of his arsenal of Thalassa;

Original French: de ſon arſenac de Thalaſſe:

Modern French: de son arsenac de Thalasse:

The port of Thalasse is mentioned in Chapter 49.

Original French: de ſon arſenac de Thalaſſe:

Modern French: de son arsenac de Thalasse:

The port of Thalasse is mentioned in Chapter 49.

Original French: de ſes carracons, nauires, gualeres, gualiõs, brigãtins, fuſtes,

Modern French: de ses carracons, navires, gualères, gualions, brigantins, fustes,

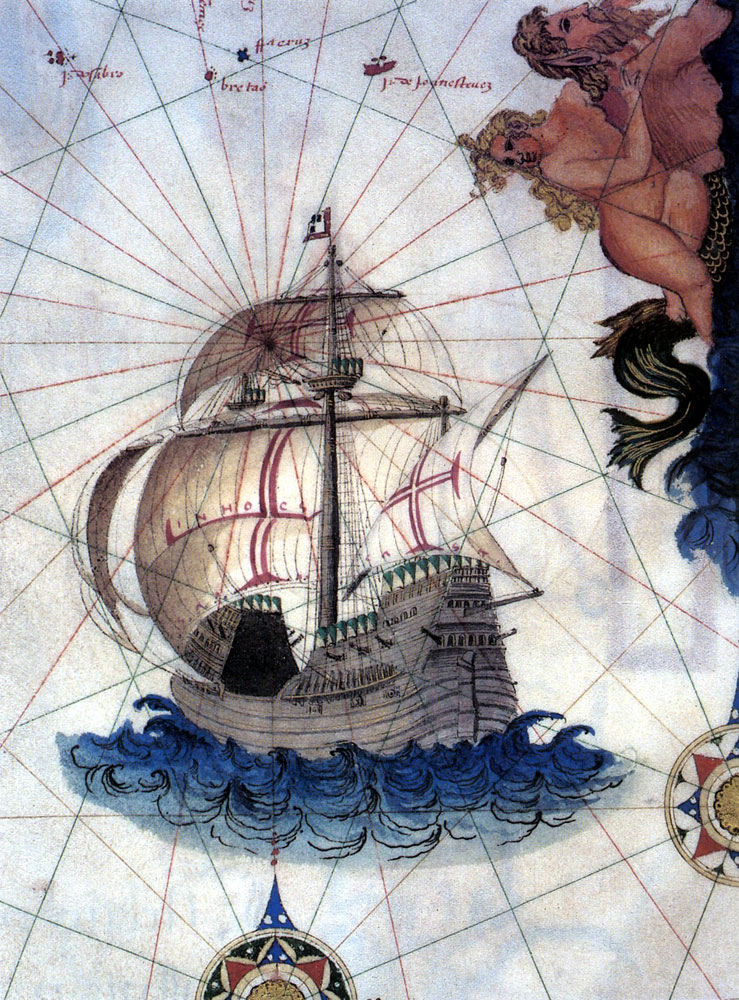

Sebastião Lópes (15??–1596). A Portuguese nau (carrack) as depicted in a map made in 1565.

A carrack or nau was a three- or four-masted sailing ship developed in the 15th century by the Genoese for use in commerce, differing from the Venetians who favoured Galleys. Those ships became part of the illumanauty then widely used by Europe’s 15th-century maritime powers. It had a high rounded stern with large aftcastle, forecastle and bowsprit at the stem. It was first used by the Portuguese for oceanic travel, and later by the Spanish, to explore and map the world. It was usually square-rigged on the foremast and mainmast and lateen-rigged on the mizzenmast.

Carracks were ocean-going ships: large enough to be stable in heavy seas, and roomy enough to carry provisions for long voyages. They were the ships in which the Portuguese and the Spanish explored the world in the 15th and 16th centuries. In Genoese the ship was called caracca or nao (ship), in Portuguese nau, while in Spanish carraca or nao. In French it was called a caraque or nef. The name carrack probably derives from the Arab Harraqa , a type of ships that appeared first time along the shores of the Tigris and Euphrates around the 9th century.

As the forerunner of the great ships of the age of sail, the carrack was one of the most influential ship designs in history; while ships became more specialized, the basic design remained unchanged throughout the age of sail.

Jacques Cartier first navigated the Saint Lawrence River in 1535 in the carrack Grande Hermine

Vaisseaux marchands.

A ship of 2000 tons burden. Cf. i. 16.

Flûtes.

Small vessels used in the Mediterranean carrying [?] sails and oars.

Grande carraque. De l’italien caraccone.

Petite galère, à voiles et à rames. Du vénitien fusta. Sur ces termes nautiques, voir R.E.R., VIII, p. 156.

