Among plants named by metamorphosis of men or women.

Notes

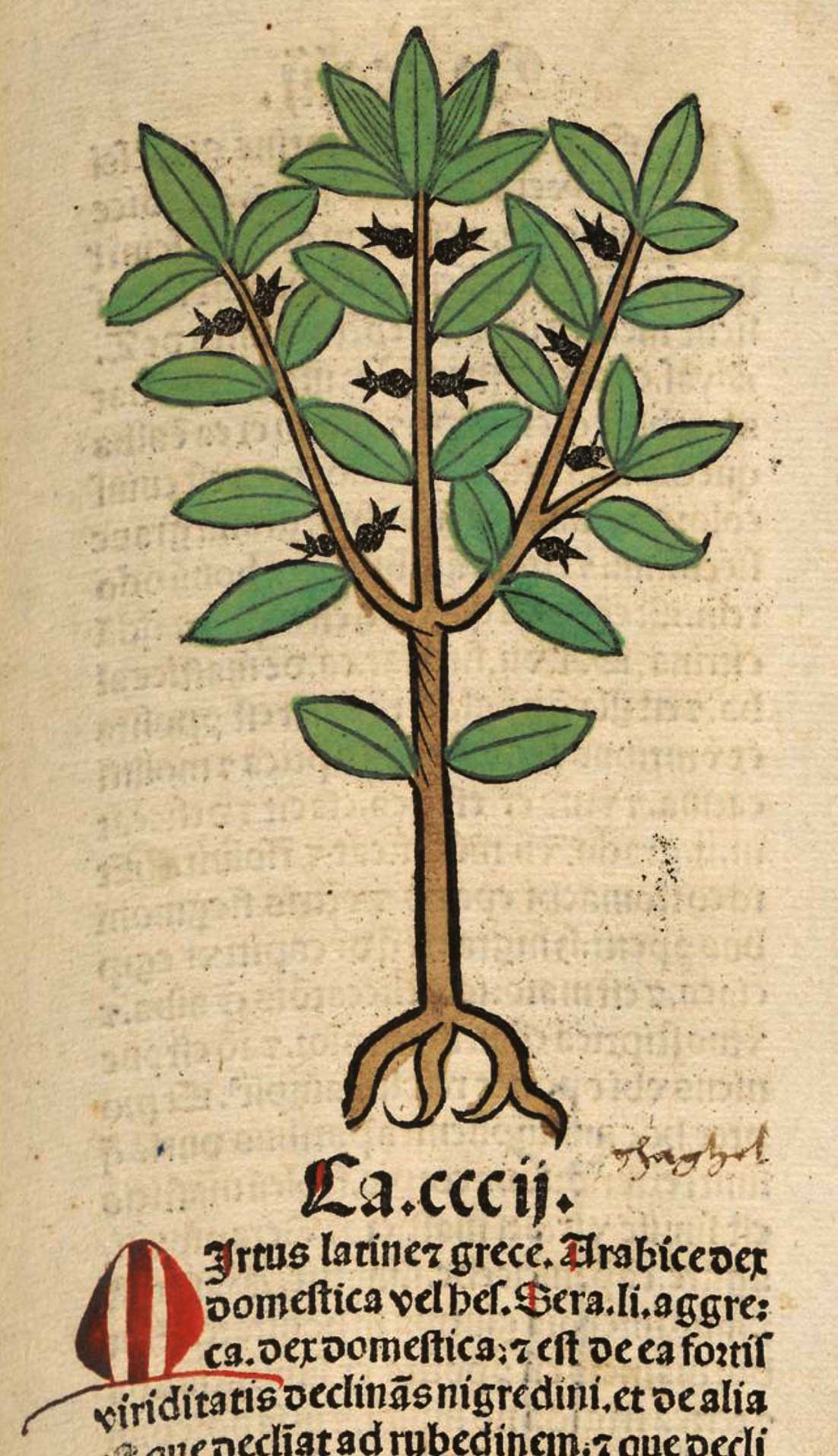

Mirtus

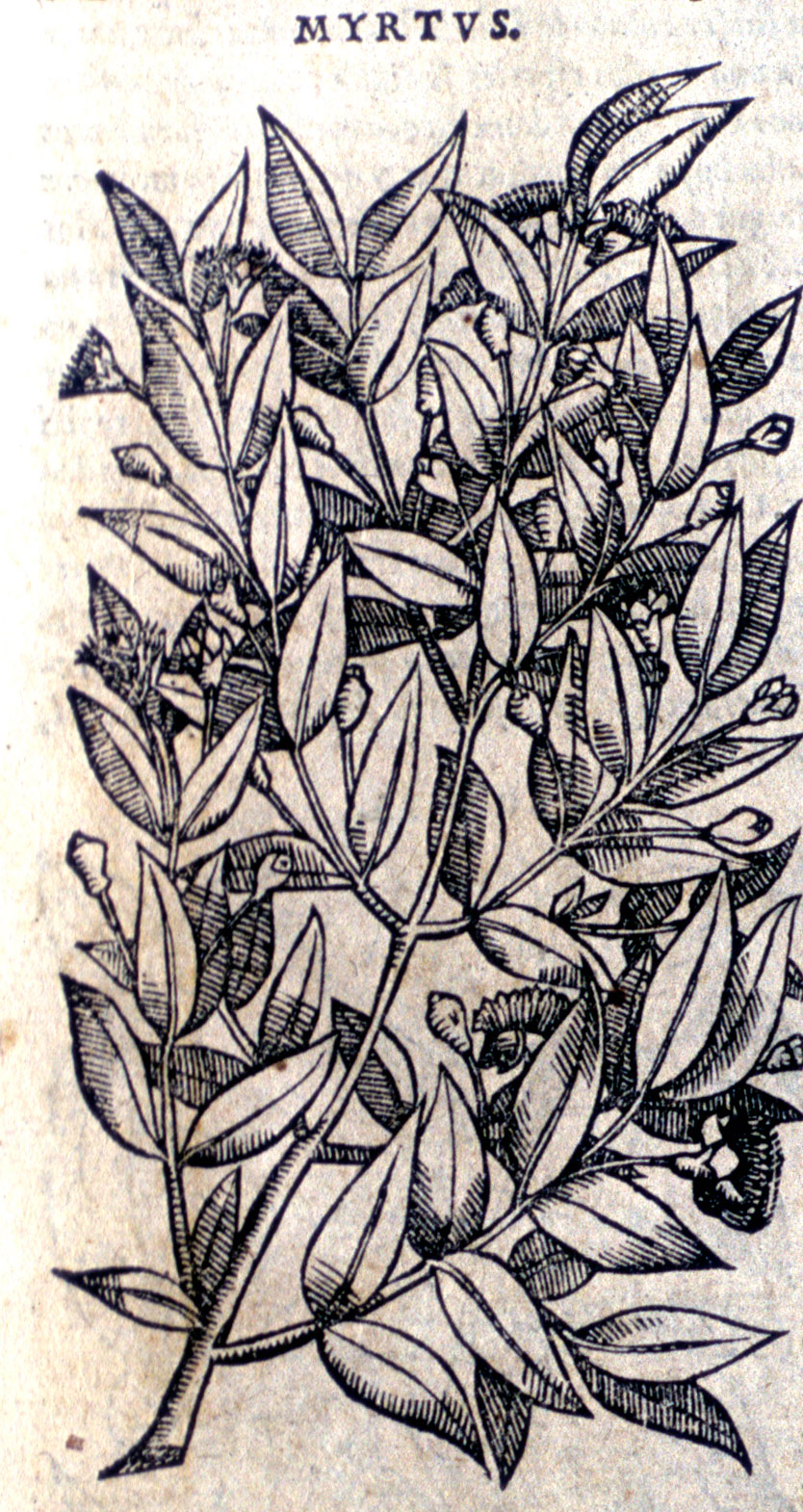

myrtus

myrtle

298. “Cinyras was her [Paphos’] son and, had he been without offspring, might have been counted fortunate. A horrible tale I have to tell. Far hence be daughters, far hence, fathers; or, if your minds find pleasure in my songs, do not give credence to this story, and believe that it never happened; or, if you do believe it, believe also in the punishment of the deed. If, however, nature allows a crime like this to show itself, [I congratulate the Ismarian people, and this our city;] I congratulate this land on being far away from those regions where such iniquity is possible. Let the land of Panchaia be rich in balsam, let it bear its cinnamon, its costum, its frankincense exuding from the trees, its flowers of many sorts, provided it bear its myrrh-tree, too: a new tree was not worth so great a price. Cupid himself avers that his weapons did not harm you, Myrrha, and clears his torches from that crime of yours. One of the three sisters with firebrand from the Styx and with swollen vipers blasted you. ’Tis a crime to hate one’s father, but such love as this is a greater crime than hate. …

331. yet they say that there are tribes among whom mother and son, daughter with father mates, and natural love is increased by the double bond. Oh, wretched me, that it was not my lot to be born there, and that I am thwarted by the mere accident of place!

