Notes

Salamandra

A salamander unharmed in the fire. Koninklijke Bibliotheek, KB, KA 16, Folio 126r

Salamander

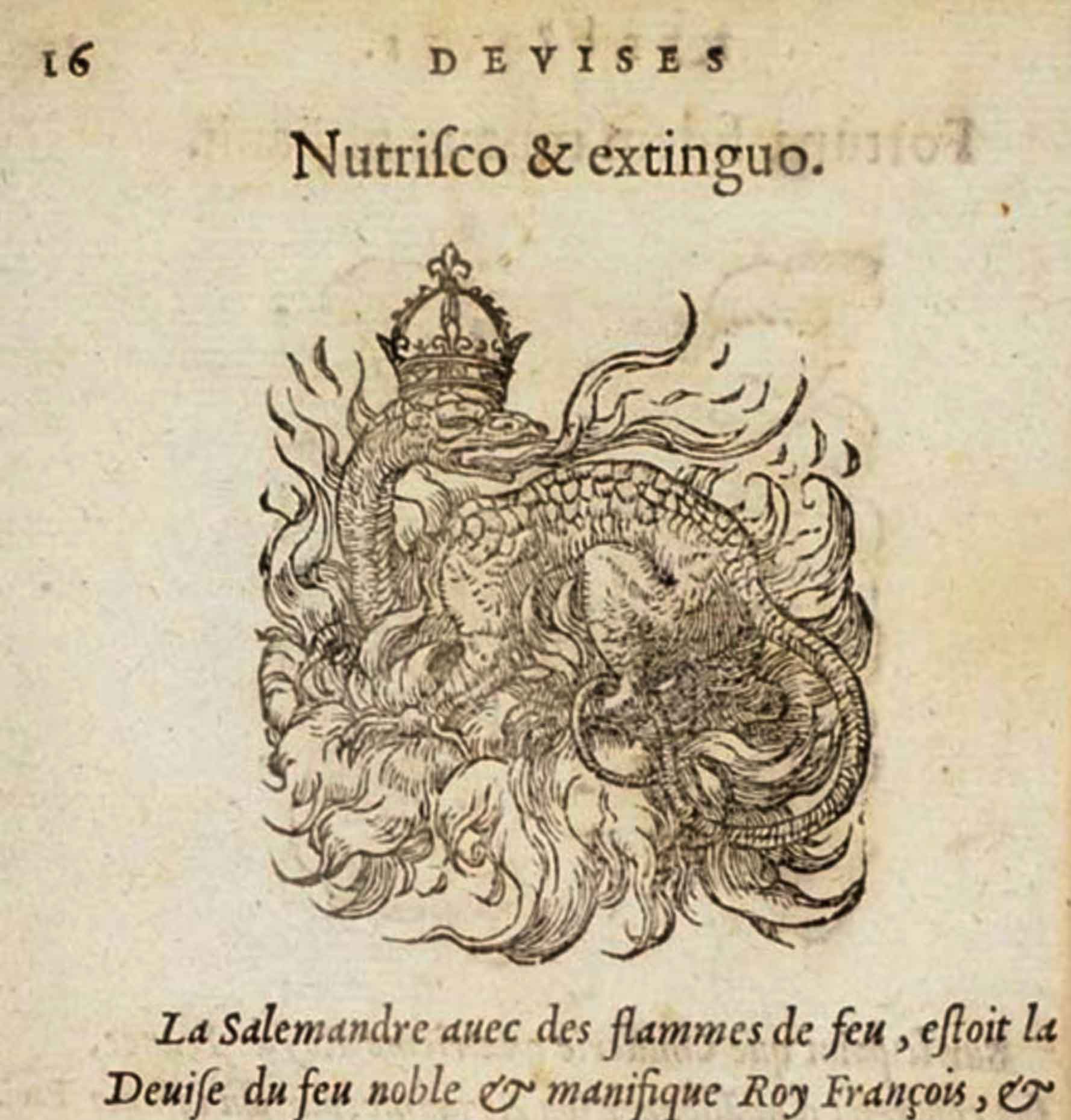

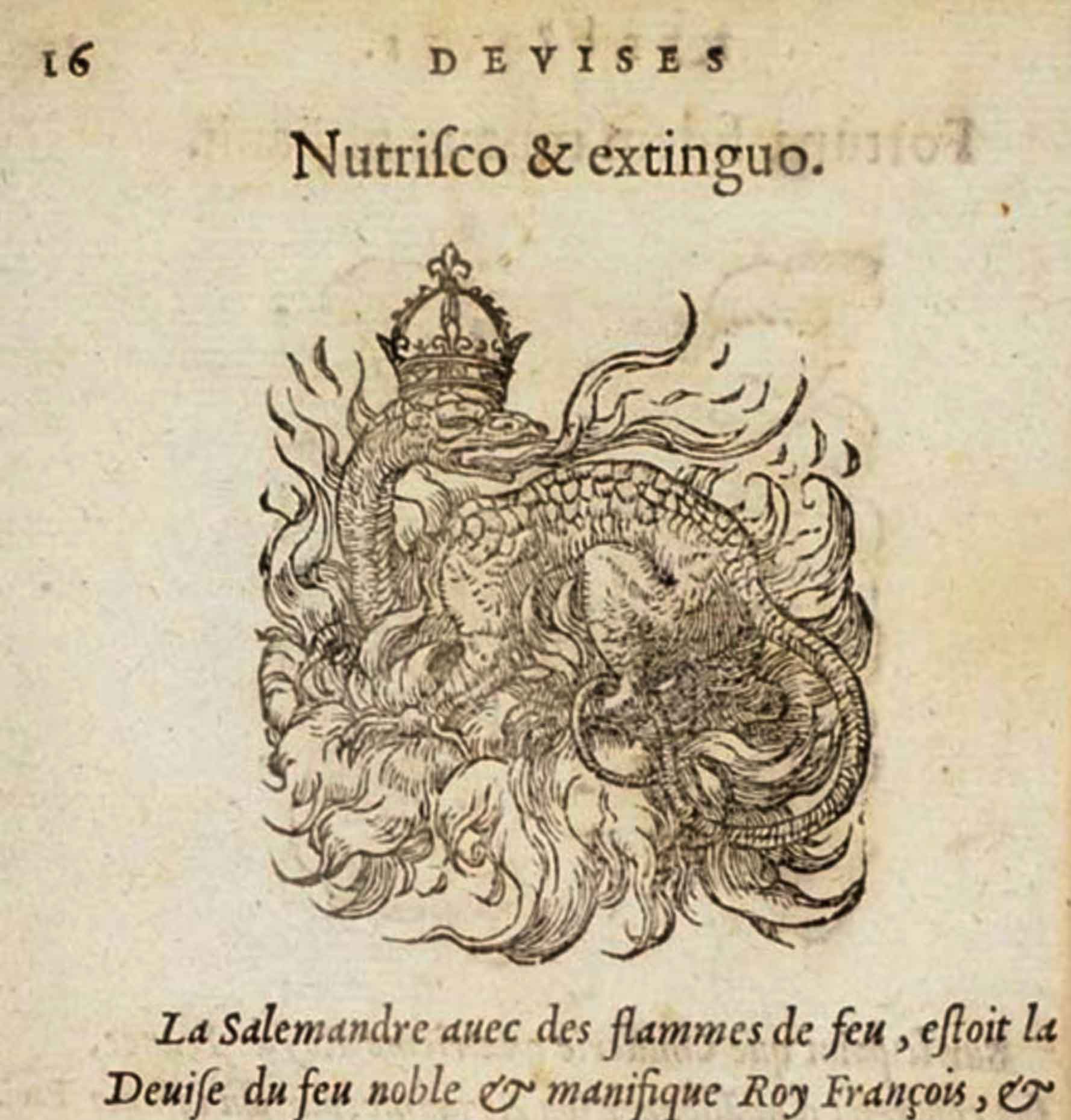

Nutrisco & extinguo. La Salemandre avec des flammes de feu, estoit la Devise du feu noble & manifique Roy François

Paradin, Claude (ca. 1510–1573),

Devises heroïques. Lyons: Jean de Tournes and Guillaume Gazeau, 1557.

French Emblems at Glasgow

Salamander

Nutrisco et extinguo (I nourish and extinguish)

The salamander, device of François I.

Bury Palliser, Fanny (1805-1878),

Historic Devices, Badges, and War-cries. S. Low, Son & Marston, 1870.