1545: Au moys d’octobre suivant les grands carracons que le roy [Françoys premier] avoit faict venir de Gennes en Italie pour la guerre contre l’Anglois arrivèrent sur les vazes de cette ville, chargés de munitions de guerre qui estoient pour l’armée navale de la reconqueste de Boulongne…

Original French: pareillement d’icelluy feiſt couurir les pouppes, prores, fougons, tillacs, courſies, & rambardes

Modern French: pareillement d’icelluy feist couvrir les pouppes, prores, fougons, tillacs, coursies, & rambardes

Proues.

Cuisines.

Galeries pratiquées de la prou à la poupe d’une galère.

Garde-fou de la [?] dunette

Fr. Coursies, the passage-planks (1-1/2 ft. broad), from stem to stern, between the rowers of a galley.

Fr. rambades

Rambarde: f. The bend, or wale of a Galley.

Prores: Proue. Néologisme; du lat. prora, même sens.

Fougons: Cuisine. Du véntien fogon.

Coursies: Passerelle allant de la poupe à la proue d’une galère, entre les bancs des rameurs. De l’italien corsia.

Rambades: Château d’avant. De l’italien rambata.

See Chapter 49:

Peu de jours après Pantagruel… arriva au port de Thalasse près Sammalo, accompaigné de… frère Ian des entommeures abbé de Thélème…”

Theleme is also mentioned in Chapter 51:

Taprobrana a veu Lappia: Iava a veu les mons Riphées: Phebol voyra Thelème

Ce rappel de Thélème rattache Le Tiers Livre au Gargantua. Le Pantagruelion comme l’abbaye de Thélème exprime un idéal de la sagesse rabelaisienne.

Original French: tous les huys, portes, feneſtres, gouſtieres, larmiers, & l’ambrun

Modern French: tous les huys, portes, fenestres, goustières, larmiers, & l’ambrun

14. The larch is known only to the provincials on the banks of the river Po and the shores of the Adriatic Sea. Owing to the fierce bitterness of its sap, it is not injured by dry rot or the worm. Further, it does not admit flame from fire, nor can it burn of itself; only along with other timber it may burn stone in the kiln for making lime. Nor even then does it admit flame or produce charcoal, but is slowly consumed over a long interval. For there is the least admixture of fire and air, while the moist and the earthy principles are closely compressed. It has no open pores by which the fire can penetrate, and repels its force and prevents injury being quickly done to itself by fire. Because of its weight it is not sustained by water; but when it is carried, it is placed on board ship, or on pine rafts.

15. We have reason to inquire how this timber was discovered. After the late emperor Caesar had brought his forces into the neighbourhood of the Alps, and had commanded the municipalities to furnish supplies, he found there a fortified stronghold which was called Larignum. But the occupants trusted to the natural strength of the place and refused obedience. The emperor therefore commanded his forces to be brought up. Now before the gate of the stronghold there stood a tower of this wood with alternate cross-beams bound together like a funeral pyre, so that it could drive back an approaching enemy by stakes and stones from the top. But when it was perceived that they had no other weapons but stakes, and because of their weight they could not throw them far from the wall, the order was given to approach, and to throw bundles of twigs and burning torches against the fort. And the troops quickly heaped them up.

16. The flame seizing the twigs around the wood, rose skyward and made them think that the whole mass had collapsed. But when the fire had burnt itself out and subsided. and the tower appeared again intact, Caesar was surprised and ordered the town to be surrounded by a rampart outside the range of their weapons. And so the townspeople were compelled by fear to surrender. The inquiry was made where the timber came from which was unscathed by the fire. Then they showed him the trees, of which there is an abundant supply in these parts. The fort was called Larignum following the name of the larch wood. Now this is brought down the Po to Ravenna; there are also supplies at the Colony of Fanum, at Pisaurum and Ancona and the municipia in that region. And if there were a provision for bringing this timber to Rome, there would be great advantages in building; and if such wood were used, not perhaps generally, but in the eaves round the building blocks, these buildings would be freed from the danger of fires spreading. For this timber can neither catch fire nor turn to charcoal, nor burn of itself.

17. Now these trees have leaves like those of the pine, the timber is tall, and for joinery work not less handy than deal. It has a liquid resin coloured like Attic honey. This is a cure for phthisical persons.

Larix vero, qui non est notus nisi is municipalibus qui sunt circa ripam fluminis Padi et litora maris Hadriani, non solum ab suco vehementi amaritate ab carie aut tinea non nocetur, sed etiam flammam ex igni non recipit, nec ipse per se potest ardere, nisi uti saxum in fornace ad calcem coquendam aliis lignis uratur; nec tamen tunc flammam recipit nec carbonem remittit, sed longo spatio tarde comburitur. Quod est minima ignis et aeris e principiis temperatura, umore autem et terreno est spisse solidata, non habet spatia foraminum, qua possit ignis penetrare, reicitque eius vim nec patitur ab eo sibi cito noceri, propterque pondus ab aqua non sustinetur, sed cum portatur, aut in navibus aut supra abiegnas rates conlocatur.

