“Que grand tu as!” (“What a big one you’ve got!”) splurted Grandgousier at the sight of his new born son. Gargantua was delivered of his mother Gargamelle through her left ear after she stuffed herself on feast of tripes, as Alcofribas records in the sixth chapter of The Most Fearsome Life of the Great Gargantua, Father of Pantagruel.[1] The jolly company of feasters and tipplers declared that the boy must be named Gargantua, those being the first words his father spoke at his birth, after the fashion of the Hebrews. Gargantua’s own first words were, “Drink, drink, drink.” Cows in the number of 17,913 were required to keep him in milk. Motteux says that Gargantua’s great thirst, and the mighty drought that accompanied Pantagruel’s birth, were caused by the withholding of the cup from the laity and the clamor raised by the Reformers for the wine as well as the bread in the Eucharist.

Gargantua was transported to the Land of Fairies by Morgan la Fay, as were King Arthur, Enoch of Genesis, Elijah of Kings, and Ogier the Dane, Peer of France, who overcame Gargantua’s ancestor Bruyer.[2]

1. Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Gargantua. La Vie Inestimable du Grand Gargantua, Pere de Pantagruel, iadis composée par l’abstracteur de quinte essence. 1534. Ch. 6. Athena

2. Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Pantagruel. Les horribles et espouvantables faictz & prouesses du tresrenommé Pantagruel Roy des Dipsodes, filz du grand geant Gargantua, Composez nouvellement par maistre Alcofrybas Nasier. Lyon: Claude Nourry, 1532. Ch. 1. Athena

Notes

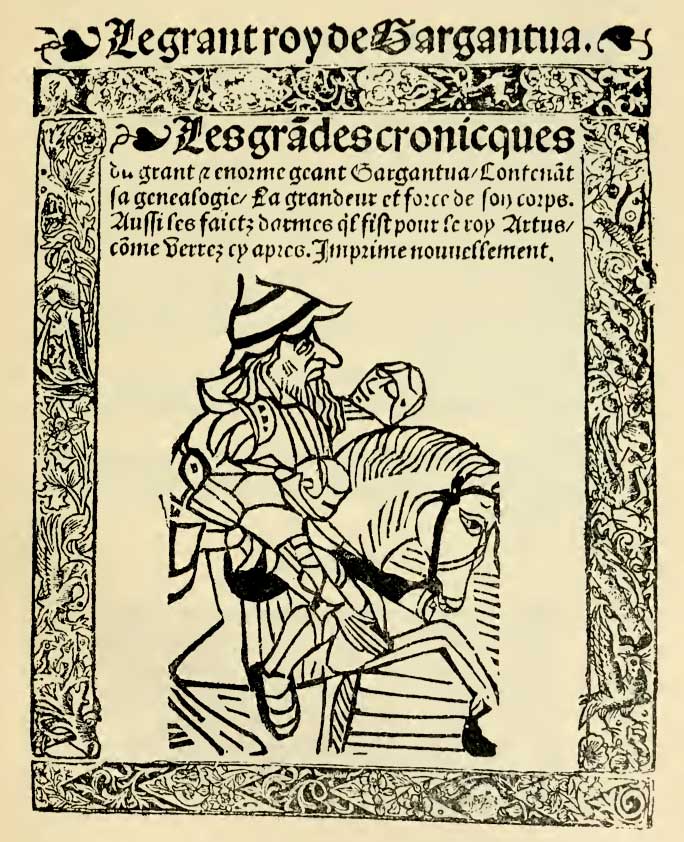

Gargantua

Le grant roy de Gargantua. Les grãdes cronicques du grant énorme géant Gargantua, Contenãt sa généalogie, La grandeur et force de son corps. Aussi les faictz darmes ql fist pour le roy Artus, come verrez cy apres. Imprime nouuellement.

Attributed to Rabelais. Undated, but presumably previous to the publication of Pantagruel in 1532. Only one copy known, at the Bibliothèque nationale de France [Bibl. Nat., Rés. Y2. 2127].

