord and grant by these presents that he have power and permission, by such printers as he shall think fit, to cause to be printed and again placed and exposed for sale all and every one of the said books and continuation of Pantagruel by him composed and undertaken, as well those which have already been printed and which shall be for this purpose revised and corrected by him, as also those which he purposeth to publish anew. Likewise that he have power to suppress those which are falsely attributed to him. And to the end that he have means to support the necessary expenses for the publication of the said impression, we have by these presents inhibited and forbidden most expressly, and we do hereby inhibit and forbid all other booksellers and printers in this our kingdom and others our lands and signories that they do not have to print or cause to be printed, place and expose for sale, any of the aforesaid books, old as well as new, during the time and term of ten years ensuing and consecutive, commencing on the day and date of the impression of the said books, without the freewill and consent of the said petitioner, and that under penalty of confiscation of the books which shall be found to have been printed to the prejudice of this our present permission and arbitrary amend.

We do therefore hereby will and command you and each one of you in his place and as to him it shall belong, that you entertain, guard and observe our present leave, licence and permissions, inhibitions and interdicts. And if any have been found to have contravened, proceed and cause process to be taken against them by the pains aforesaid and otherwise. And cause the said petitioner to enjoy and use fully and peaceably that which is contained hereabove during the said time to begin and everything as above is said, ceasing and causing to cease all troubles and hindrances to the contrary. For such is our pleasure, notwithstanding all ordinances, restrictions, commands or interdicts whatever contrary to this. And for that copies of these presents may be made in several and divers places we will that on the vidimus thereof made under the seal royal obedience be given as to this original present.

Given at Saint Germain in Laye the sixth day of August the year of grace one thousand five hundred and fifty and the fourth of our reign.

By order of the King.

Present — The Cardinal of Chatillon.

(Signed) Du THIER

HENRY par la grace de Dieu Roy de France, au Prevost de Paris, Bailly de Rouen, Seneschaulx de Lyon, Tholouze, Bordeaux, Daulphiné, Poictou, et à tous nos aultres justiciers & officiers, ou a leurs lieutenants, & a chascun d’eulx si comme a luy appartiendra, salut & dilection. De la partie de notre cher & bien ayme M. François Rabelais docteur en medicine, nous a esté expo- sé que icelluy suppliant ayant par cy devant baillé a imprimer plusieurs livres: en Grec, Latin, François, & Thuscan, mesmement certains volumes des faicts & dicts Heroïques de Pantagruel, non moins utiles que delectables: les Imprimeurs auroient iceulx livres corrompuz, depravez, & pervertiz en plusieurs endroictz. Auroient d’avantage imprimez plusieurs autres livres scandaleux, ou nom dudict suppliant, a son grand desplaisir, prejudice, & ignominie par luy totalement desadvouez comme faulx & supposez: lesquelz il desireroit soubs nostre bon plaisir & volonté supprimer. Ensemble les autres siens advouez, mais depravez & desguisez, comme dict est, reveoir & corriger & de nouveau reimprimer. Pareillement mettre en lumiere & vente la suitte des faicts & dicts Heroïques de Pantagruel. Nous humblement requerant surce, luy octroyer nos letres a ce necessaires & convenables. Pource est il que nous enclinans liberalement a la supplication & requeste dudict M. François Rabelais, exposant & desirans le bien & favorablement traicter en cest endroict. A icelluy pour ces causes & autres bonnes considerations a ce nous mouvans, avons permis accordé & octroyé. Et de nostre certaine science pleine puissance & auctorité Royal, permettons accordons & octroyons par ces presentes, qu’il puisse & luy soit loisible par telz imprimeurs qu’il advisera faire imprimer, & de nouveau mettre & exposer en vente tous & chascuns lesdicts livres & suitte de Pantagruel par luy composez & entreprins, tant ceulx qui ont ja esté imprimez, qui seront pour cest effect par luy reveuz & corrigez. Que aussi ceulx qu’il delibere de nouvel mettre en lumiere. Pareillement supprimer ceulx qui faulcement luy sont attribuez. Et affin qu’il ayt moyen de supporter les fraiz necessaires a l’ouverture de ladicte impression: avons par ces presen tes tresexpressement inhibé & deffendu, inhibons & deffendons a tous autres libraires & imprimeurs de cestuy nostre Royaulme, & autres nos terres & seigneuries, qu’ilz n’ayent a imprimer ne faire imprimer mettre & exposer en vente aucuns des dessusdicts livres, tant vieux que nouveaux durant le temps & terme de dix ans ensuivans & consecutifz, commençans au jour & dacte de l’impression desdicts livres sans le vouloir & consentement dudict exposant, & ce sur peine de confiscation des livres qui se trouverront avoir esté imprimez au prejudice de ceste nostre pre sente permission & d’amende arbitraire. Si voulons & vous mandons & a chascun de vous endroict soy & si comme a luy appartiendra, que nos presens congé licence & permission, inhibitions & deffenses, vous entretenez gardez & observez. Et si aucuns estoient trouvez y avoir contrevenu, procedez & faictes proceder a l’encontre d’eulx, par les peines susdictes & autrement. Et du contenu cy dessus faictes, ledict suppliant jouyr & user plainement & paisiblement durant ledict temps a commencer & tout ainsi que dessus est dict. Cessans & faisans cesser tous troubles & empeschemens au contraire: car tel est nostre plaisir. Nonobstant quelzconques ordonnances, restrinctions, mandemens, ou deffenses a ce contraires. Et pource que de ces presentes lon pourra avoir a faire en plusieurs & divers lieux, Nous voulons que au vidimus d’icelles, faict soubs seel Royal, foy soit adjoustée comme a ce present original. Donné a sainct Germain en laye le sixiesme jour d’Aoust, L’an de grace mil cinq cens cinquante, Et de nostre regne le quatreiesme.

Par le Roy, le cardinal de Chastillon praesent. Signé Du Thier.

Despite the privilège, and the volume’s dedication to Marguerite de Navarre, the Third Book (NRB 28), printed by the humanist Chrétien Wechel of Paris, was also banned in December 1546. Shortly thereafter, Rabelais himself fled France for Metz; ultimately the Royal Privilege of 1545 protected him neither against the Sorbonne, not against pirated editions. Nor was he on good terms with his new printer. In the Fourth Book, Rabelais appears to blame Wechel for a textual blunder in 1546 (OC 520), and there is evidence of a lawsuit between him and Wechel in a document of February 27, 1546. Not surprisingly, Rabelais did not employ Wechel for the definitive editions of the Third and Fourth Books in 1552.

These (NRB 36, 45-46) definitive editions of the Third and Fourth Books were bublished by Michel Fezandat of Paris and were protected by an even more remarkable privilège dated August 6, 1550. Granted under the aegis of a powerful protector, Odet de Chastillon, and reading like a humanist manifesto, the new Royal Privilege repeats many of the terms of 1545. It also covers Rabelais’s learned works and seeks to suppress the inauthentic works connected with Rabelais’s name. Notwithstanding the privilège authorizing its publication, however, the Fourth Book was quickly condemned. The king backed Rabelais in the face of this condemnation, virtually guaranteeing the volume’s succès de scandale, and the Fourth Book was reprinted, first by Fezandat and then illegally by others, in part to satisfy public curiosity about the controversy.

Rabelais’s death in 1553 prevented and test of his reinforced privilège and powerful patronage.