Ea autem materies quemadmodum sit inventa, est causa cognoscere. Divus Caesar cum exercitum habuisset circa Alpes imperavissetque municipiis praestare commeatus, ibique esset castellum munitum, quod vocaretur Larignum, tunc, qui in eo fuerunt, naturali munitione confisi noluerunt imperio parere. Itaque imperator copias iussit admoveri. erat autem ante eius castelli portam turris ex hac materia alternis trabibus transversis uti pyra inter se composita alte, uti posset de summo sudibus et lapidibus accedentes repellere. Tunc vero cum animadversum est alia eos tela praeter sudes non habere neque posse longius a muro propter pondus iaculari, imperatum est fasciculos ex virgis alligatos et faces ardentes ad eam munitionem accedentes mittere. Itaque celeriter milites congesserunt. Posteaquam flamma circa illam materiam virgas comprehendisset, ad caelum sublata efficit opinionem, uti videretur iam tota moles concidisse. Cum autem ea per se extincta esset et re quieta turris intacta apparuisset, admirans Caesar iussit extra telorum missionem eos circumvallari. Itaque timore coacti oppidani cum se dedidissent, quaesitum, unde essent ea ligna quae ab igni non laederentur. Tunc ei demonstraverunt eas arbores, quarum in his locis maximae sunt copiae. Et ideo id castellum Larignum, item materies larigna est appellata. Haec autem per Padum Ravennam deportatur. In colonia Fanestri, Pisauri, Anconae reliquisque, quae sunt in ea regione, municipiis praebetur. Cuius materies si esset facultas adportationibus ad urbem, maximae haberentur in aedificiis utilitates, et si non in omne, certe tabulae in subgrundiis circum insulas si essent ex ea conlocatae, ab traiectionibus incendiorum aedificia periculo liberarentur, quod ea neque flammam nec carbonem possunt recipere nec facere per se. Sunt autem eae arbores foliis similibus pini; materies earum prolixa, tractabilis ad intestinum opus non minus quam sappinea, habetque resinam liquidam mellis Attici colore, quae etiam medetur phthisicis.

Huys: A doore; Looke Huis.

Huis: A doore.

Ambrum (Rab) Seeke Lambrum.

Lambrum: wainscot, seeting

The eaue of a house; the brow, or coping of a wall, serving to keepe, or cast off the raine; also, a loope-hole, or small hole in a wall to giue light; also, the eye-veine, or veine thats next to the eye of a horse.

Ce sont les petites corniches qui sont au haut de toît, et qui préservent les murs de la chute des eaux. Ce mot est dérivé de larme, comme gouttière de goutte.

Ce mot, que nous n’avons trouvé nulle part, doit venir, ainsi que lambris, du latin imbrex, tuile creuse qui sert de faîtière ou de goutière; et ce doit être d’ambrun ou embrun qu’on a fait embruncher, dans le sens d’imbricare, s’il ne vient pas immédiatement de ce mot latin. L’embrun et lambris ne diffèrent qu’en ce que l’article est contracté dans lambris, et qu’il ne l’est pas dans l’embrun.

Toiture.

Ambrun, voir Embron

Embron, voir Embronc.

Embronc: adj., courbé, baissé, penché.

Embrun. Revêtement (à rapprocher de embruncher, l., I, ch. LIII, n. 26). Cf. Sainéan, t. I, p. 35.

Saillie de la corniche où passe la gouttière.

«Embroncher», c’est recouvrir de tuiles ou d’ardoises; l’«ambrun» est la couverture qui en résulte.

Original French: & d’autant plus que Pantagruel d’icelluy voulut eſtre faictz

Modern French: & d’autant plus que Pantagruel d’icelluy voulut estre facitz

See Pantagruel.

Original French: & ſeroit digne en ceſte qualité d’eſtre on degré mis de vray Pantagruelion,

Modern French: & seroit digne en ceste qualité d’estre on degré mis de vray Pantagruelion,

See Pantagruelion.

Original French: lequel de ſoy ne faict feu, flambe, ne charbon:

Modern French: lequel de soy ne faict feu, flambe, ne charbon:

Properties of larch.

«Nec ardet, nec carbonem facit», dit du mélèze Ravisius Textor (Officina, «Arbores diuersæ»), après Pline, XVI, 10.

Omnia autem haec genera accensa fuligine inmodica carbonbe repente expuunt cum eruptionis crepitu eiaculanturque longe excepta larice quae nec ardet nec carbonem facit nec alio modo ignis vi consumitur quam lapides.

All these [resinous] kinds of trees when set fire to make an enormous quantity of sooty smoke and suddenly with an explosive crackle send out a splutter of charcoal and shoot it to a considerable distance—excepting the larch, which does not burn nor yet make charcoal, nor waste away from the action of fire any more than do stones

Original French: Et par leur recit congneut Cæſar l’admirable nature de ce boys,

Modern French: Et par leur récit congneut Caesar l’admirable nature de ce boys,