Google Books

Salamander

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553),

Œuvres de Rabelais. Tome Premier [Gargantua, Pantagruel, Tiers Livre]. Gustav Doré (1832–1883), illustrator. Paris: Garnier Frères, 1873. p. 465.

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Salamander

The salamander, badge of Francis I of France, with his motto: “Nutrisco et extinguo” (“I nourish and extinguish”) – Azay-le-Rideau Castle – Loire Valley (Indre-et-Loire), France

Salamandre

Anguem ex medulla hominis spinae gigni accepimus a multis. pleraque enim occulta et caeca origine proveniunt, etiam in quadripedum genere, sicut salamandrae, animal lacertae figura, stellatum, numquam nisi magnis imbribus proveniens et serenitate deficiens.1 huic tantus rigor ut ignem tactu restinguat non alio modo quam glacies. eiusdem sanie, quae lactea ore vomitur, quacumque parte corporis humani contacta toti defluunt pili, idque quod contactum est colorem in vitiliginem mutat.

We have it from many authorities that a snake may be born from the spinal marrow of a human being. For a number of animals spring from some hidden and secret source, even in the quadruped class, for instance salamanders, a creature shaped like a lizard, covered with spots, never appearing except in great rains and disappearing in fine weather. It is so chilly that it puts out fire by its contact, in the same way as ice does. It vomits from its mouth a milky slaver, one touch of which on any part of the human body causes all the hair to drop off, and the portion touched changes its colour and breaks out in a tetter.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 3: Books 8– 11. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1940. 10.86.

Loeb Classical Library

Salamander

16 Nutrisco & extinguo.

La Salemandre avec des flammes de feu, estoit la Devise du feu noble & manifique Roy François, & aussi au paravant de Charles Conte d’Angoulesme son pere. Pline dit que tell beste par la froidure esteint le feu comme glace, autres disent qu’elle peut vivre en icelui, et la commune voix qu’elle s’en paist. Tant y ha qu’il me souvient avoir vu une Medaille en bronze dudit feu Roy, peint en jeune adolescent, au revers de laquelle estoit cette Devise de la Salemandre enflammee, avec ce mot Italien: Nudrisco il buono, & spego il reo. Et davantage outre tant de lieus et Palais Royaus, ou pour le jourdhui est enlevee, je l’ay vuë aussi en riche tapisserie à Fonteinebleau, acompagnee de rel Distique:

Ursus astrox, Aquilæq; leves, & tortilis Anguis: Cesserunt flammæ iam Salamandra tuæ.

Paradin, Claude (ca. 1510–1573),

Devises heroïques. Lyons: Jean de Tournes and Guillaume Gazeau, 1557.

French Emblems at Glasgow

Alcofribas

Alcofribas. A greedie gultton; a great devourer.

Alebrenne. A Salamander.

Alebromantic. Divination by barley meale mixed with wheat.

Cotgrave, Randle (–1634?),

A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongue. London: Adam Islip, 1611.

PBM

salamandre

Comme la salamandre étoit la devise ou l’emblème de François Ier, il doit y avoir ici une allusion à ce prince.

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553),

Œuvres de Rabelais (Edition Variorum). Tome Cinquième. Charles Esmangart (1736–1793), editor. Paris: Chez Dalibon, 1823. p. 293.

Google Books

Salamander

Francis I. His well-known device was the salamander, surrounded by flames, with the motto, Nutrisco et extinguo, “I nourish and extinguish,” alluding to the belief current in the middle ages that the salamander had the faculty of living in fire; and also, according to Pliny, of extinguishing it. He says — “He is of so cold a complexion, that if hee doe but youch the fire, hee will quench it as presently as if yce were put into it (Book x., ch. 67).

This motto appears to be a somewhat obscure rendering of one on a medal of Francis, when Comte d’Angoulême, dated 1512: “Nutrisco el buono, stengo el reo,” meaning that a good prince protects the good and expels the bad. Some insist that it was the motto of his fatherl while Mézeerai tells us that it was his tutor, Gouffier, Marquis de Boisy, who, seeing the violent and ungovernable spirit of his pupil, not unmixed with good and useful impulses, selected the salamander for his device, with its appropriate motto. This device appears on all the palaces of Francis I. At Fontainebleau and the Châteaux of the Loire, it is everywhere to be seen; at Chambord, there are nearly four thousand. On the Château d’Azay the salamander is acccompanied by the motto, Ung seul desir; at the “Maison de François I,” at Orleans, built for the Demoiselle d’Heillie, afterwards Duchesse d’Etampes, we find it intermixed with F’s and H’s.