470. “Forth from the chamber she went, full of her father, with crime conceived within her womb. The next night repeated their guilt, nor was that the end. At length Cinyras, eager to recognize his mistress after so many meetings, brought in a light and beheld his crime and his daughter. Speechless with woe, he snatched his bright sword from the sheath which hung near by. Myrrha fled and escaped death by grace of the shades of the dark night. Groping her way through the broad fields, she left palm-bearing Arabia and the Panchaean country; then, after nine months of wandering, in utter weariness she rested at last in the Sabaean land. And now she could scarce bear the burden of her womb. Not knowing what to pray for, and in a strait betwixt fear of death and weariness of life, she summed up her wishes in this prayer: ‘O gods, if any there be who will listen to my prayer, I do not refuse the dire punishment I have deserved; but lest, surviving, I offend the living, and, dying, I offend the dead, drive me from both realms; change me and refuse me both life and death!’ Some god did listen to her prayer; her last petition had its answering gods. For even as she spoke the earth closed over her legs; roots burst forth from her toes and stretched out on either side the supports of the high trunk; her bones gained strength, and, while the central pith remained the same, her blood changed to sap, her arms to long branches, her fingers to twigs, her skin to hard bark. And now the growing tree had closely bound her heavy womb, had buried her breast and was just covering her neck; but she could not endure the delay and, meeting the rising wood, she sank down and plunged her face in the bark. Though she has lost her old-time feelings with her body, still she weeps, and the warm drops trickle down from the tree. Even her tears have honour: and the myrrh which distils from the bark preserves the name of its mistress and will be remembered through all the ages

Myrrh

Smith translates as “Myrrh, from Myrsine” and cites Ovid Met. x. 298-514.

myrte, de myrsine

Le Myrtus des Anciens est notre M. communis L. (Myrtacée.) — M. Sainéan (H.N.R., 120) pense que cette Myrsine est Myrrha fille de Cinyre, roi de Chypre (Ovide, Mét., X, 298 et sqq.) qui fut changée en un arbre à myrrhe, que Rableais aurait confondu avec le myrte. (Paul Delaunay)

myrtle

Thus myrtle and myrrh tree after Myrsina or Myrrha, who was so changed because of her incestuous love of Cyniras, King of Cyprus, her father…

myrte, de Myrsine

Le myrtus est consacré à Vénus non pas à Myrsine. R. pense-t-il à Myrrha, métamorphosée en arbre à myrrhe? (EC).

Myrte

Confusion possible entre le myrte, consacré à Vénus et l’arbre à myrrhe.

Myrte

Le myrte est appelé en grec μνφτίνη et μνφφΐνη, à cause de Myrsine, jeune Athénienne, renommée pour sa beauté et sa force, et tuée par un jeune homme qu’elle avai devancé à la lutte et à la course. La légende est rapportée par les glossateurs de Dioscorides (I, corol. 157); voir Œuvres complètes, éd. Demerson, n. 34, p. 537.

myrtle

myrtle. Forms: mirtille, -ylle, mirt-, myrtel(l, -ylle, mirtle, mertle, mert-, mirt-, myrtil(l, myrtle. [adopted from Old French mirt-, myrtille, myrtle-berry, adaptation of popular Latin myrtilla, –us, diminutive of Latin myrta, myrtus myrt.]

The fruit or berry of the myrtle tree. Obsolete

C. 1400 Lanfranc’s Science of cirurgie 53 Poudre of mirtillis.

1526 Gt. Herbal cclxvii. (1529) P ij b, Mirte is a lytell tre so called, the whiche tre bereth a fruyte that is named Myrtylles.

1578 Henry Lyte, tr. Dodoens’ Niewe herball or historie of plantes 462 Barley giuen with Mirtels, or wine,… stoppeth the running of the belly.

