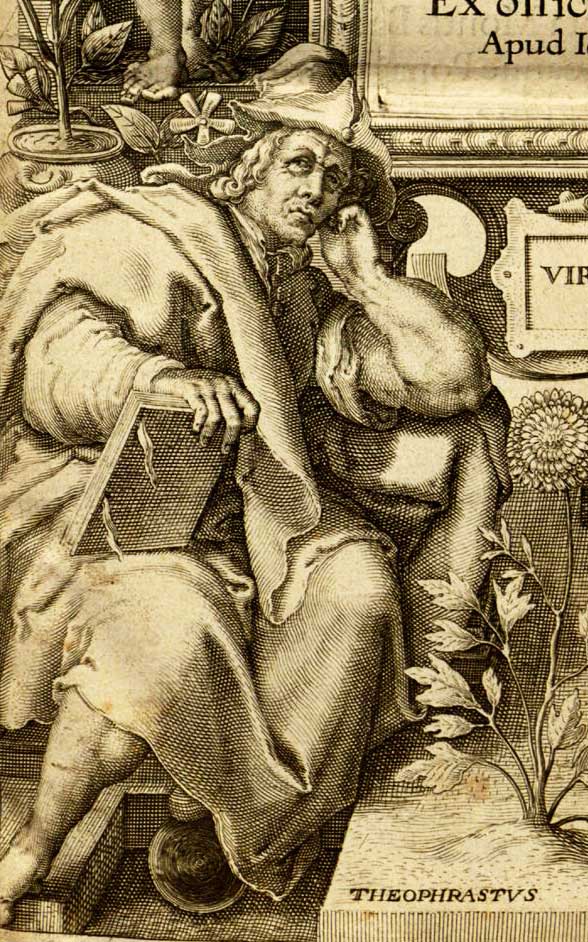

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (c. 371 – c. 287 BC), the Greek naturalist who was Aristotle’s successor at the Lyceum, appears by name at least seven times in Gargantua and Pantagruel

Notes

Theophrastus

Chap. xxi. Comment Gargantua feut institué par Ponocrates en telle discipline, qu’il ne perdoit heure du iour.

Au commencement du repas estoyt leur quelque histoire plaisante des anciennes prouesses: iusques à ce qu’il eut print son vin. Lors (sy bon sembloyt) on continuoyt la lecture: ou commenceoient à diviser ioyeusement ensemble, parlans pour les premiers moys de la vertus, proprieté/ efficace/ & nature, de tous ce que leur estoyt servy à table. Du pain/ du vin/ de l’eau/ du sel/ des viandes/ poissons/ fruictz/ herbes/ racines/ et de l’aprest d’ycelles. Ce que faisant aprint en peu de temps tous les passaiges à ce competens en Pline, Atheneus, Dioscorides, Galen, Porphyrius, Opianus, Polybieus, Heliodorus, Aristotele, Aelianus, & aultres. Iceulx propos tenens faisoient souvent, pour plus estre asseurez, apporter les livres sudictz à table. Et si bien & entierement retint en sa memoire les choses dictes, que pour lors n’estoit medicin, qui en sceust à la moytié tant comme ilz faifaisoient.

…

Le temps ainsi employé luy frotté, nettoyé, & refraischy d’habillemens, tout doulcement s’en retournoyt & passans apr quelques prez, ou aultres lieux herbuz visitoient les arbres & plantes, les conferens avec les livres des anciens qui en ont escript comme Theophraste, Dioscorides, Marinus, Pline, Nicander, Macer, & Galen. Et en emportoient leurs plenes mains au logis, desquelles avoyt la charge un ieune page nommé Rhizotome, ensemble des marrrochons, des pioches, cerfouetes, beches, tranches, & aultres instrumens requis à bien arborizer.

Comment frere Jan joyeusement conseille Panurge

«Ne me allguez poinct l’Indian tant celebré par Theophraste, Pline et Athenæus, lequel, avecques l’ayde de certaine herbe, le faisoit en un jour soixante de dix fois et plus.»