At the meeting of the Field of the Cloth of Gold, the king’s guard at the tournament was clothed in blue and yellow, with the salamander embroidered thereon. In the already quoted inventory of the Castle of Edinburgh is —

“Ane moyane of fonte markit with the sallamandre;”

“Ane little gallay cannon of fonte markit with sallamandre;”

and many others.

Bury Palliser, Fanny (1805-1878),

Historic Devices, Badges, and War-cries. S. Low, Son & Marston, 1870. P. 115.

Google Books

Salamandre

“Une bieste i r’a Salamandre

Qui en feu vist et si s’en paist,

De cete bieste laine si nast

Dont on fait chaintures et dras

Qu’ai feu durent et n’ardent pas.”

— Gauthier de Metz, L’Image du Monde (1245)

Hence it appears, according to this notice, that asbestos cloth was derived from the salamander.

Bury Palliser, Fanny (1805-1878),

Historic Devices, Badges, and War-cries. S. Low, Son & Marston, 1870. p. 115.

Google Books

Salamander

“Huic tantus rigor ut ignem tactu extinguat non alio modo qual glacies” (Pliny x. 67, § 86).

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

salamander

Salamandra maculosa Laur. (Batraciens Anoures). La légende antique prétendait que la salamandre peut braver les flammes et les éteindre. «Huic tantus rigor, ut ignem restinguat non alio modo qual glacies». (Pline, X, 86.) Dioscoride s’était déjà prononcé contre cette fable: «Salamandra lacertæ genus est, iners, varium, quod frustra creditum est ignibus non uri». (L. II, ch. 54.) Albert le Grand, plus tard, et Rabelais seront de son avis. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 372.

Internet Archive

Salamandre

Selon la légende antique, la salamandre peur braver les flammes et les éteindre. François Ier en avait fait son emblème.

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553), Œuvres complètes. Mireille Huchon, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1994. p. 511, n. 3.

Salamandre

Elle passait pour éteindre le feu (Pline, X, 67); légende extrêmement répandue.

Rabelais, François (1494?–1553), Le Tiers Livre. Edition critique. Jean Céard, editor. Librarie Général Français, 1995. p. 472.

Salamander

When I was about five years of age, my father, happening to be in a little room in which they had been washing, and where there was a good fire of oak burning, looked into the flames and saw a little animal resembling a lizard, which could live in the hottest part of that element. Instantly perceiving what it was, he called for my sister and me, and after he had shown us the creature, he gave me a box on the ear. I fell a-crying while he, soothing me with caresses, spoke these words: ‘My dear child, I do not give you that blow for any fault you have committed, but that you may recollect that the little creature you see in the fire is a salamander; such a one as never was beheld before to my knowledge.’ So saying he embraced me, and gave me some money. — Benvenuto Cellini

The salamander (the name possibly coming from the Greek salambe meaning ‘fireplace’) was often visualized as a small dragon or lizard. But, what set the salamander apart from other lizards or serpents was the fact that it was a fire elemental. According to Aristotle and Pliny, the salamander not only resisted fire, but could extinguish it and would charge any flame that it saw as if it were an enemy. Some thought that the reason the salamander was able to withstand and extinguish fire, was that it was incredibly cold, and it would put out fire on contact. The salamander was also considered to be very poisonous, so much so, that a person would die from eating the fruit form a tree around which a salamander had entwined itself.

The foundation of its fire-resistant powers may be based on the fact that the real salamander secretes milky juice form the pores of its body when its irritated. This would doubtless defend the animal for a few moments from fire. Salamanders also are hibernating creatures who often retire to hollow trees or other cavities in the winter, where it coils himself up and remains in a torpid state until the spring. It was therefore sometimes carried in with the fuel to the fire, and the salamander would wake up with only enough time to put for all of its faculties for its defense.

Long, Don, Monsters.