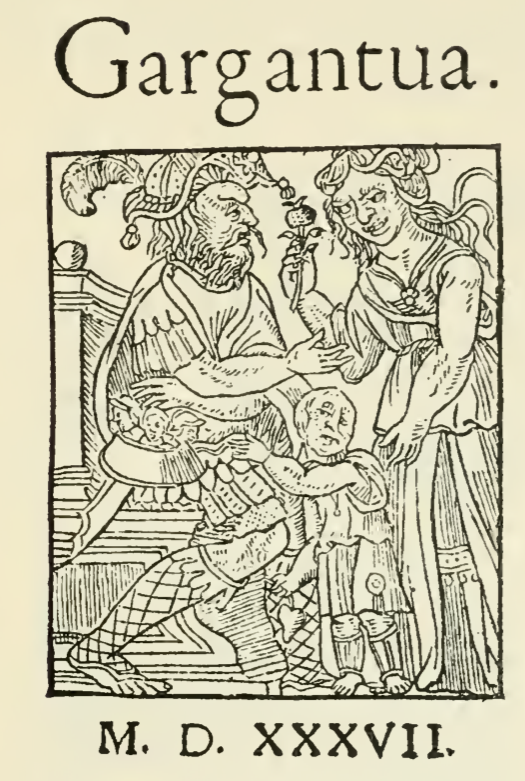

Gargantua

Title page from 1537 edition of Gargantua. Paris, Denis Janot?

De l’origine & antiquité du grand Pantagruel

Et le premier fut Chalbroth, qui engendra Sarabroth, qui engendra Faribroth, qui engendra Hurtaly, qui fut beau mangeur de souppes & regna au temps du deluge, qui engendra Nembroth, qui engendra Athlas qui avecques ses espaules guarda le ciel de tumber, qui engendra Goliath, qui engendra Eryx [lequel feut inventeur du ieu des gobeletz], qui engendra Titius, [qui engendra Eryon:] qui engendra Polyphemus, qui engendra Cacus [qui engendra Etion, lequel premier eut la verolle pour avoir dormi la gueule baye comme tesmoigne Bartachim], qui engendra Enceladus, qui engendra Ceus, qui engendra Typhoeus, qui engendra Aloeus, qui engendra Othus, qui engendra Aegeon, qui engendra Briareus qui avoit cent mains…

Gargantua

Chapitre. vi. Comment le nom fut imposé à Gargantua: et comment il humoyt le piot.

Le bonhomme Grantgousier beuvant, et se rigollant avecques les aultres entendit le cris horrible que son filz avoit faict entrant en lumière de ce monde, quand il brasmoit demandant à boyre/ à boyre/ à boyre/ dont il dist, que grant tu as, supple le gousier. Ce que oyans les assistans, dirent que vrayment il debvoit avoir par ce le nom Gargantua, puis que telle avoyt esté la première parole de son père à sa nativité, à l’imitation et exemple des anciens Hebreux. A quoy fut condescendu par icelluy, & pleut tresbien à sa mère. Et pour l’appaiser, luy donnèrent à boyre à tirelarigot, et feut porté sus les fonts, et là baptisé, comme est la coustume des bons christians. Et luy feurent ordonnées dix et sept mille neuf cens vaches de Pautille, et de Brehemond: pour l’alaicter ordinairement, car de trouver une nourrice convenente n’estoit possible en tout le pais, consideré la grande quantité, de laict requis pour icelluy alimenter. Combien qu’aulcuns docteurs Scotistes ayent affermé que sa mère l’alaicta, et qu’elle pouvoit trayre de ses mammelles quatorze cens pippes de laict pour chascune fois. Ce que n’est vraysemblable. Et a esté la proposition declarée par Sorbone scandaleuse, et des pitoyables aureilles offensive, et sentant de loing heresie. En cest estat passa iusques à un an et dix moys, en quel temps par le conseil des medicins on commencza le porter, & fut faicte une belle charrette à boeufz par l’invention de Iean Denyau, et là dedans on le pourmenoit par cy/ par là, ioyeusement & le faisoyt bon veoir car il portoit bonne troigne, et avoyt presque dix et huyt mentons: & ne cryoit que bien peu, mais il se couchioyt à toutes heures, car il estoit merveilleusement phlegmaticque des fesses, tant de sa complexion naturelle, que de la disposition accidentale qui luy estoit advenue par trop humer de purée Septembrale. Et n’en humoyt poinct sans cause. Car s’il advenoyt qu’il feut despit, courroussé, faché, ou marry, s’il trepignoyt/ s’il pleuroyt, s’il cryoit, luy aportant à boyre, l’on le remettoyt en nature, & soubdain demouroyt quoy et ioyeux. Une de ses gouvernantes m’a dict, que de ce fayre il estoyt tant coustumier, qu’au seul son des pinthes & flaccons, il entroyt en ecstase, comme s’il goustoyt les ioyes de paradis. En sorte qu’elles considerant ceste complexion divine pour le resiouyr au matin faisoyent davant luy donner des verres avecques un cousteau, ou des flaccons avecques leur toupon, ou des pinthes avecques leur couvercle. Auquel son il s’esguayoit, il tressailoit, & luy mesmes se bressoit en dodelinant de la teste, monichordisant des doigtz, & baritonant du cul.