1657 Coles Adam in E. lxxi. 135 Being boyled in red Wine with Pomegranat Rinds, and Myrtills, it stayeth the Lask.

A plant of the genus Myrtus (N.O. Myrtaceæ), esp. M. communis, the Common Myrtle, a shrub growing abundantly in Southern Europe, having shiny evergreen leaves and white sweet-scented flowers, and now used chiefly in perfumery. The myrtle was held sacred to Venus and is used as an emblem of love.

1562 William Turner A new herball, the seconde parte ii. 60 b, Dioscorides maketh ii. sortes of sowen or set myrtel trees… But other writers make yet mo kyndes of Myrtilles.

1590 Mary Herbert, Countess Pembroke The tragedie of Antonie 68 Since then the Baies so well thy forehead knewe To Venus mirtles yeelded haue their place.

1611 Bible Isaiah xli. 19, I will plant in the wildernes..the Myrtle, and the Oyle tree.

1639 S. Du Verger tr. Camus’ Admir. Events 14 The palmes of my valour, and mirtles of my incomparable love.

1667 John Milton Paradise Lost iv. 262 The fringed Bank with Myrtle crownd.

Myrrha

Myrrha (Greek: Μύρρα, Mýrra), also known as Smyrna (Greek: Σμύρνα, Smýrna), is the mother of Adonis in Greek mythology. She was transformed into a myrrh tree after having had intercourse with her father and given birth to Adonis as a tree. Although the tale of Adonis has Semitic roots, it is uncertain from where the myth of Myrrha emerged, though it was likely from Cyprus.

The myth details the incestuous relationship between Myrrha and her father, Cinyras. Myrrha falls in love with her father and tricks him into sexual intercourse. After discovering her identity, Cinyras draws his sword and pursues Myrrha. She flees across Arabia and, after nine months, turns to the gods for help. They take pity on her and transform her into a myrrh tree. While in plant form, Myrrha gives birth to Adonis. According to legend, the aromatic exudings of the myrrh tree are Myrrha’s tears.

Myrtus

Myrtus, with the common name myrtle, is a genus of flowering plants in the family Myrtaceae, described by Swedish botanist Linnaeus in 1753.

Over 600 names have been proposed in the genus, but nearly all have either been moved to other genera or been regarded as synonyms. The genus Myrtus has three species recognised today, including Myrtus communis, the “common myrtle”, is native across the Mediterranean region, Macaronesia, western Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. It is also cultivated.

The plant is an evergreen shrub or small tree, growing to 5 metres (16 ft) tall. The leaf is entire, 3–5 cm long, with a fragrant essential oil.

In Greek mythology and ritual the myrtle was sacred to the goddesses Aphrodite and also Demeter: Artemidorus asserts that in interpreting dreams “a myrtle garland signifies the same as an olive garland, except that it is especially auspicious for farmers because of Demeter and for women because of Aphrodite. For the plant is sacred to both goddesses. Pausanias explains that one of the Graces in the sanctuary at Elis holds a myrtle branch because “the rose and the myrtle are sacred to Aphrodite and connected with the story of Adonis, while the Graces are of all deities the nearest related to Aphrodite.” Myrtle is the garland of Iacchus, according to Aristophanes, and of the victors at the Theban Iolaea, held in honour of the Theban hero Iolaus.

In Rome, Virgil explains that “the poplar is most dear to Alcides, the vine to Bacchus, the myrtle to lovely Venus, and his own laurel to Phoebus.”At the Veneralia, women bathed wearing crowns woven of myrtle branches, and myrtle was used in wedding rituals. In the Aeneid, myrtle marks the grave of the murdered Polydorus in Thrace. Aeneus’ attempts to uproot the shrub cause the ground to bleed, and the voice of his dead brother warns him to leave. The spears which impaled Polydorus have been magically transformed into the myrtle which marks his grave

Myrrh

Myrrh (from Aramaic) is a natural gum or resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus Commiphora. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense, and medicine. Myrrh mixed with wine was common across ancient cultures, for general pleasure and as an analgesic.

The word myrrh corresponds with a common Semitic root m-r-r meaning “bitter”, as in Aramaic ܡܪܝܪܐ murr and Arabic مُرّ murr. Its name entered the English language from the Hebrew Bible, where it is called מור mor, and later as a Semitic loanword was used in the Greek myth of Myrrha, and later in the Septuagint; in the Ancient Greek language, the related word μῠ́ρον (múron) became a general term for perfume.