Salamander

Early in the 19th century one key idea was introduced [in the building of safes], the double skin. It was realised that 100mm of insulation between the outer wall and the inner wall would provide great thermal insulation and protect the contents if caught in a fire. The most common insulation used was sawdust, though even greater protection came from filling the gap with water, an idea patented by Thomas Milner in 1830 (Milner is to this day one of the main British safe companies). The name ‘safe’ came from these new fireproof cabinets. At the time it was seen as astonishing that the contents of these safes could survive the heat of a fire (they were sometimes called Salamanders) and safe companies often staged public demonstrations, mounting their safes on large bonfires. Strauss was actually commissioned to write some music for one of these events, he called it the ‘Feufest Polka’.

Hunkin, Tim, lllegal Engineering.

salamander

salamander. Also salamandre [adopted from French salamandre (12th century), adaptation of Latin salamandra, adopted from Greek salamandra.]

A lizard-like animal supposed to live in, or to be able to endure, fire. Now only allusive.

1340 Dan Michel’s Ayenbite of Inwyt. 167 Þe salamandre þet leueþ ine þe uere.

C. 1430 John Lydgate Min. Poems (Percy Soc.) 170 And salamandra most felly dothe manace.

1481 William Caxton Myrrour of the Worlde. ii. vi. 74 This Salemandre berith wulle, of whiche is made cloth and gyrdles that may not brenne in the fyre.

1590 Greene Roy. Exch. Wks. (Grosart) VII. 230 The Poets… seeing Louers scorched with affection, likeneth them to Salamanders.

A. 1591 H. Smith Serm. (1637) 9 Like the Salamander, that is ever in the fire and never consumed.

1616 R. C. Cert. Poems in Times’ Whistle, etc. (1871) 119 Yet he can live noe more without desire, Then can the salamandra without fire.

1634 Sir T. Herbert Trav. 20 The Aery Camelion and fiery Salamander are frequent there [sc. in Madagascar].

1681 Flavel Meth. Grace xxvii. 464 Sin like a Salamander can live to eternity in the fire of God’s wrath.

1688 R. Holme Armoury ii. 205/1, I have some of the hair, or down of the Salamander, which I have several times put in the Fire, and made it red hot, and after taken it out, which being cold, yet remained perfect wool.

1711 Hearne Collect. (O.H.S.) III. 129 He had 2 Salamanders, which lived 2 hours in a great Fire.

1864 Kingsley Rom. & Teut. iv. 131 That he will henceforth [in the island of Volcano] follow the example of a salamander, which always lives in fire.

1525. La Grande Maîtress

p 28. Il est probable que la Grande Maîtresse a subi un radoub, peut-être entre la fin 1529 et 1531. Le carénage précédent a eu lieu en 1525 et Jerôme Doria fait état d’une périodicité de quatre ans pour les carénages. Un document mon daté de la Bibliothèque Impériale de Vienne confirme l’opération: «Lettres permettant à frère Claude d’Ancienville, chevalier de Sant-Jean de Jerusalem, commandeur a’Auxerre, capitaine de la nef la Grande-Maîtresse, d’acheter en Dauphiné et en Provence les bois et cordages nécessaires au radoub de ladite nef, et de les faire mener à Marseille par l’Isère, le Rhône et la Durance sans payer de droits.»

p. 10. Ce fut une grande perte, car cette nef étrait grosse comme une caraque, bien garnie en artillerie au point qu’il n’existait pas à Gênes de semblable caraque.

Le nom de Grande Maîtresse, ou plus préciseément cette appellation, indique que le bâtiment appartenait, ou, plus exactement, avait appartenu, au Grand Maître de France. Il est mentionnée pour des opérations que se déroulent en Méditerranée en 1520, 1525, 1526, 1528 et 1529.

Les inventaires effectués au moment de la vente montrent que la nef était équipée d’une puissante artillerie de bronze, dont plusieurs pièces sont ornées de la salamandre, par exemple: Plus troys couleuvrines bastardes à la samalandre, poysans iii milliers ou environ chacun… Plus deux coulouvrines moyeners à la salamandre, pesans chacune xii quintaulx ou environ.

p. 172. Ancienville, Claude d’ — seigneur de Villiers. Chevalier et commandeur de l’ordre de Saint Jean de Jérusalem, fils de Claude d’Ancienville et d’Andrée de Saint-Benôit, frère d’Antoine et de Jacques d’Ancienville.