Gargantua

Chapter VII. After what manner Gargantua had his name given him, and how he tippled, bibbed, and curried the can.

The good man Grangousier, drinking and making merry with the rest, heard the horrible noise which his son had made as he entered into the light of this world, when he cried out, Some drink, some drink, some drink; whereupon he said in French, Que grand tu as et souple le gousier! that is to say, How great and nimble a throat thou hast. Which the company hearing, said that verily the child ought to be called Gargantua; because it was the first word that after his birth his father had spoke, in imitation, and at the example of the ancient Hebrews; whereunto he condescended, and his mother was very well pleased therewith. In the meanwhile, to quiet the child, they gave him to drink a tirelaregot, that is, till his throat was like to crack with it; then was he carried to the font, and there baptized, according to the manner of good Christians.

Immediately thereafter were appointed for him seventeen thousand, nine hundred, and thirteen cows of the towns of Pautille and Brehemond, to furnish him with milk in ordinary, for it was impossible to find a nurse sufficient for him in all the country, considering the great quantity of milk that was requisite for his nourishment; although there were not wanting some doctors of the opinion of Scotus, who affirmed that his own mother gave him suck, and that she could draw out of her breasts one thousand, four hundred, two pipes, and nine pails of milk at every time.

Which indeed is not probable, and this point hath been found duggishly scandalous and offensive to tender ears, for that it savoured a little of heresy. Thus was he handled for one year and ten months; after which time, by the advice of physicians, they began to carry him, and then was made for him a fine little cart drawn with oxen, of the invention of Jan Denio, wherein they led him hither and thither with great joy; and he was worth the seeing, for he was a fine boy, had a burly physiognomy, and almost ten chins. He cried very little, but beshit himself every hour: for, to speak truly of him, he was wonderfully phlegmatic in his posteriors, both by reason of his natural complexion and the accidental disposition which had befallen him by his too much quaffing of the Septembral juice. Yet without a cause did not he sup one drop; for if he happened to be vexed, angry, displeased, or sorry, if he did fret, if he did weep, if he did cry, and what grievous quarter soever he kept, in bringing him some drink, he would be instantly pacified, reseated in his own temper, in a good humour again, and as still and quiet as ever. One of his governesses told me (swearing by her fig), how he was so accustomed to this kind of way, that, at the sound of pints and flagons, he would on a sudden fall into an ecstasy, as if he had then tasted of the joys of paradise; so that they, upon consideration of this, his divine complexion, would every morning, to cheer him up, play with a knife upon the glasses, on the bottles with their stopples, and on the pottle-pots with their lids and covers, at the sound whereof he became gay, did leap for joy, would loll and rock himself in the cradle, then nod with his head, monochordizing with his fingers, and barytonizing with his tail.

Gargantua

Clef des allégories du Roman de Rabelais. Donnée au XVIIe siècle. Cette clef ne mérite pas d’etre prise au sérieux. Elle peut cependant donner une idée des interprétations arbitraires dont le Roman de Rabelais a été l’object, et nous n’avons pas jugé inutile de la reproduire.

Gargantua = François Ier

Gargantua

Gargantua. A giant.

1571 Golding Calvin on Psalms lxxiii. 8 Gyantes, or one-eyed Gargantuas.

1579 Fulke Heskins’ Parl. 164 Now riseth vp this Gargantua, and will proue..that one bodie may be in another.

1598 B. Jonson Ev. Man in Hum. ii. i, I’ll go near to fill that huge tumbrel-slop of yours with somewhat, an I have good luck: your Garagantua breech cannot carry it away so.