[Prodigiosa sunt quae circa hoc tradidit Theophrastus, auctor alioqui gravis, septuageno coitu durasse libidinem contactu herbæ cujucdam, cujus nomen genusque non posuit.» Pline, H. N., 26.63. — Cf .Théophraste, «de herba ab Indo quodam allata, qua qui usi feurint septuageno coire possent », Hist. plant., 9,20, et Athénée, I, § 32. (Delaunay)

Panurge’s testiculatory ability

Do not here produce ancient examples of the paragons of paillardice, and offer to match with my testiculatory ability the Priapaean prowess of the fabulous fornicators, Hercules, Proculus Caesar, and Mahomet, who in his Alkoran doth vaunt that in his cods he had the vigour of three score bully ruffians; but let no zealous Christian trust the rogue,–the filthy ribald rascal is a liar. Nor shalt thou need to urge authorities, or bring forth the instance of the Indian prince of whom Theophrastus, Plinius, and Athenaeus testify, that with the help of a certain herb he was able, and had given frequent experiments thereof, to toss his sinewy piece of generation in the act of carnal concupiscence above three score and ten times in the space of four-and-twenty hours.

Sayrion

The Greeks speak of a satyrion that has leaves like those of the lily, but red, smaller, and springing from the ground not more than three in number, a smooth, bare stem a cubit high, and a double root, the lower, and larger, part favouring the conception of males, the upper, and smaller, the conception of females. Yet another kind of satyrion they call erythraicon, saying that its seed is like that of the vitex, but larger, smooth and hard; that the root is covered with a red rind, and containsa a white substance with a sweetish taste, and that the plant is generally found in hilly country. They tell us that sexual desire is aroused if the root is merely held in the hand, a stronger passion, however, if it is taken in a dry wine, that rams also and he-goats are given it in drink when they are too sluggish, and that it is given to stallions from Sarmatiab when they are too fatigued in copulation because of prolonged labour; this condition is called prosedamum. The effects of the plant can be neutralized by doses of hydromel or lettuce. The Greeks indeed always, when they wish to indicate this aphrodisiac nature of a plant, use the name satyrion, so applying it to crataegis, thelygonon, and arrenogonon, the seeds of which resemble testicles. Again, those carrying on their persons the pith of tithymallus branches are said to become thereby more excited sexually. The remarks on this subject made by Theophrastus [See H.P. IX 18, 9], generally a weighty authority, are fabulous. He says that the lust to have intercourse seventy times in succession has been given by the touch of a certain plant whose name and kind he has not mentioned.

Theophrastus

He must have those hushed, still, quiet, lying at a stay, lither, and full of ease, whom he is able, though his mother help him, to touch, much less to pierce with all his arrows. In confirmation hereof, Theophrastus, being asked on a time what kind of beast or thing he judged a toyish, wanton love to be? he made answer, that it was a passion of idle and sluggish spirits.

Theophrastus

Theophrastus believed and experienced that there was an herb at whose single touch an iron wedge, though never so far driven into a huge log of the hardest wood that is, would presently come out; and it is this same herb your hickways, alias woodpeckers, use, when with some mighty axe anyone stops up the hole of their nests, which they industriously dig and make in the trunk of some sturdy tree.

…

In short, since elders grow of a more pleasing sound, and fitter to make flutes, in such places where the crowing of cocks is not heard, as the ancient sages have writ and Theophrastus relates; as if the crowing of a cock dulled, flattened, and perverted the wood of the elder, as it is said to astonish and stupify with fear that strong and resolute animal, a lion.

Theophrastus

Pan. By Priapus, they have the Indian herb of which Theophrastus spoke, or I’m much out. But, hearkee me, thou man of brevity, should some impediment, honestly or otherwise, impair your talents and cause your benevolence to lessen, how would it fare with you, then? Fri. Ill.

Theophrastus

Behind him stood a pack of other philosophers, like so many bums by a head-bailiff, as Appian, Heliodorus, Athenaeus, Porphyrius, Pancrates, Arcadian, Numenius, Possidonius, Ovidius, Oppianus, Olympius, Seleucus, Leonides, Agathocles, Theophrastus, Damostratus, Mutianus, Nymphodorus, Aelian, and five hundred other such plodding dons, who were full of business, yet had little to do; like Chrysippus or Aristarchus of Soli, who for eight-and-fifty years together did nothing in the world but examine the state and concerns of bees.