Il quitte Rhodes assiégée à bord de son brigantin le 18 juin 1522, apportant à François Ier un message du grand-maitre Villiers de l’Isle Adam qui demande des secours d’urgence.…. En juillet 1527, il est commandant de la Grand Maîtress, qui est à Toulon…. En 1530, des lettres royales l’autorisent à acheter en Dauphiné et en Provence les bois et cordages nécessaires au radoub de la nef et de les faire mener à Marseille.

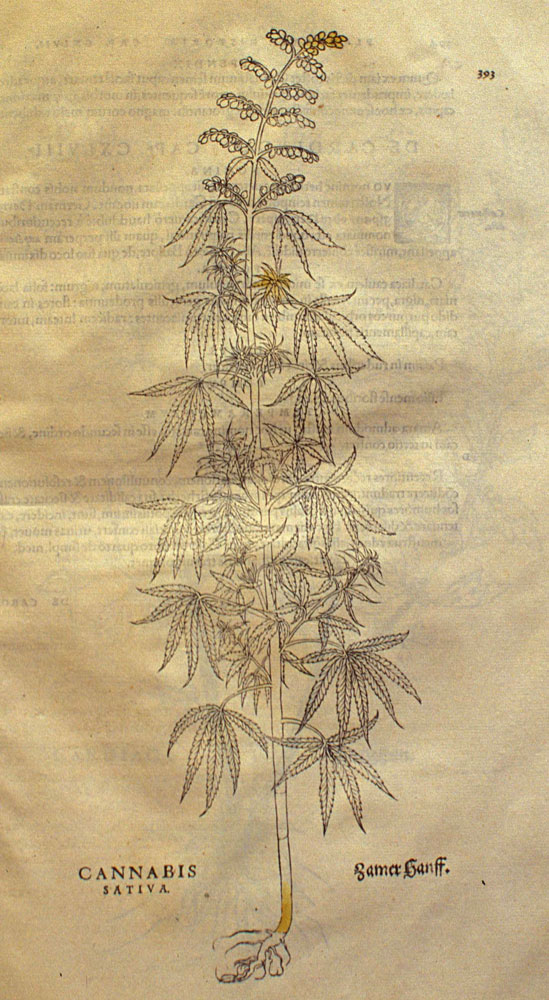

p. 175. Ancienville, Jacques d’, seigneur de Révillon. Il reçoit, en juin 1537, la permission de faire conduire de Lyon à Marseille sans payer aucun droit de travers, péage et autres, pour l’armement des galères dont il a la charge, 250 quintaux de fer… 500 quintaux de cordages or chanvre….

[Historiquement, le quintal équivalait généralement à 100 livres. Le quintal français ancien valait 100 livres anciennes, donc environ 48,951 kilogrammes. Il faut toutefois noter que le quintal était encore utilisé au début des années 1960 à Strasbourg (67) pour mesurer 50 kg de charbon acheté en sacs.

Les poids de marc constituent un système d’unités de masse utilisé depuis le milieu du xive siècle et sous l’Ancien Régime français. Les poids de marc moyens sont organisés par la pile dite de Charlemagne, un ensemble de pierres de balance en godets s’empilant l’une dans l’autre d’un poids total de 50 marcs, soit environ 12¼ kilogrammes.

La livre des poids de marc ou livre de Troyes, attestée depuis le début du xiiie siècle, valut dans tout le royaume à partir de 1266. La livre de Troyes est en principe douze dixièmes de la livre carolingienne. Cette dernière fut instaurée en 793 par Charlemagne.]

Guérout, Max,

La Grande Maîtresse, nef de François Ier. Recherches et documents d’archives. Bernard Liou, author. Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 2001.

Google Books

Salamandre

La salamandre, baffie ou lebraude est un amphibien légendaire qui était réputé pour vivre dans le feu et s’y baigner, et ne mourir que lorsque celui-ci s’éteignait. Mentionnée pour la première fois par Pline l’Ancien, la salamandre devint une créature importante des bestiaires médiévaux ainsi qu’un symbole alchimique et héraldique auquel une profonde symbolique est attachée. Ainsi, Paracelse (1493-1541) en faisait l’esprit élémentaire du feu, sous l’apparence d’une belle jeune femme vivant dans les brasiers. D’autres légendes plus tardives en font un animal extrêmement venimeux, capable d’empoisonner l’eau des puits et les fruits des arbres par sa seule présence.