1600 Shakespeare As You Like It. iii. ii. 238 You must borrow me Gargantuas mouth first.

1651 Randolph, etc. Hey for Honesty ii. v, Mine are all diminutives, Tom Thumbs; not one Colossus, not one Gargantua among them.

1593 Harvey Pierce’s Supererog. Wks. II. 224 Pore I… that am matched with such a Gargantuist, as can deuoure me quicke in a sallat.

1596 Nashe Haue with you Wks. (Grosart) III. 49 This Gargantuan bag-pudding.

1619 Purchas Microcosmus xxvii. 267 His Gargantuan bellyed-Doublet with huge huge sleeves.

1630 Randolph Panegyr. to Shirley’s Gratef. Serv. A iij, My ninth lasse affords No lycophronian buskins nor can straine Garagantuan lines to Gigantize thy veine.

1866 Carlyle Remin. (1881) I. 146 While his wild home-grown Gargantuisms went on.

1893 Curwen Hist. Booksellers 276 Bogue’s small venture stood a poor chance against enterprise of this gargantuan scale.

Hence gargantuan, enormous, monstrous; also as gargantuan-bellied.

1593 Harvey Pierce’s Supererog. Wks. II. 224 Pore I… that am matched with such a Gargantuist, as can deuoure me quicke in a sallat.

1596 Nashe Haue with you Wks. (Grosart) III. 49 This Gargantuan bag-pudding.

1619 Purchas Microcosmus xxvii. 267 His Gargantuan bellyed-Doublet with huge huge sleeves.

1630 Randolph Panegyr. to Shirley’s Gratef. Serv. A iij, My ninth lasse affords No lycophronian buskins nor can straine Garagantuan lines to Gigantize thy veine.

1866 Carlyle Remin. (1881) I. 146 While his wild home-grown Gargantuisms went on.

1893 Curwen Hist. Booksellers 276 Bogue’s small venture stood a poor chance against enterprise of this gargantuan scale.

Gargantua

Out of nowhere Gargantua stepped smack into a convocation at Pantagruel’s castle, as you would have guessed, in time for dessert. Moments earlier one of the serving girls, after stashing the bundle of kindling she had picked up from the woodpile on the path to the privy, had whispered to Panurge, “Keep your fork, Duke, the pie’s coming.” As Panurge parted his lips to respond, Pantagruel spotted Gargantua’s dog Kyne and commanded, “All stand for the King.” Gargantua begged the crowd to do him the favor of not leaving their seats or interrupting their discourse, and in compliance, discussion continued on a question posed by Panurge—should he marry, or should he not.

The philosopher Trouillogan had offered two pieces of advice: “Both the two together,” and “Neither the one, nor the other.” Gargantua chimed in that the answer “is like the one given by an ancient philosopher, when asked whether he had a certain woman as his wife. ‘I’ve had her,’ he answered, ‘but she hasn’t got me. I possess her, but I’m not possessed by her.’” Pantagruel smiled. “A similar answer was made by a Spartan wench when she was asked whether she had ever fucked a man,” he said. “She answered, ‘Never, but they sometimes fuck me.’” See also on this intercourse, the Apothegms of Erasmus of Rotterdam, and Book Three, 49.11

“That same wench,” said Garganuta, “if I be not mistaken, used to fill her mouth full of wheat and run around the neighborhood, listening at doors. If a boy’s name was mentioned, it was he who was to be her husband.”

“Yes,” said Epistemon, “She would buy a penny’s worth of pins, stick nine into an apple, throw the tenth away, and put the apple in her left stocking. She tied the stocking with her right garter and then went to bed, hoping to dream of her future husband. On Halloween she would go into a strange garden and steal a head of cabbage. She would take the cabbage into a field, find a dunghill, and standing on it and eating the cabbage, would look into a mirror, hoping for a glimpse of her future husband.”

“But the Fates were cruel to her in the end,” said Pantagruel. “When she was groping, blindfolded, for her wedding ring, the children tricked her into dipping her hand in a bowl of clay.”

Panurge then said that the mention of a wedding ring put him in mind of the story of Hans Carvel, which he would relate in its proper time, and also of an affair he had lately had with a lady in Paris. Although pressed to tell this story, he would only say, “The whole shooting match was a pain in the butt. I’m glad it’s behind me now.”