Textual Authorities for Enquiry into Plants

Wimmer divides the authorities on which the text of the περὶ φυτῶν ἱστορία is based into three classes:—

First Class:

U. Codex Urbinas: in the Vatican. Collated by Bekker and Amati; far the best extant MS., but evidently founded on a much corrupted copy. See note on 9. 8. 1.

P2. Codex Parisiensis: at Paris. Contains considerable excerpts; evidently founded on a good MS.; considered by Wimmer second only in authority to U. (Of other collections of excerpts may be mentioned one at Munich, called after Pletho.)

Second Class:

M (M1, M2). Codices Medicei: at Florence. Agree so closely that they may be regarded as a single MS.; considered by Wimmer much inferior to U, but of higher authority than Ald.

P. Codex Parisiensis: at Paris. Considered by Wimmer somewhat inferior to M and V, and more on a level with Ald.

mP. Margin of the above. A note in the MS. states that the marginal notes are not scholia, but variae lectiones aut emendationes.

V. Codex Vindobonensis: at Vienna. Contains the first five books and two chapters of the sixth; closely resembles M in style and readings.

Third Class:

Ald. Editio Aldina: the editio princeps, printed at Venice 1495–8. Believed by Wimmer to be founded on a single MS., and that an inferior one to those enumerated above, and also to that used by Gaza. Its readings seem often to show signs of a deliberate attempt to produce a smooth text: hence the value of this edition as witness to an independent MS. authority is much impaired.

(Bas. Editio Basiliensis: printed at Bâle, 1541. A careful copy of Ald., in which a number of printer’s errors are corrected and a few new ones introduced (Wimmer).

Cam. Editio Camotiana (or Aldina minor, altera): printed at Venice, 1552. Also copied from Ald., but less carefully corrected than Bas.; the editor Camotius, in a few passages, altered the text to accord with Gaza’s version.)

G. The Latin version of Theodore Gaza,1 the Greek refugee: first printed at Treviso (Tarvisium) in 1483. A wonderful work for the time at which it appeared. Its present value is due to the fact that the translation was made from a different MS. to any now known. Unfortunately however this does not seem to have been a better text than that on which the Aldine edition was based. Moreover Gaza did not stick to his authority, but adopted freely Pliny’s versions of Theophrastus, emending where he could not follow Pliny. There are several editions of Gaza’s work: thus

G. Par. G. Bas. indicate respectively editions published at Paris in 1529 and at Bâle in 1534 and 1550. Wimmer has no doubt that the Tarvisian is the earliest edition, and he gives its readings, whereas Schneider often took those of G. Bas.

Vin. Vo. Cod. Cas. indicate readings which Schneider believed to have MS. authority, but which are really anonymous emendations from the margins of MSS. used by his predecessors, and all, in Wimmer’s opinion traceable to Gaza’s version. Schneider’s so-called Codex Casauboni he knew, according to Wimmer, only from Hofmann’s edition.

Dendromalache

Théophraste, Histoire des plantes, XV, v, Rabelais confondant vraisemblablement la plante décrite par Théophraste avec la δενδρομαλάχη des Géoponiques (XV, v, 5) de Galien (voir Tiers livre, ed. Lefranc, n. 19, p. 340). L’exemplaire des livres VI-IX, Theophrasti de Suffruticibus, herbisque

et frugibus libri quattuor, Theodora gaza interprete, conservé à la Réserve de la Bibliotheque nationale, offre une note autographe de Rabelais en titre.

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (c. 371 – c. 287 BC), a Greek native of Eresos in Lesbos, was the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He came to Athens at a young age and initially studied in Plato’s school. After Plato’s death, he attached himself to Aristotle. Aristotle bequeathed to Theophrastus his writings and designated him as his successor at the Lyceum. Theophrastus presided over the Peripatetic school for 36 years, during which time the school flourished greatly. He is often considered the father of botany for his works on plants.